The Vibe is Alive at 75

College of Design’s founders left a lasting legacy of Modernism.

By J. Michael Welton

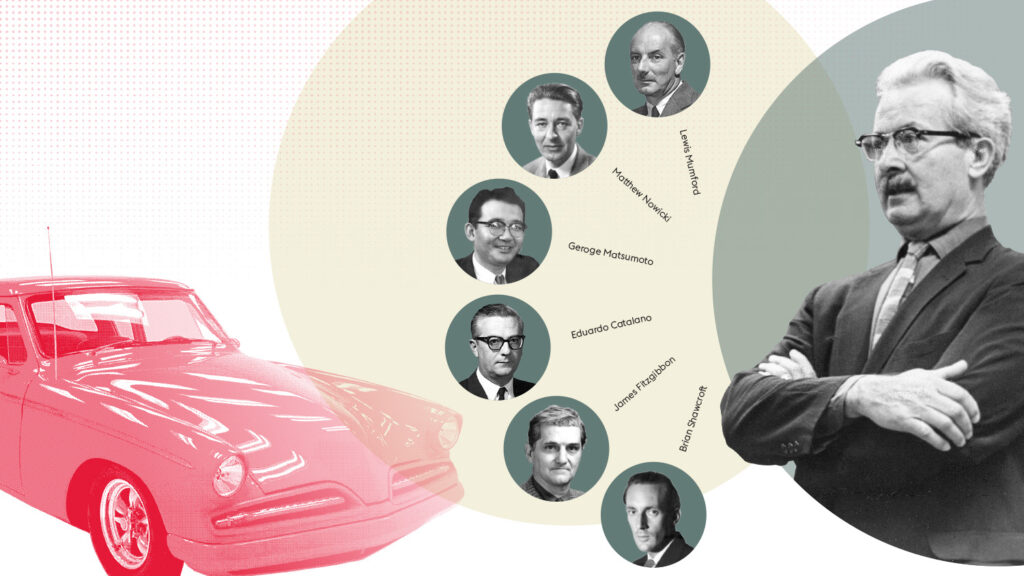

In the fall of 1960, Henry Kamphoefner, dean of the NC State School of Design, pulled up to Raleigh’s downtown bus station to pick up Brian Shawcroft, a recent MIT grad, for a faculty interview. He was driving a bright red 1953 Studebaker, stripped of its bumpers and chrome. The iconic car already was hailed as the epitome of modern design. But Kamphoefner had kicked it up a notch by removing its ornament. Modernism, after all, eschews decoration.

This year, as the College of Design celebrates its 75th anniversary, the legacy of Kamphoefner and his embrace of Modernism in those early years lives on. NC State faculty and graduates have left a lasting impact on the built environment in the Triangle and beyond, represented by such structures as Dorton Arena at the N.C. State Fairgrounds, the Denver International Airport and the Smithsonian’s Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

The mantra of Modernism is that “form follows function.” In architecture, that means clean lines, flat roofs, deep overhangs, open floor plans and glass curtain walls — and abolishing the froufrou and ornate decoration found in Victorian, Colonial and Georgian Revival styles.

The mantra of Modernism is that “form follows function.” In architecture, that means clean lines, flat roofs, deep overhangs, open floor plans and glass curtain walls . . .

In the Triangle alone there are at least 800 Modernist homes, according to George Smart, CEO of US Modernist, most designed by NC State architects. That’s in part because Kamphoefner hired internationally known architects to be part of the founding faculty, and he insisted that his professors build as well as teach. This was a school where the practice of architecture mattered. Besides, how better to preach the doctrine of Modernism than to build it?

Kamphoefner was offered the position of dean — and a salary of $9,000 — by Chancellor J.W. Harrelson in 1947. At the time he was acting head of the School of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma. When he arrived in Raleigh to meet Harrelson, he was armed with four non-negotiable conditions: The current department head had to return to teaching, replaced by “a man of national reputation.” One tenured professor must resign. Five non-tenured instructors were to be terminated and replaced by six others. And there had to be a space on campus dedicated to the new school.

