Writing Home

Jai Chakrabarti ’01 reflects on his journey — and those of others — in an acclaimed novel and collection of stories that explore the search for community. Photography by Joshua Steadman.

When Jai Chakrabarti ’01 published his first novel in 2021, he dedicated it to “anyone who’s crossed a border in search of home.” Chakrabarti knows the feeling. When he was growing up, his family split their time between their native India and a series of small towns in North Carolina. He also saw it in the harrowing experiences of his wife’s family.

“I was thinking of my own grandparents, who fled what is now Bangladesh for India,” says Chakrabarti. “They were fleeing religious persecution. I was also thinking of my wife’s grandmother, who has now since passed away, but she was a survivor of Auschwitz and was able to . . . finally settle into Los Angeles and make a beautiful family.

“I was also thinking, more broadly, of the thousands and millions of refugees we have who are struggling to find a home because of various political conflicts around the world.”

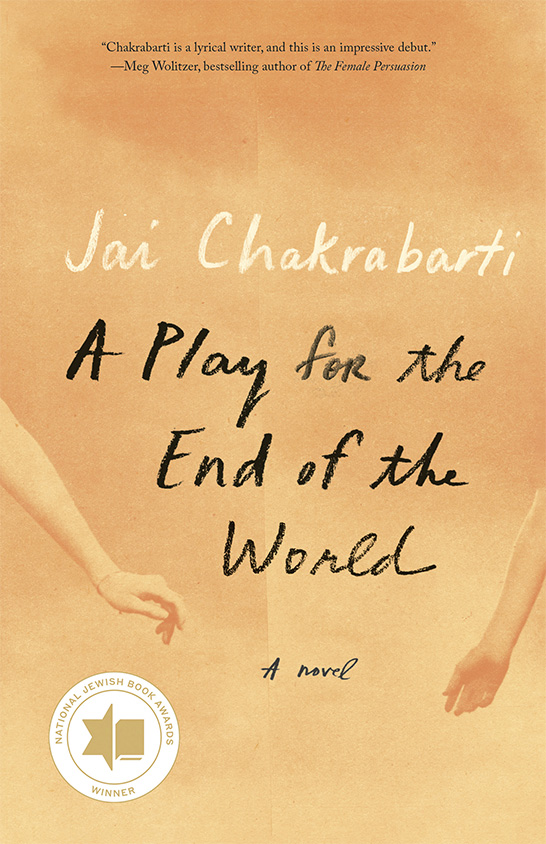

Chakrabarti explored that universal search for home — as well as heightened sensibilities about identity — as he wrote A Play for the End of the World, and a more recent collection of short stories, A Small Sacrifice for an Enormous Happiness, both of which received critical acclaim. The novel was a recipient of a National Jewish Book Award, and The New York Times described the collection of stories as “exquisite” and “impeccable.” The stories explore attempts to build relationships and families across different countries, cultures and religions, while the novel is a work of historical fiction about a survivor of Poland’s Warsaw Ghetto during World War II and his quest to find home in such disparate locations as New York City and a small village in India.

Chakrabarti, 44, lives with his wife and eight-year-old son in New York’s Hudson Valley. In addition to his writing, Chakrabarti has a full-time job as a senior director of engineering at Spotify, the popular streaming music and podcast service. His two roles are reflected in his education — he earned a degree in computer science at NC State before going on to earn a master’s degree in creative writing at Brooklyn College.

The constant juggling is second nature to Chakrabarti, who grew up in Kolkata (the former Calcutta) and learned to read and write in Bengali before learning English. Chakrabarti was comfortable with computers at an early age, designing his first video game when he was 10 or 11 years old. He was also drawn to Charles Dickens and Rabindranath Tagore, an acclaimed Bengali author, poet and playwright, and would write and illustrate his own stories. He found inspiration in a great uncle who loved to tell stories. “A lot of my appreciation of storytelling comes from him,” he says, “just hearing how he constructed a story and how he welcomed everyone in.”

