Trophy Life

In a career of countless wins and last year’s Final Four run, Wes Moore’s true legacy is family.

Last fall, Katie Burrows got together with some former teammates from her days playing guard in the early 2000s for the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. They dedicated part of their visit to checking out a new renovation and addition to their old home, McKenzie Arena.

The trip stirred memories for the former Mocs. They took some pictures and reminisced. Then they had an idea. “Everybody [was] like, ‘Let’s send some pictures to Frankie,’” says Burrows.

“Frankie” is a former office supply salesman and past prison guard who, after those gigs, decided to coach college basketball. He has no children of his own but is himself a fun-loving big kid. He is a homegrown Texan (“I was born in Texas City,” he jokes, “so you can’t get any more Texas than that, right?”), but he’s spent most of his professional life in Tennessee and Raleigh, carving out one of the most indelible legacies in women’s college basketball. He’s won coach of the year awards as well as Southern Conference and Atlantic Coast Conference tournament titles, and his teams have become a mainstay come NCAA tournament time every March. And “Frankie” is a Final Four coach.

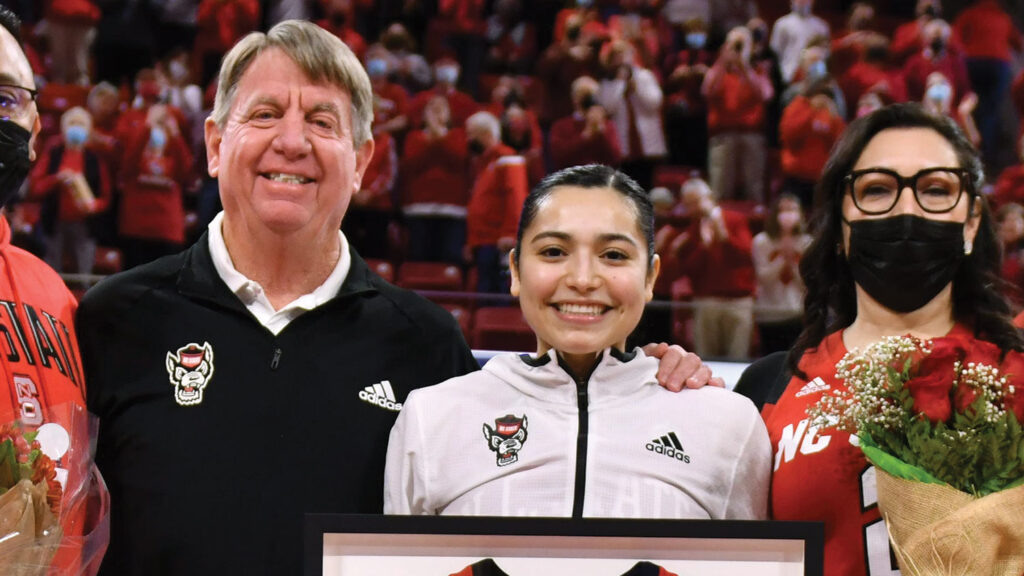

“Frankie” is Wes Moore — “Frankie” from Frank, his given first name. And while his Final Four ride with the Wolfpack in March 2024 would be the apex of a career for most coaches, once you start peeling back the layers to Moore, who is now in his 38th year overall in college coaching and his 12th at NC State, it’s easy to see his legacy is quantified by more than just wins: It’s defined by the family he’s spent three-plus decades assembling.

“We were his children, you know. He’s got hundreds of ‘daughters’ just running around.”

— Katie Burrows

Players from his early days in coaching at Maryville College will tell you this. Those Mocs players who catch up with Moore via texts attest to it. And former and current Wolfpack standouts agree that family is the cornerstone of Moore’s programs. That’s on display in his office where, mixed in with all his trophies and plaques, former star Mimi Collins’ painting of a hoop and Wolfpack basketball sits on the windowsill, showcased like any adoring parent would.

“We were his children, you know,” says Burrows. “He’s got hundreds of ‘daughters’ just running around.”

Finding Family

When River Baldwin ’24 MR transferred from Florida State to NC State in the fall of 2022, she says she felt deflated. She hadn’t been the player she’d expected to be coming out of high school, and her confidence was down. Baldwin, who now plays professionally overseas, says it was Moore’s sarcastic humor, which mirrored her own father’s, that won her over.

Once playing for Moore, she experienced something wholly unique. “His belief in me to be an impact player was something that I had never experienced and no coach had ever given me vocally,” says Baldwin, who posted 21 games in double figures last season on her way to helping lead the Wolfpack’s run.

“His belief in me to be an impact player was something that I had never experienced.”

— River Baldwin ’24 MR

Moore, 67, says hearing such sentiments from former players is an unbelievable privilege. “My current players wouldn’t believe it, but I’ve gotten a few letters through the years,” he says with his trademark self-effacement. “That’s what it’s all about. [It’s] still special when you have that relationship.”

