Enough is Enough

Dr. Ashley Hink ’05 takes on gun violence in Charleston, S.C., by treating it as a public health crisis. Photography by Joshua Steadman.

CHARLESTON, S.C. — Dr. Ashley Hink ’05 remembers the moment that everything changed for her as a trauma surgeon and public health researcher. Her experience had exposed her to numerous patients coming into the hospital violently injured, but this scenario was different.

She found herself treating a four-year-old boy who had been shot. And after administering CPR to the boy, she was then treating his father, who was the shooter. Despite her care, the scenario ended up a murder-suicide. And as Hink sat at home later that night, watching the report on the news, she was struck by the missed indicators that the father would shoot his son. The father was a violent felon and had a history of being abusive. He had a history of mental illness. And a friend gave him a gun. Hink asked herself a chain of questions.

“Why don’t we care that more children, teenagers and young adults are being injured and dying from this? Why are we treating them and sending them out without actually addressing their risk factors? And why are we not better addressing all of their needs after they experience this really violent injury?”

“Why don’t we care that more children, teenagers and young adults are being injured and dying from this?”

—Dr. Ashley Hink ’05

Hink, an associate professor of surgery and a burn and critical care surgeon at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), in Charleston, S.C., decided she could answer those questions by addressing gun violence in a state that has the fifth highest firearm homicide rate in the country. And in North Charleston, from 2017 – 2021, aggravated assaults involving guns almost doubled, according to The [Charleston] Post and Courier. So, in 2021, she started Turning the Tide, South Carolina’s first and only hospital-based violence intervention program. Its aim is not to change gun laws or take away anyone’s guns.

Instead, Turning the Tide capitalizes on Hink’s unique position as both a surgeon and public health researcher after years of seeing patients who’ve been shot and coming to understand why they end up in her trauma bay. The program approaches gun violence as a public health crisis and looks to tackle the social factors that lead to the firearm injuries. It offers mentorship and other means of care — from rides to school to assistance with food insecurity — to gun violence victims between the ages of 12 and 30 and their families during their hospital stay and after they’ve been discharged. In three years, Turning the Tide has helped some 360 patients with the goal that they not end up as a repeat victim.

The program is Hink’s way of combatting the perception that gun violence is a fait accompli. “I know that a lot of it is preventable, and I think a lot of people across our country do not realize that, and they think this is inevitable,” says Hink, pointing out that firearms are the leading killer of children and adolescents in America. “This is not normal. There are things that we are doing here that are propagating this problem that can be changed.”

‘MY COMMUNITY’

‘Hink, 40, says when she first started down the road to becoming a doctor, she thought she’d end up a primary care provider or an OB-GYN. That was “where I understood the intersection of public health and medicine to be.” But something clicked with her experiences in college and soon after. While at NC State, Hink volunteered with the Alliance of AIDS Services, which focused on public-health-oriented outreach to AIDS patients, and she started to “really understand and value how human behavior and policies influence health and access to care.” She also volunteered at the Family Violence Center in Chapel Hill, N.C., helping victims of intimate-partner violence. It helped her reach what she calls an “aha moment” of, “Wow, health care is really failing patients that experience violence.”

Hink received degrees from NC State in microbiology and science, technology and society, and a master’s in public health from Emory University. After graduating from East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine, Hink landed in Charleston in 2013 as a general surgery intern and resident at MUSC.

In July 2015, during her residency, Hink was on call when white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine Black congregants at the Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

“We just jump into action to clear out the trauma bay, create an outdoor triage, mobilize other members of the hospital to come down. And we prepared to take care of all these people,” she says, adding that the hardest thing about that night was that she never got a chance to take care of them because of the deadly violence in the church. Only one victim made it to the hospital but did not survive. “To know that it happened in my community, just down the road, to all of these really wonderful people was really awful and hurtful.”

Hink left MUSC in 2018 for a surgical critical care fellowship at Harborview Medical Center at the University of Washington in Seattle. She stayed in Seattle and worked on gun violence injury prevention and intervention with a center affiliated with the University of Washington funded by the Centers for Disease Control. There were more colleagues conducting the same type of research there, and state funds were more readily available in Washington for violence prevention work.

But when the job opportunity at MUSC arose, Hink knew she wanted to return to the South, where there are few hospital-based violence intervention programs and even fewer state legislatures willing to commit money to them. In fact, Hink says, less than 10 percent of all trauma centers in the U.S. have such a program in place. She says that while the media tends to highlight gun violence in cities like Chicago, the highest firearm homicide rates are in Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and South Carolina, areas with some of the country’s least restrictive gun regulations. “In the South, talking about gun violence, you know, she did not pick the easy path,” says Christa Green, a public health researcher who’s the program director for Turning the Tide. “She intentionally took the hard road because she knew that this community deserved it.”

