WELCOME to Camp Low ’n’ Slow

NC State magazine’s Senior Associate Editor Bill Krueger is set to retire in June. So we pulled out one of our favorite features he did, a 2017 profile of the NC State BBQ Camp. Photography by Ted Richardson.

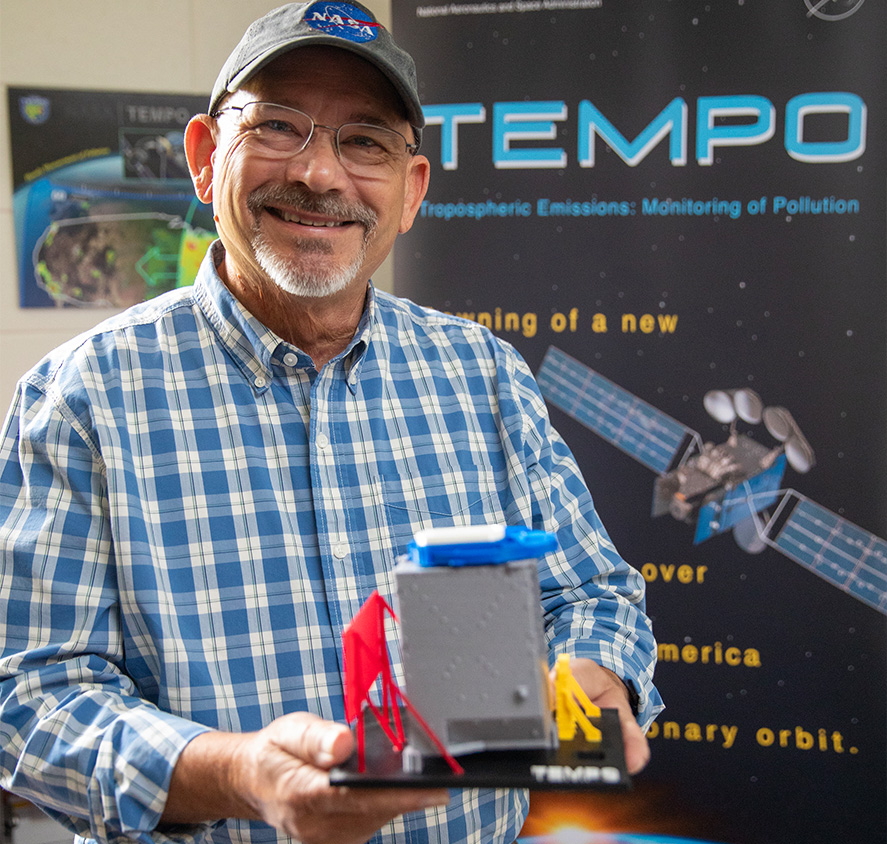

Dana Hanson is wearing a necklace adorned with plastic pigs. He claims to have lost track of how many smokers and grills he has at home. And one of his favorite childhood memories was seeing a lamb butchered on his family’s farm in Wisconsin. “All the biology,” he says, “it kind of was right there.”

So it’s no surprise that Hanson calls himself a “meat dork.” As an associate professor of food science at NC State, Hanson helps meat producers throughout North Carolina stay current on the latest rules, regulations, technology and industry practices. He also is charged with engaging the public on issues such as food safety and preparation, which is why he is standing in front of 30 men in a classroom in Schaub Hall. With a string of plastic pigs dangling across his chest.

The men are here for the NC State BBQ Camp, an annual event that offers a blend of science, hands-on food preparation and cultural history. They are wearing shorts, T-shirts and ball caps, not unlike the kids at various camps that spread across NC State’s campus each summer. In the real world, though, the big kids at the BBQ Camp have serious jobs as lawyers, salesmen, financial advisers, professors and IT security specialists.

What these men, ranging in age from their late 20s to late 60s, have in common is their love of barbecue. Hanson, who serves as the camp director, is among his people here. When they talk about the first time they smoked, they aren’t referring to cigarettes (or something more clandestine). Some of their introductions include a mention of favorite barbecue restaurants (from Wilber’s Barbecue in Goldsboro, N.C., to Red Bridges Barbecue Lodge in Shelby, N.C.), often as a way of letting others know what part of the state they’re from. When they mention bark, they aren’t talking about dogs or trees, but rather the spicy, sweet crust that forms on the edges of smoked meat.

“We will feed you well. Your caloric intake . . . your curve is going to spike.”

— Dana Hanson

That’s why they have each paid $450 for a two-day camp on the science of cutting, seasoning and smoking meat. “They’re with a bunch of people of their same kind,” says Hanson. “They just eat, live and breathe it.”

They will certainly do that over the course of the next two days, as Hanson makes clear when he kicks off the camp. “We will feed you well,” he says. “Your caloric intake . . . your curve is going to spike.”