Placing a premium on relationships is something that sprang from Moore’s childhood. He grew up in Carrollton, Texas, a suburb of Dallas. His father left the family when Moore was very young (and he only met him a couple of times as an adult), so Moore grew up in a single-parent home, watching his mother work multiple jobs in the computer and technology fields to support him and his two older sisters. “I can hardly ever remember seeing his mom,” says Gary Jones, a childhood and lifelong friend to Moore. “If we’d go over there, she’d be gone. She’d be at work.”

“I don’t know how my mom did it,” says Moore, who makes a trip to Dallas every year and visits her grave on Mother’s Day (she died in 1978). He remembers the evenings his mother would work the night shift. He’d shoot hoops in his driveway, in the diffuse glow of a streetlight, until well after dark. “This is going to sound crazy,” says Moore, “but I’d sometimes be more afraid of being in the house by myself than being outside by myself.”

But Moore describes his childhood as nothing but a joyous time. He felt his mom’s love, and he forged relationships with a steady group of friends. He’d play football, basketball and baseball with them. He’d head to Texas Rangers games with them. (Still does.) He went to church and traveled with his buddies on choir trips across the country. At church, he also found the Royal Ambassadors (RA), what he describes as a Boy Scouts for the Baptist church. His friends’ fathers would coach his teams, lead RA meetings and take him camping.

With time, his network grew to include other mentors who’d shape his life: A now ex-husband to one of his older sisters, a man everyone calls “Big Jim.” His first college coach, at Dallas Christian College, Gene Phillips. Russell Morgan, who recruited him to play at Johnson Bible College (now University), where Moore would play basketball for a year and then pause his studies for a year to work, earning money to pay for the next year of school. Doug Karnes, who coached him at Johnson, too. Randy Lambert, who hired Moore for his first head-coaching gig at Maryville College in 1987. “I knew after 30 minutes with him [that] he was the person I needed to hire,” says Lambert. Kay Yow, who hired Moore as an assistant coach in 1993 after a chance meeting with him on the recruiting trail and an interview. And Yow’s sister Debbie, who brought Moore back to Raleigh in 2013 as head coach.

A Welcoming Home

Leah Onks-England was named Blount County (Tenn.) Player of the Year twice during her high-school career in the late 1980s. Moore wanted her to join the team he was coaching at Maryville College, where he’d seen early success, taking the Scots to the Division III NCAA tournament. Problem was Maryville, Tenn., was Onks-England’s hometown, and she wanted to go away and had no intention of signing with Maryville. That is until Moore, the pâtissier, showed up with a cake decorated with the number 22 — her number.

“Who do you think baked that cake?” Onks-England, now a middle-school teacher in Tennessee, asks with a laugh. Thirty-plus years later, Moore coyly admits, “My wife made the cake.” And it worked. Onks-England signed on and became one of the most prolific scorers in the school’s history.

Moore met his wife, Linda, who is from Jamesville, N.C., while they studied at Johnson Bible College, and she’s been right beside him as his partner for the last 44 years. He says when he was at his second head-coaching gig, at Francis Marion University, he became keenly aware of how much time other coaches spent away from their families on the road chasing recruits. Moore says it was then that he and Linda decided they would not have children. But Linda is very much a mother figure, supporting the women and opening her home to them for Thanksgiving dinner and to watch Dallas Cowboys games (Wes’ pick).

“He always says, ‘I don’t need kids. I have 15 daughters every year. I’ve got more daughters than anyone,’” says Raina Perez ’22 MR, a transfer guard at NC State from 2020 to 2022. She’s now an assistant coach with Rice University’s women’s basketball. “That family experience is super important to him.”

Senior guard Saniya Rivers says that was one of the main reasons she ended up at NC State. “I’m a family person,” she says. “I came to [NC State] games in high school. So just being able to see that and then [to] obviously come here and be a part of it, I knew what it was going to be.”

Moore’s other recruiting tales end in five-star gets — look no further than Zamareya Jones, a freshman out of Greenville, N.C. — and are full of self-deprecating stories. Like the time he trashed his entire lunch he’d just ordered at Taco Bell to chase down a recruit in Gatlinburg, Tenn., at a Future Farmers of America convention. Or the time he was unaware of a recruit’s phobia. “I had a kid come here to State,” he says. “She flew in at like 11:30 at night. I went to pick her up myself at the airport. I parked and went in. I put the wolf head on. So I’m in the terminal with the wolf head on, and then later I find out she was deathly scared of mascots.”

Attempts at personal touches are important to Moore. Burrows, who, after playing on Moore’s team went on to work as an assistant coach for him at UT Chattanooga before eventually serving as head coach for the Mocs from 2018 to 2022, says he always eschewed the form letter for handwritten notes. And when a recruit was coming to town, Moore would walk the exact path she’d be walking around campus before she arrived to make sure there was no trash and everything looked perfect. “He was very good about making people feel like they were special,” she says, “like they were somebody that matters.”

“He likes to personalize the envelope, personalize the letter, and he’s not going to write the same thing to each kid.”

— Nikki West, Associate Head Coach

Nikki West, Wolfpack associate head coach who has been an assistant for Moore for 18 years, says that’s still alive in his approach. “He likes to personalize the envelope, personalize the letter,” she says, “and he’s not going to write the same thing to each kid.”