“In the South, talking about gun violence, you know, she did not pick the easy path. She intentionally took the hard road because she knew that this community deserved it.”

—Christa Green

Hink was able to get financial buy-in at MUSC from the provost’s office and the department of surgery, which gave her enough money to start Turning the Tide. (Today, the program is fully funded by 16 external grants.) Using a successful hospital-based violence intervention program in San Francisco as a model, she created Turning the Tide in June 2021. The program now has three client advocates, a program director, an adult trauma injury prevention coordinator and Hink as its medical director.

It’s come full circle for Hink, who’s applying that public-health focus she first encountered years ago in Raleigh and Chapel Hill. Categorizing gun violence as a public health crisis allows Hink and her team to unpack multiple layers as to why it occurs. They can consider how poverty, unemployment, a prevalence of run-down or abandoned buildings, and a lack of green space may impact communities with high rates of violence. “This bears out in the literature,” says Hink, who publishes journal articles on risk factors associated with gun violence. “Those communities, both urban and rural, that have high rates of disparity are significantly more likely to experience higher rates of firearm violence.”

SHOWING UP

Hink says what stands out to her about Turning the Tide’s first three years is how its clients feel seen and heard by the program’s team. Katrina Kiora, 32, who was shot three times by her ex-partner in North Charleston, is one of those. She credits Hink with saving her life and the program with helping her believe in herself, from cheering her on at her job as a manager at McDonald’s to helping retrieve her dog King, an American Bully who ran away the day she was shot. “She basically still has me here,” she says of Hink.

Hink admits sometimes the work is hard and drains her, especially on top of her long hours of surgeries and research. But when she speaks of Kiora or other patients, all of whom she remembers by first name like they’re neighbors, she recalibrates, almost coming back to life. “It comes through,” Hink says. “They’re like, ‘This person actually showed up for me.’”

“It comes through. They’re like, ‘This person actually showed up for me.’ ”

—Dr. Ashley Hink ’05

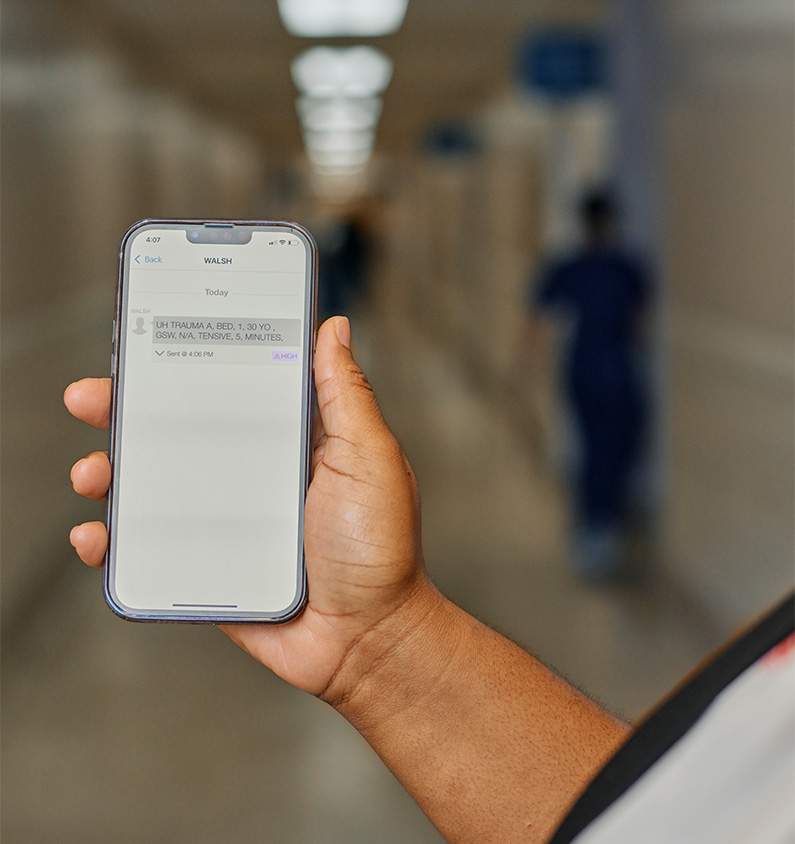

Turning the Tide’s client advocates jump into action and immediately go to work when they get the “GSW” alert — short for “gunshot wound”— coming in on their cell phones. It’s all about those three letters for the client advocates against the backdrop of national victim recidivism trends. The data reveals a blunt reality for victims. Once someone is a victim of a violent injury, they face a higher risk of being victimized by another violent injury as compared to those who’ve never faced being a victim before. “That’s where it sinks in,” says client advocate Keith Smalls of the alerts. “There’s a possibility that it’s somebody that we served before.”