Chakrabarti was nine years old when his family — his parents are university professors, as is his older sister — moved to the United States. It was the first time he wrestled with his own notion of home. The family would spend the school year in America before returning to India each summer, a ritual that Chakrabarti continued through his years at NC State. “My sense is that most immigrants probably feel torn between two cultures and two countries,” he says. “I know I did. I didn’t feel completely at home in America and I didn’t feel completely at home in India either.”

“My sense is that most immigrants probably feel torn between two cultures and two countries.

I know I did. I didn’t feel completely at home in America, and I didn’t feel completely at home in India either.”

—Jai Chakrabarti ’01

While in America, other kids poked fun at his differences, calling him “chocolate bar” rather than Chakrabarti. He remembers going into a convenience store as a teenager, only to have the owner follow him around as he walked down the aisles. While he was a top student in his American schools, he was behind (particularly in math) when he attended summer school in India. “There was an awareness,” he says, “that, okay, I’m someone different from most of the other people that I was around.”

No matter where he was — or what challenges he was encountering — Chakrabarti always knew where he could find refuge. “I had stories,” he says. “I had books, and I had the ability to write. Those were really, really essential tools for me. I don’t think I could have survived without it.”

Despite that draw toward storytelling, Chakrabarti acquiesced to his parents’ desire for him to get a practical degree that would help him get a job. But even as he found technology jobs that he enjoyed, Chakrabarti never stopped writing. When he moved to New York City, he was active in groups that discussed poetry and writing, and it was there that he met his wife, a poet named Elana Bell.

“I see him first and foremost as an artist,” says Bell. “That’s how we connected and the way we bonded and fell in love. At the same time, he’s always had a job in tech. I’ve been impressed by his ability to hold both of those identities. I don’t think it’s easy, but he does it well and fluidly.”

But forming his own family was not without its challenges. Chakrabarti and Bell, who is Jewish, come from cultures where there is often skepticism, at best, of marrying an “outsider.” “Both of us come from close-knit families,” Bell says. “We both carry a lot from our families, in terms of closeness and spending time together and in terms of drawing on the different aspects of our culture.”

Drawing on each other’s culture led directly to Chakrabarti’s novel. During an extended visit to Jerusalem, Chakrabarti and Bell went to Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center. One exhibit, about art in the ghettos where Jewish residents were forced to live, told the story of a Polish educator and author named Janusz Korczak and his decision to stage a performance of a Bengali play in an orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto. Chakrabarti had read the play, which was written by Tagore, one of his favorite authors.

“I can count that day as one of the transformative days of my life,” he says. “Here I was, in Jerusalem, at a Holocaust museum, learning how a Bengali play had been performed in the Warsaw Ghetto. That kind of was what set off the research for the novel.”

The novel follows the main character, Jaryk, from his childhood in Poland and the atrocities of the Holocaust to his life in New York City, his friendship with someone he knew in Poland, his relationship with a woman from Mebane, N.C., and ultimately, his decision to stage the play in a rural village in India. It is a meshing of place, culture and conflict, with characters trying to find somewhere to call home.

When it honored the book, the Jewish Book Council applauded it for a “profoundly moving vision” of the possibility of connection among people who have suffered from oppression and catastrophe. The judges also raised a question that goes to the heart of Chakrabarti’s work: “What does it mean to be a person in this world, to love, to remember, to try to act on behalf of both justice and decency?”

That speaks to what Chakrabarti considers the power of stories — their ability to envision different possibilities, including worlds where people can cross lines of geography, culture and identity and still find a home. He continued to explore that in his second book, which includes stories about a closeted gay man in Kolkata, an adult child using a shared love of painting to reconnect with her dying father and a couple wrestling with adoption.

“I think writing, at its core, is an empathy machine,” he says. “You read a book, and I think you become more empathetic. And if you are reading about people who are from another place, another country, if we’re talking about countries that tend to have a lot of war, you’re going to have more of a sense of why they are coming, why they are leaving that conflict, and I think that’s going to open your heart a little bit more.”

- Categories: