In the Shadow of the Bomb

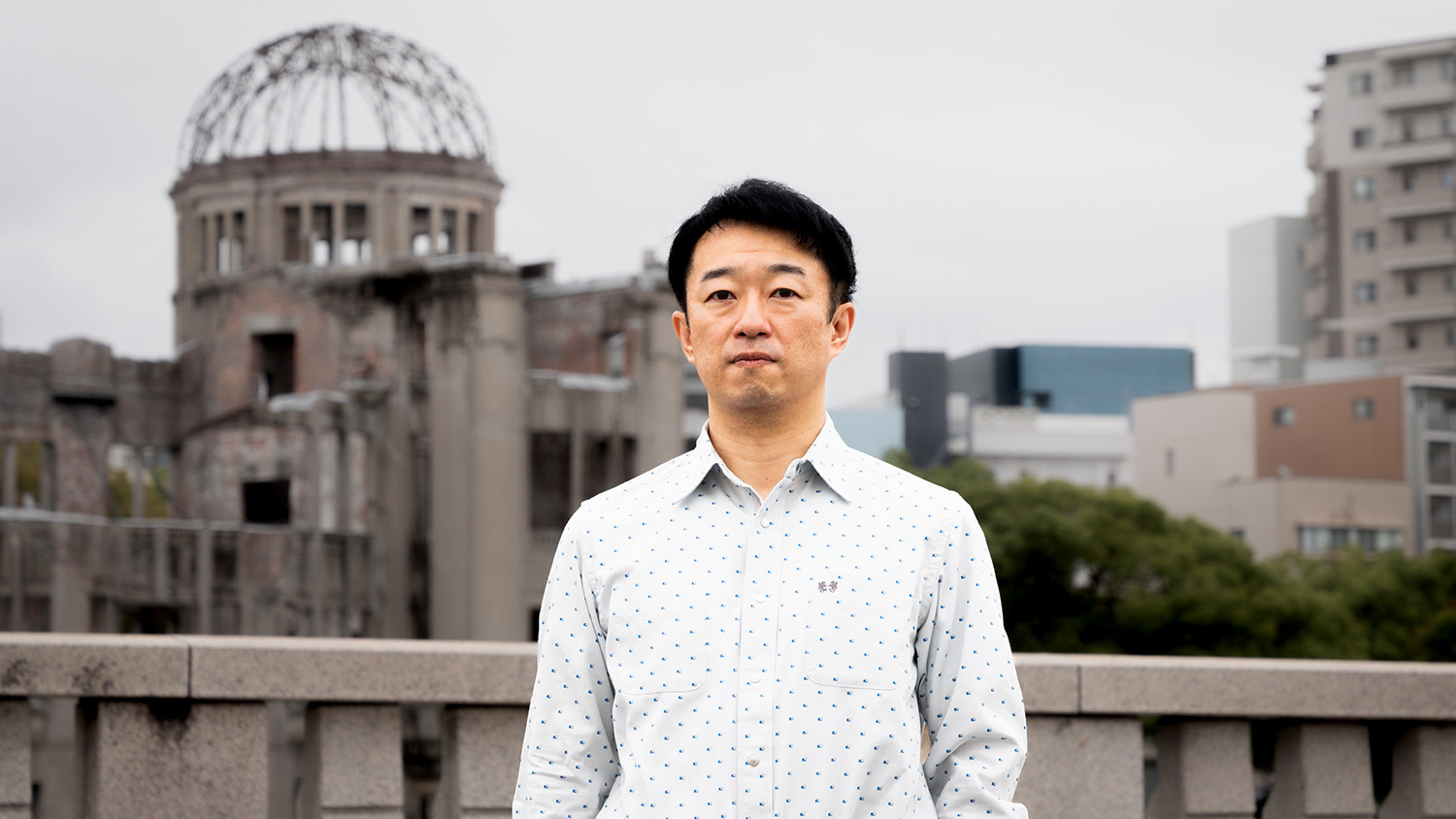

Munechika Misumi ’07 MS studies the effects of the atomic bombs at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation in Hiroshima.

Munechika Misumi ’07 MS is a biostatistician whose task is grim but necessary: To understand the effects of the world’s first atomic weapon — dropped on Aug. 6, 1945 — on those who lived through the blast.