Once the alert comes in, the client advocate heads to the trauma bay. As nurses and doctors clean wounds or put in chest tubes, the advocates wait for an opening to make their introduction. They approach the patient’s bedside to talk, treating the patient with dignity and avoiding language or tone blaming them for ending up a gunshot victim.

The approach is known as trauma-informed care, and it’s one of the program’s tenets. The goal is to consider the patients’ life experiences, make them feel more comfortable and let them know that they have an ally. “A lot come from homes where they don’t have a lot of family support, and poverty,” says Hink. “They might be living in communities with high rates of violence and the presence of crime and gangs. Some of them have never, literally, left their community, and they don’t know what else is out there, and they have been made to feel like this is as good as it gets, and that they can’t be more, and are used to people letting them down, or telling them that they will never amount to anything else.”

Smalls introduces himself and asks about the victim’s family and how he can contact them. “Everything that comes out of our mouth, it’s a sense of encouragement, inspiration, motivation . . . love,” says Smalls. “‘You belong to me now, and I belong to you. We belong to each other now.’”

The client advocate’s work can shift to sitting with friends and families and making trips back and forth to the ER relaying messages. Sometimes, they encounter family members who want to seek revenge for the victim, but Turning the Tide’s client advocates work to quell those situations, as retaliation suppression is one of the program’s main goals. It’s not uncommon to deal with multiple patients at once.

Client advocate Cat Yetman remembers a night where she had five patients, three at MUSC and two at neighboring MUSC Shawn Jenkins Children’s Hospital, which takes patients 15 years old and younger.

At first, the doctors and nurses in the ER were protective of their environment and were curious about the advocates, who are not medical personnel. Eric Schott, a trauma performance improvement coordinator at MUSC, first encountered Turning the Tide’s client advocates as a nurse in the ER two years ago. He says it took about three months or so, but eventually the advocates were a welcome sight. He knew he could focus on medical care while they could be there for the patient in a wholly different way.

“I was always so happy to see them,” Schott says. “I know the patient I’m caring for is going to get something a little bit extra that they may not see anywhere else.”

THE STUFF YOU DON’T THINK ABOUT

Client advocates point out that so many victims of firearm assaults encounter obstacles most couldn’t conceive. It’s the stuff most of us have the luxury of not considering. For instance, Yetman says they had a patient, a mother, who was in the operating room. And her child needed to breastfeed. They were able to ensure the baby received formula and diapers.

It’s just one example of that “little bit extra.” A great deal of that extra occurs when a patient is ready to be discharged. Many times, when a gunshot patient comes in, their clothes must be cut away so doctors and nurses can triage or operate. Turning the Tide’s office is stocked with a cabinet full of shirts, shorts, sweatpants, socks and undergarments so that the patients can leave with new, clean clothes.

Once discharged, they encounter a new list of concerns: food insecurity at home, cell phone service ending if they missed the due date on a bill while in the hospital, and simply feeling safe back in their community. “We do want to see a reduction in what we call recidivism, right? People being reinjured again,” says Yetman. “But what really matters to me is, does my patient go home? Are they safe? Are their families safe?”

Most of the patients who accept after-discharge services and stay on as clients aren’t heading back to the Charleston that was named the top U.S. city to visit in July 2022 by Travel + Leisure magazine readers, welcoming some 7 million visitors per year. In 2022, tourism brought $12.8 billion to the city in hospitality dollars, according to The [Charleston] Post and Courier. Turning the Tide’s clients are heading back into communities like North Charleston, West Ashley and the West Side. Those neighborhoods are home to vulnerable populations, with high poverty and low education rates when compared to the rest of the region.

Gentrification is pushing out residents, most of whom are Black and brown. Some clients are returning to public housing, where renovations and updates are few and there’s pest infestations and dilapidated playground equipment. Corner memorials, with teddy bears and remembrance letters, pay respects to the communities’ most recent murder victims.

Mass shootings prey on our national conscience when they happen. Uvalde. Parkland. Newtown. Naturally, they make us imagine the worst — an active shooter coming into a school and killing our children. But Hink notes that those shootings comprise a tiny fraction of firearm injuries and deaths.