The chancellor agreed to all. Classes at the new School of Design commenced in the fall of 1948. Kamphoefner brought with him four widely known Modernists and set about to making Raleigh a center of the movement. He enlisted Lewis Mumford, architecture critic at The New Yorker, to come and help shape the curriculum. Buckminster Fuller, who developed the geodesic dome, was a visiting lecturer who worked hands-on with students. And Frank Lloyd Wright came to deliver a lecture at Reynolds Coliseum in 1950, attracting a crowd of 5,000.

. . . Kamphoefner brought well-known practitioners “to this little red-dirt town of 50,000 people.”

– Frank Harmon

Left: Henry Kamphoefner and Frank Lloyd Wright walk NC State’s campus on his visit in 1950. Above: Architecture students work with Buckminister Fuller on a design for a cotton mill housed in a geodesic dome. Photographs courtesy of Special Collections, NC State University Libraries

“He was brilliant,” says Raleigh author, professor and architect Frank Harmon, noting that Kamphoefner brought well-known practitioners “to this little red-dirt town of 50,000 people.” At that time, he says, Raleigh “was the center of the architecture world.”

It was Mumford who encouraged Kamphoefner to hire Polish architect Matthew Nowicki as head of the architecture department. And after Kamphoefner asked him to build as well as teach, Nowicki designed the groundbreaking Dorton Arena in 1948. When the arena opened in 1952, with its distinctive saddle-shaped roof supported by torqued steel cables, it was hailed as the greatest building of its time. Architectural Record named it one of the most significant of the last century. (Nowicki would not live to see it built; he was killed in a 1950 plane crash, and the arena was completed by Raleigh architect William Deitrick.)

While Dorton was under construction, German-born Modernist Mies van der Rohe, regarded as one of the pioneers of Modernism, came to see it from Chicago, where he was director of the department of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology. In a visit with students at a second-story Hillsborough Street apartment, legend has it that he imbibed so much that when he left, he fell down a series of steps. Worried that they’d killed the architectural titan, the students breathed a sigh of relief when he stood up and walked away.