From a research center in Hiroshima, Japan, Misumi studies the survivors — and their descendants — of the atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He is an assistant department chief at the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, a joint venture between the Japanese and U.S. governments to understand the long-term effects of those bombs. Believed to be the world’s longest-running international research organization, the RERF is a continuation of the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission set up in 1946.

The information he studies includes data like blood tests from survivors (dating back to the 1950s and continuing today), incidents of cancer and other illnesses, and interviews conducted after the bombing.

“Always I try to say, there is a person behind every number that I see,” says Misumi, who has worked at the center since 2008. “Every time I look at the data, I tend to imagine the situation the disaster caused. And how hard the environment was that they survived.”

Always I try to say, there is a person behind every number that I see. Every time I look at the data, I tend to imagine the situation the disaster caused. And how hard the environment was that they survived.

The bombings were the result of the Manhattan Project and the work of Robert Oppenheimer, subject of the blockbuster movie Oppenheimer. The film has not been released in Japan, and it’s not clear if it will be, according to Variety. (For his part, Misumi says he had not heard of the movie.) The headlines about the movie come at a time when Japan pauses to remember the devastation inflicted on the two cities.

On Aug. 6, thousands will gather in Hiroshima’s Peace Memorial Park to mark the anniversary of the bombing. With the Japanese prime minister and the secretary-general of the United Nations present, bells ring, sirens wail, and then a moment of silence is observed at 8:15 a.m., the time of the bombing.

Early August is also when the RERF holds an annual open house, and survivors can visit the place where scientists are studying the effects of the bomb. “We have the opportunity to communicate with some of them,” Misumi says. “Some of them are interested in how much radiation they got from the A-bomb. If they ask, we answer their questions.” The conversations are difficult. “Sometimes it makes me’’ — he searches for the right word — “scared, listening to the experience.”

Sometimes it makes me’’ — Misumi searches for the right word — “scared, listening to the experience.

An estimated 120,000 people were killed by the bomb in Hiroshima and another 70,000 in Nagasaki. The RERF has been studying a large cohort of 120,000 survivors, about 70 percent of whom have died. (The average age is 85.) The center has also been tracking data from a smaller cohort who come to the clinic every other year for a medical exam, where blood, urine and sometimes tissue samples are taken. Children of survivors are also studied.

Much of Misumi’s work involves uncertainty and how to account for it in statistical studies. He is particularly interested the lack of certainty around how much radiation each surviving victim received. The RERF and its precursor, the ABCC, established a dose for each survivor based on that person’s location at the time of the blast and anything that shielded them, such as a house or building.

But the memories of the victims about their locations were not always reliable. “Some of them were interviewed 10 years after bombing, and some answered differently when asked multiple times,” Misumi says. “When we try to see association between the radiation dose and cancer, if we use the estimated dose with error, we tend to underestimate risk of cancer incidence,” he says. “We know that through statistical theory.”

Misumi originally hoped to be a physician — a surgeon — but a mentor at the University of Nagasaki urged him to study biostatistics in the United States. Misumi was not sure where to go — but he was a basketball fan. “All I knew was Michael Jordan, that he went to UNC-Chapel Hill,” Misumi says. So he moved to North Carolina, enrolled in Durham Tech, prepared for an exam required for students who speak English as a second language, and applied to graduate schools (and attended a few basketball games at the Dean Dome). He ended up enrolling at NC State, thrilled to be with one of the first statistics departments in the United States. “I knew of the history of the department,” he says. (Misumi now follows Wolfpack basketball from Japan via YouTube.)

Today Misumi is helping launch new studies looking at genomic data from survivors and their offspring. He recently received training in genomics data analysis at Kyoto University’s Center for Genomic Medicine.

His studies have included survivors who were in utero at the time of blast. When looking at non-cancer causes of death for this group, Misumi took into account effects of losing one or both parents, poor sanitary conditions and the loss of their home. That meant reading original interviews of survivors collected by the ABCC, the precursor of the RERF.

“Some of the real situations they reported were really difficult to absorb,” Misumi says. “After the bombings, their houses, their environment was all gone. Nothing was there. . . . It and sometimes made me emotional or made me scared. Sometimes we can find unbelievably bad situations. That made me depressed, reading that kind of material sometime made me unhealthier mentally.”

“I just hope,” he says, “human beings never use nuclear weapons. I don’t think anyone can use that ever again.”