“I think I definitely experienced the shock of mass shootings, but I realized what we all now know,” she says. “Most people that are being shot are being shot all around us every day in our communities,” she says, “and their stories don’t make the headlines. But it’s happening all the time.”

“Most people that are being shot are being shot all around us every day in our communities, and their stories

don’t make the headlines. But it’s happening all the time.”

—Dr. Ashley Hink ’05

Ninety-three percent of patients the program serves are Black, and 84 percent are male. And Green, whose research focuses on violence prevention, says that disparity is underscored even further when it comes to children. In a national study she conducted with colleagues, they found that the rate of firearm homicide deaths for Black children is nine times greater than that of white children. “You can’t really talk about gun violence without talking about racial disparity,” she says, “because a Black person and a white person living in Charleston are living two very different lives most likely on average.”

Community members view gun violence as an existential threat to the health of their communities’ future. Chantelle Mitchell is a community activist, mentor and motivational speaker in Charleston who works with Turning the Tide as a community partner with Youth Advocate Program, a nonprofit focusing on foster care and community-based services. And when asked to articulate how prevalent gun violence is in the community, she doesn’t need statistics. She has firsthand experience. She lost one of the youths she was working with to gun violence back in June. And her daughter lost her best friend two years ago. He was 15. “These kids are out there playing football, double dutching,” she says, “but when you see these kids coming in with gunshot wounds, you have to figure out why.”

And Mitchell says that Turning the Tide has remedied what was a major problem for gunshot victims. “What they realized when they created the program was once [victims] are discharged, no one was following up with them. These are 12-, 13-year-old kids,” she says.

Hink says that three years ago, firearms victims who’d come to MUSC were getting shot, receiving medical care and then being sent back out to those communities with no connection or resources. Now, Turning the Tide helps victims and their families establish lines of credit, stocks their fridges and pantries with food, and encourages them to complete their GEDs and get driver’s licenses. Smalls serves as a father figure to many of his clients, even helping some get staff jobs at MUSC. Talking about those successes makes Smalls smile his gentle grin. There’s also something distinct about his mentorship and satisfaction. He’s personally known the toll of gun violence in Charleston, as his 17-year-old son was shot and killed in North Charleston in 2016.

“I think one of the most serious statements that I’ve ever heard a parent say, that ‘I’d rather go visit my child in jail than visit him at the grave,’” Smalls says. “I understand that point. A gravesite is hard.”

NEXT LEVEL

Hink admits she’s most at home in the trauma bay. It’s there and in environments like the ICU she says she can do what she does best, “creating organization out of chaos,” as she cares for injured and critically ill patients. Hink’s office in MUSC’s Clinical Sciences Building holds a couple of keepsakes that signify her connections to those patients. There’s the painting of a crane by a former patient, and a glass pyramid a former patient’s family gave her. Etched in it is the word, “INSPIRE.”

“There’s a huge difference in the way that Dr. Hink interacts with patients versus maybe other attending physicians or other health care providers,” Yetman says. “She wants to know how patients are doing after she is done caring for them. She thinks about them. She remembers them. She focuses on the humanity of the individual.”

That same level of compassion extends to the fiber of her team’s members. Words colleagues use to describe Hink apply to the program. Sturdy. Strong. Unflinching. Refusing to accept the status quo. “She’s a beast,” another doctor says of her in passing. “She’s next level.”

Hink meets with the Turning the Tide team on Monday afternoons, celebrating their wins with a satisfactory nod. Empathy, too, as she worries about her team. “They come in, and they’re helping patients and families when they are in their darkest moments and they’re terrified,” she says. “There’s a lot of vicarious trauma that those of us experience in doing this work, and they have a really hard job.”

She continues working to ensure that Turning the Tide is sustainable. She would like to hire more client advocates to decrease caseloads. She’s still poring over data from Turning the Tide’s first three years, but says the numbers anecdotally suggest reductions in repeat injuries, an increase in the number of patients returning to MUSC for clinical follow-up appointments and a reduction in unplanned emergency room visits.

Hink also meets with city leaders and politicians, both Democrats and Republicans, who voice support for her work. She looks for more community partners, like schools, criminal justice victim advocates, family counselors, food and housing nonprofits, and law enforcement. She lectures on topics ranging from firearm violence epidemiology to violence intervention strategies. (And she’s a new mom. She and her partner just welcomed a baby girl in December.)

And Hink does it all in her next-levelness to address the essential question that drives her. “At the end of the day, in our country, firearms are the leading cause of death for kids,” she says. “How is it that we are okay with that and we’re not doing more to prevent it?”