TAKING THEIR TIME

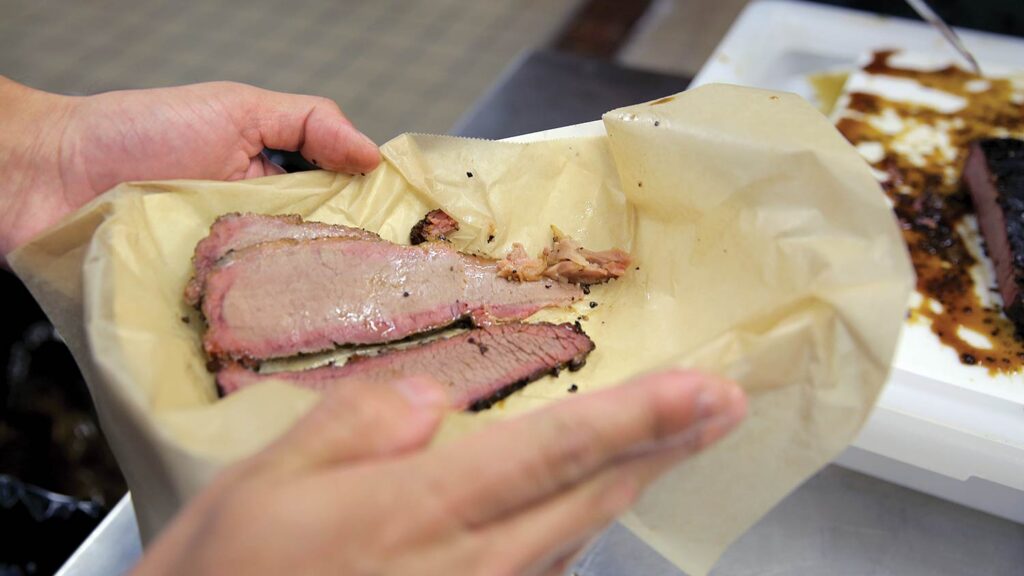

Outside, an industrial smoker is loaded with beef briskets that have been on the grill for several hours. The smoky smell washes over the campers, and they waste no time pulling out their phones to take pictures. Hanson explains that the butcher’s paper that wraps the briskets keeps the meat from getting too black and crispy during the long hours it is in the smoker. One camper asks about using foil — the “Texas crutch,” as they call it in barbecue circles — instead. “It steams the brisket,” Hanson says. “If you don’t want pot roast, don’t use foil.”

Other questions range from target temperatures for the meat to what sort of spices work well on brisket. “For me, on brisket, it’s salt and pepper and let it ride,” says Hanson, who once spent three days at a barbecue camp at Texas A&M devoted solely to beef brisket. “It doesn’t need rubs or sauces.”

“For me, on brisket, it’s salt and pepper and let it ride. It doesn’t need rubs or sauces.”

— Dana Hanson

Hanson is a mountain of a man, a former offensive lineman for the South Dakota State Jackrabbits who grew up on the brats of Wisconsin. When he realized in college that he wasn’t going to make a living playing football, he turned to food science. When Hanson arrived at NC State 15 years ago, though, he realized he still had a thing or two to learn about meat. He was clueless when one of his new colleagues invited him to a “pig pickin’,” and was blown away when he saw all the pig cookers blowing smoke outside of Carter-Finley Stadium before his first Wolfpack football game. “Yeah, my learning curve was pretty steep when I found out that pig pickin’ was a religion around here,” he says. “But, I thought, ‘I’m in a good place for barbecue.’”

Barbecue can mean different things to different people. Some campers prefer the pulled pork of North Carolina while others favor the beef brisket of Texas or Memphis’ dry-rub ribs. Some swear by the vinegar-based sauce of eastern North Carolina while others pledge their allegiance to the ketchup-based sauce they grew up eating in the western part of the state. A few even have kind words for the mustard-based sauce of South Carolina or the mayonnaise-based white barbecue sauce found in Alabama.

But no matter the meat or the sauce, all of the men at the camp relish the fact that it takes hours to achieve the smoky splendor found in the best barbecue. That’s time that can be spent visiting with family and friends, enjoying a few beers, and taking a step off the treadmill of life. For them, the formula for success can be boiled down to three simple words — low and slow (as in temperature and time). “There is just something enjoyable about spending 12 to 24 hours preparing a meat and then serving it at a cookout,” says Whitfield Gibson, a 34-year-old lawyer who had his wedding rehearsal dinner at The Pit barbecue restaurant in downtown Raleigh. “It is both a sense of accomplishment and fulfillment. And if you get some compliments along the way, all the better.”

Or, as Charley Warner ’89, a bank operations executive from Charlotte, N.C., who helps prepare as much as 12,000 pounds of pork barbecue for a regional Boy Scout gathering each year, says, “Faster is not better.”

