Clearing the Air

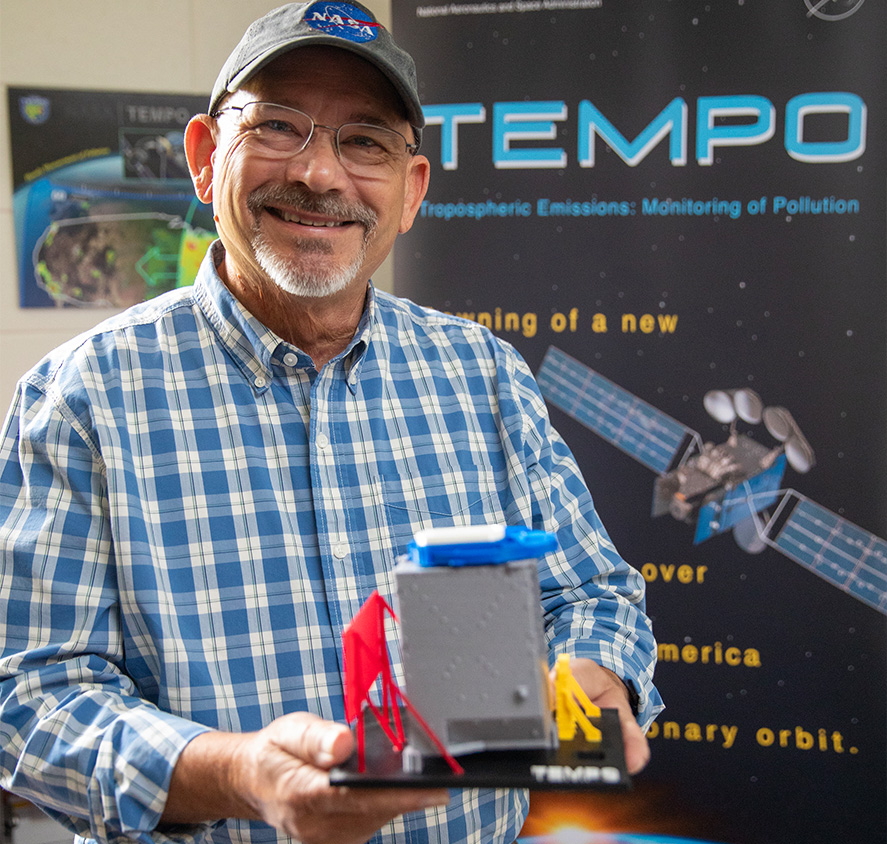

Robert Neece ’80, ’83 MS, ’86 PHD caps NASA career with launch of device to track air pollution.

By David Menconi

Some kids grow up wanting to be movie stars, ballplayers or firefighters. Robert Neece ’80, ’83 MS ’86 PHD, wanted to be an electrical engineer. Perhaps a scientist, too — maybe even at NASA. In his case, all of it came true.

Neece has been a research engineer for 35 years at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va., developing a specialty niche of observing and measuring atmospheric pollutants. He’s closing out his career on a high note, heading up an agency program dubbed TEMPO (Tropospheric Emissions Monitoring Pollution).

What is the TEMPO Satellite?

On a satellite launched in April 2023, TEMPO is a boxy spectrometer flying over North America. For the next two to 10 years, however long it lasts, TEMPO will collect hourly high-resolution measurements of air pollution from Mexico City to northern Canada.

Nearly a decade in the making, TEMPO is part of a global initiative in which similar devices are being launched to take measurements over industrialized regions of Europe and Asia. It’s ambitious enough that Neece, who turned 70 in October, put off his retirement for several years to get it up and running.

“I’m ground systems lead, which means I’m concerned with everything going on in both directions,” Neece says. “That starts with commands from the ground up to the instrument, and then getting data from the satellite to the ground — receiving, storing and archiving science data results.”

We’re still affected by it whether we can see it or not.

How does TEMPO Measure Air Pollution?

There will be plenty of long-term uses of the data for research into climate change, most notably tracking the amount and origin of pollutants. And because TEMPO will measure air pollution in real time on a higher-resolution scale than ever before, it should enable air-quality forecasts of unprecedented precision.

“Pollution tracking and prediction will tell you what to expect, and not just where it is but what it is,” Neece says. “The first TEMPO data that came in captured invisible plumes from the Canadian wildfires in Hampton Roads, Va., where I live. They were invisible. But we’re still affected by it whether we can see it or not.”