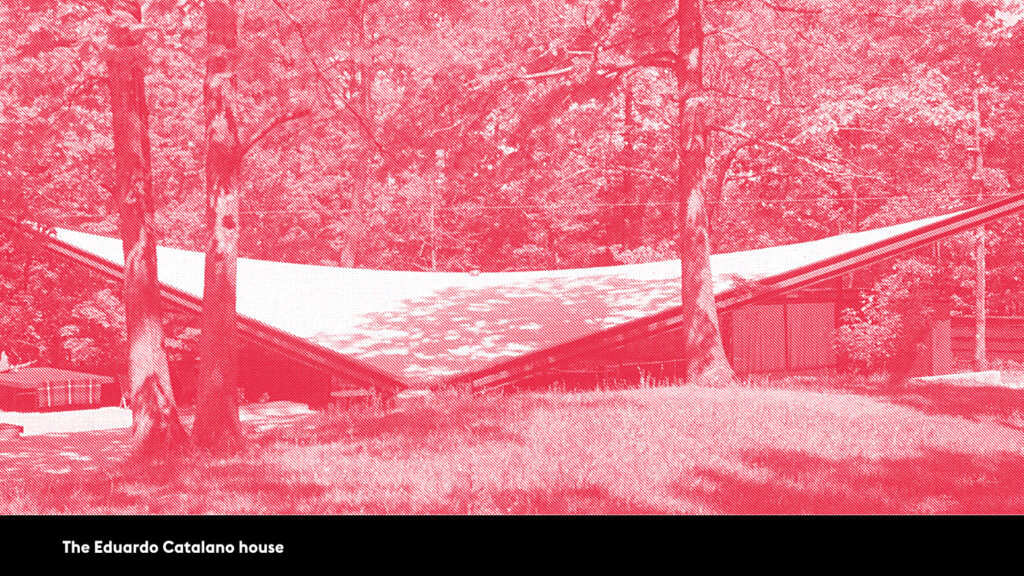

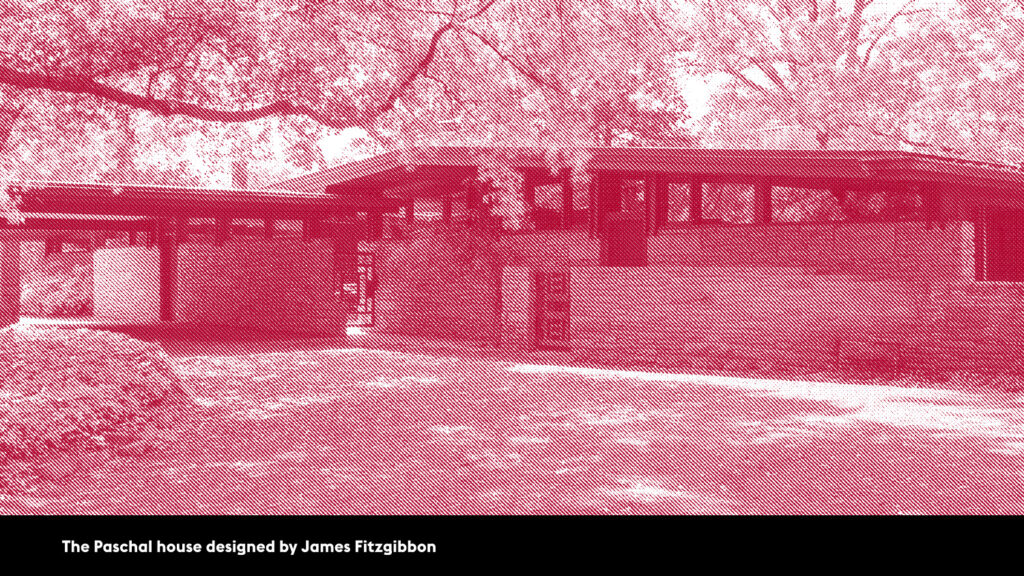

In the 1950s, Harmon says, “every critic knew about the place.” One reason was that the faculty was building some of the nation’s most innovative residences. James Fitzgibbon designed what was known as the Paschal House in Raleigh in 1950, using stone walls, deep overhangs and glass expanses. (Despite efforts to preserve it, the house was torn down in 2013.) After Argentine expat Eduardo Catalano, then teaching at London’s Architectural Association, came to NC State, he designed the eye-popping Catalano House. A 1,700-square-foot glass box, it was sheltered by a 3,600-square-foot hyperbolic paraboloid roof. It was named “House of the Decade” by House and Home magazine. (The house was torn down in 2001.)

The same year, George Matsumoto, another founding faculty member, created his own Raleigh home. Designed around four-by-eight-foot modules of Masonite panels, it was one of 20 he built here, many of which are still standing. “They’re as modern and Avant Garde today as when they were built in the 1950s,” says Turan Duda ’76, partner in the Durham firm that bears his name.

Kamphoefner, who retired in 1972, lived in a house that he and Matsumoto designed, where he frequently hosted well-known architects. When he arrived with Shawcroft and his wife in 1960, he showed the couple two rooms, each with a single bed. He pointed to one, saying that Frank Lloyd Wright had slept there. Mies had slept in the other. “You have to choose,” he told Shawcroft.

The British-born Shawcroft — who would go on to design nearly two dozen Modernist houses in the Raleigh area in coming decades — chose Wright. His wife would sleep where Mies once had.

J. Michael Welton is an architecture writer and the author of Drawing from Practice: Architects and the Meaning of Freehand.

Notable College of Design Alumni

Dick Bell ’50, designer of Raleigh’s Pullen Park and the Brickyard

Ronald Mace ’66, architect and creator of the concept of Universal Design, which ensures accessibility in public spaces

Richard Curtis ’72, one of the founding visual editors of USA Today

Curtis Fentress ’72, designer of Denver International Airport

Phil Freelon ’75, architect of record of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Brian Leonard ’89, ’91, vice president of design at Lenovo

Kim Tanzer ’83 MARCH, former dean of architecture at the University of Virginia

Turan Duda ’76, designed the Winter Garden at the World Financial Center in New York City and NC State’s Talley Student Union

For the full College of Design timeline, go to