Getting the players to Raleigh is one thing. But in an era where it’s easier than ever for players to transfer and leave, keeping them is another. Moore’s ace in the hole is that he is one of the most authentic coaches to ever take the helm of a Wolfpack team, something that calls to mind other Wolfpack legends. “He’s not like anybody I can think of that is in the game,” says close friend and former Texas A&M head women’s basketball coach Gary Blair, who is in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. “The people at NC State should realize that. It’s what made Kay Yow so special. It’s what made [Jim] Valvano so special.”

Sure Moore has the résumé as proof — he’s second in active DI women’s basketball coaches in wins with 851 (and ranks fourth overall in men’s and women’s hoops). He’s won everywhere he’s been: Maryville College, Francis Marion University, UT Chattanooga and NC State. He’s sent players to the WNBA. But it’s his authenticity that leaves a mark. It’s not uncommon for any story you hear about him to end with the teller’s sentiment of, “That’s just Wes.”

Here’s the CliffsNotes of what’s “just Wes”: Everyone — even Moore himself — describes him as frugal. He’s well-known for tasking assistant coaches to go into restaurants on trips to see if they can secure free drinks for the team, a trick he learned from Karnes, Moore’s coach at Johnson. (“Taught him well,” Karnes laughs.) He’s a quick thinker on the court because he’s so prepared by watching game film, but he admittedly struggles to make decisions in life. (“He’s the only guy I’ve ever known that will ask for samples of soup at restaurants,” says Lambert, still a close friend. “He can’t make up his mind between chicken noodle and chili.”) He can be a glass-half-empty type of guy. (“He’s going to let out an expletive in his backswing because he doesn’t think [the ball] is going 225 [yards] straight down the middle of the fairway,” says Blair, also a regular golfing pal.) But that also comes from Moore being a perfectionist. (Perez says he expects his guards to have zero turnovers).

“I kept wondering why everyone didn’t think Wes was the be-all, end-all. Finally, everyone knows what I knew about Wes in those days. … He is not conniving to try to figure out how to be something that he’s not.”

— Grant Allen, childhood friend

Texas friend Grant Allen is tickled that with the Final Four run last March, the entire country got a chance to see Moore’s authenticity. “I kept wondering why everyone didn’t think Wes was the be-all, end-all,” he says of his days palling around Dallas with Moore. “Finally, everyone knows what I knew about Wes in those days. … He is not conniving to try to figure out how to be something that he’s not.”

Deepening Moore’s authenticity are his humility (he’s always deflecting praise to his players) and what Wolfpack associate head coach West calls his passion. Former player Perez calls it his competitiveness and cites it as the reason he relates so well to players. Just go to a practice, where, former Texas A&M coach Blair says, Moore is his best. He plans each one carefully. He directs everything. He challenges his players to absorb what he’s teaching, and when they don’t, he’s hard on them, even his stars. He tolerates excuses about as much as he would a $25 entrée. He doesn’t sugarcoat any of his criticism or frustration. He has pet peeves that will set him off — right-handed layups from the left side, not jumping to the ball, not rebounding and not using the bounce pass enough. But, Burrows, who now is a teacher and high-school basketball coach in Georgia, says he doesn’t get any more mad at his players than he believes them to be at themselves.

Then there are his little sayings: Avoid being a dead squirrel. “He said, ‘Squirrels can’t pick which way they want to go, so they’re dead,’” says sophomore Maddie Cox. Be like McDonald’s fries. “No matter where we go — home, road, wherever,” says Moore, “I want to make sure they know what they’re getting.” “Fresh and salty,” says senior Rivers.

Players laugh when recounting these sayings. And they laugh at the moments when Moore jumps into the fun and lets himself be a kid with them, leaving behind any tensions from practice. That’s a big part of why he’s so popular with his players. He’s on the Jet Ski with them when they travel. He’s learning a new TikTok dance. When the team went to the Bahamas a couple of years back, he went down the waterslides and jumped off cliffs into the water. “I feel like a lot of programs across the country have had coaches who will separate themselves,” says former NC State player Baldwin. “He’s just all about having fun and being involved with the team.”

‘What Can Make Me Feel This Way?’

Moore is certainly a creature of habit. “The old man just has a routine,” says Baldwin. He has his go-tos: Large iced tea, lemons, extra ice. City Barbeque in Raleigh on Tuesday for half-priced ribs. Westerns playing in the background as he watches game film.

“His favorite song is ‘My Girl,’” says former star Collins, who now plays professionally overseas.

Moore joyously belts out the song in practices and at shootarounds. When he sings it, he makes a minor change: he adds an “s.”

“What can make me feel this way?”

“My Girls”

His “15 daughters every year.” His girls.

His family.

Lead photography by Becky Kirkland, NC State.

Tell Us What You Think

Do you have a personal connection to this story? Did it spark a memory? Want to share your thoughts? Send us a letter, and we may include it in an upcoming issue of NC State magazine.