THERE’S THE RUB

The lessons at camp range from how to identify the different cuts of meat in a hog to tips for making a great rub for ribs or other meats. Campers are required to wear lab coats and hair nets when their work takes them into the meat lab, a room filled with stainless steel tables, meat cleavers, freezers and industrial meat grinders. With the room chilled to 38 degrees, campers can see Hanson’s breath as he tells them the keys to making good sausage. “You want to create a bind that springs against your teeth when we bite into it,” he says. “The salt does the binding. Without salt, this is ground beef.” Later, while demonstrating how to trim the fat off a “packer cut” brisket, Hanson offers another tip — if you want beef ribs, be sure to ask for “beef flanken” ribs because they have much more meat.

Hanson also gives the campers a chance for some hands-on training and spirited competition when he divides them into six groups and challenges them to come up with their own rub to be used on pork ribs. The campers will determine a winner by a taste test. Hanson and Eddie Wilson, director of culinary innovation at Golden Corral and a former executive chef at Talley Student Union, offer more tips: coriander and paprika work well in rubs (but steer clear of smoked paprika), kosher or sea salt is preferable because it melts and absorbs into the meat faster than table salt, garlic works better than garlic salt, and spices and woods aren’t mutually exclusive. “If you use cherry wood, you might try a cinnamon spice,” Wilson tells the campers.

Many of the campers have their own ideas. Scott Hughes ’89, a financial adviser from Charlotte, N.C., has a recipe for a rub that he gives out to friends as Christmas gifts. Jim Holloway, 59, a real estate appraiser from Raleigh, is trying to convince his group to use some New Mexico chiles that he brought with him for the contest. “I’m competitive,” he confesses. Other groups are considering using ancho chiles, onion powder and ginger.

Holloway’s group is happy with their creation. “It’s got a nice bite to it,” says Tim Jones, 59, who manages a heating and air wholesale branch office in Durham, N.C., and has dreams of owning his own food truck. “I can taste a little bit of everything in there.” After one of the campers takes a photo, Holloway declares, “We’re ready to take it to market.”

A SIDE OF HISTORY

Dinner that first night is a feast of meat. Each camper is expected to try three grades of brisket — a lesson in the relative value of different grades of meat — the sausage they made earlier in the day and some smoked turkey. Even the macaroni and cheese has bits of ham in it. “I hope you all have your cardiologists on speed dial,” Hanson says. “You might need it.”

“I hope you all have your cardiologists on speed dial. You might need it.”

— Dana Hanson

The second day starts with more meat: sausage biscuits for breakfast. Then it’s back to the meat lab, where everyone will be challenged to trim pork spare ribs. Hanson shows them how to remove the membrane that runs along the bone side and how to use their fingers to scrape out much of what is known as leaf fat. He gives each group 20 minutes to prepare four racks of rib. “My, my, that looks good,” Hughes says as he pulls the membrane off a rack.

When the ribs are rubbed and ready for the smoker, one group poses for pictures with their entry. “This is going to be interesting,” one of the campers says as 24 large racks of ribs — nearly one per camper — are jammed into the smoker. “Yeah, especially around midnight when it starts talking to me,” says another, mindful of the potential aftershock of all the meat they are consuming. “I’m taking more pictures of this than I did when my daughter was born,” one of the campers says.

“I’m taking more pictures of this than I did when my daughter was born.”

— Camp participant

At lunch, each camper samples at least six ribs—one from each group—as well as some marinated turkey and another turkey with a salt-and-pepper rub. “Oh, my god, I may never eat again,” one camper says as he surveys the pile of charred meat on his plate. Later, when the votes are cast with a haphazard show of hands, Hanson declares it a six-way tie. Everyone is a winner at BBQ Camp.

For many of the men here, barbecue provides a connection to their past, evoking memories of watching their dads, uncles and granddads swap stories around the pit or smoker. “I grew up in Oxford, North Carolina, working in the tobacco fields,” says Hughes. “There was always somebody doing a whole hog. My connection with barbecue is as natural as my North Carolina heritage.”

It is a history that is as old as the nation. John Shelton Reed, a retired sociology professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, the author of a book on barbecue and a founder of a group dedicated to “true barbecue” prepared over a wood fire, tells the campers that George Washington wrote about going to barbecues and that the governor of Oklahoma, in 1923, hosted a barbecue for 100,000 people. He recalls the rather unsavory story of William Byrd II, a Virginia aristocrat who helped draw the state lines between Virginia and North Carolina. After visiting North Carolina in 1726, Byrd said the state was populated by “porcivorous” people who eat so much pork that many of them “seem to grunt rather than speak in their ordinary conversation.”

At this point in history, the NC State BBQ Camp is a stand against a fast-food world. We can order breakfast, lunch or dinner from our car and have it waiting when we drive around to the other side of the building. We can have a fully cooked pizza, not to mention concoctions like stuffed cheesy bread, delivered to our house. Or we can grab something out of the fridge and “nuke it” for a few minutes in the microwave. Just like that, dinner is served.

Not here, not at Camp Low ’n’ Slow, where campers take their time to savor the preparation, taste and conversation about barbecue. Even if it comes, with no apologies to William Byrd, in a hum of satisfied grunts.

- Categories: