Close to the Bone

The N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences’ new Dueling Dinosaurs exhibit builds up scientific exploration

while tearing down the walls between scientist and citizen. Photography by Marc Hall ’20 MA

Paleontologist Lindsay Zanno is trying something different at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences, where she’s head of paleontology and directing Dueling Dinosaurs, a research project and exhibit that opened at the museum in late April.

At the heart of that project are two ancient beasts, a tyrannosaur and a Triceratops from 67 million years ago, seemingly in a tussle. The specimens were found in Montana in 2006. The Friends of the Museum purchased them in 2020 and gifted them to the museum in 2024. They’ve been in storage waiting for this moment. It’s only now that Zanno and her team of graduate students and scientists stretching across disciplines can work to interpret the specimens. Are they indeed fighting? What age is each? And what brought them to the moment where their lives intersected? Those are just some of the questions the Dueling Dinosaurs team will be sussing out over the next several years.

And in answering those questions is where Zanno’s “something different” comes into play. Her team will be doing all of its research directly in front of museum patrons in the state-of-the-art SECU DinoLab, a specially designed lab that marks the first update to the museum in a decade. The museum raised $15 million for the project.

“The whole point was to do all the science in front of the public, so it’s been really difficult to have them here — they’ve been here for seven years now — and not work on them,” Zanno says. “But that was the fundamental goal from the beginning, to not do the research behind the scenes.”

The SECU DinoLab has the technology at the ready for CT scanning and digital imaging that is being done. Laboratory extraction arms stretch down to address the dust and ensure a safe environment. Big screens near the ceiling are displaying the scientists at work. But it’s what the DinoLab doesn’t have that’s most important. There are simply no barriers.

“We decided that we were going to try something really experimental,” says Zanno, who’s also an associate research professor in the Department of Biological Sciences. “We were just going to get rid of the glass altogether, and we were going to invite the public to come inside the lab space, walk into an authentic research lab, have an authentic experience and be able to talk to the scientific team in that space.

“And that, as far as I know, [has] never been done anywhere in the world.”

“. . . We were just going to get rid of the glass altogether, and we were going to invite the public to come inside the lab space, walk into an authentic research lab, have an authentic experience and be able to talk to the scientific team in that space. . .”

–Lindsay Zanno

The Specimens

Zanno admits that she’s not easily impressed. She and her teams have discovered more than a dozen different species of dinosaurs. “I’ve seen a lot of stuff,” she says. “But fossils don’t cease to amaze me.”

Especially Dueling Dinosaurs’ tyrannosaur and Triceratops. Zanno praises them as “incredibly well-preserved” and points out that they both were buried in the Cretaceous period with all of their soft tissues intact, meaning each beast’s bones are in place as if they were alive.

The fossils now sit in pieces like a puzzle. For instance, the tyrannosaur’s skull, its body, the Triceratops’ skull and its hip and chest each sit atop a wooden cart in what is called a jacket, a casing of burlap, foil and plaster. And each rests in a bed of the original dirt from the Hell Creek Formation in the Montana badlands, where the fossils were discovered. All told, it’s a combined 30,000 pounds of fossil and Hell Creek earth.

“It’s essential, when you’re a scientist working on fossils, that you have data that comes directly from when the fossils were discovered,” says Zanno.

The Story

Zanno’s team can look at the fossils and the earth around them to help answer several questions. First off, what is each? “We know that they are a tyrannosaur and a Triceratops, but are they a rex? Are they a Nanotyrannus? Is it a Triceratops prorsus? Or a Triceratops horridus?” asks Eric Lund, manager of the SECU DinoLab. “The other thing that we’re trying to figure out is what brought these animals together. Were they indeed truly dueling as the moniker says? Or was one already dead and one came to scavenge? Or were they both dead and they washed into the same place?”

Part of the research, then, is to look at the specimens almost as a crime scene — let’s call it CSI: Cretaceous —and tell a story. That’s a role Zanno readily accepts when asked if she thinks of herself as a storyteller. “A hundred percent,” she says. “I think this is one of the things that’s incredible about the university-museum partnership, [. . .] we’re training the next generations of students at the university to become storytellers and to learn to translate science into a story so that it can be shared with the public.”

“I think this is one of the things that’s incredible about the university-museum partnership, […] we’re training the next generations of students at the university to become storytellers and to learn to translate science into a story so that it can be shared with the public.”

–Lindsay Zanno

All the members of Zanno’s team, in fact, see storytelling as an integral part of their mission. It’s a team whose members come from a diverse array of disciplines, something Zanno sees as most important about paleontologists: “We have chemists and biochemists. We have physicists. We have engineers. We have geologists. We have evolutionary biologists and ecologists.”

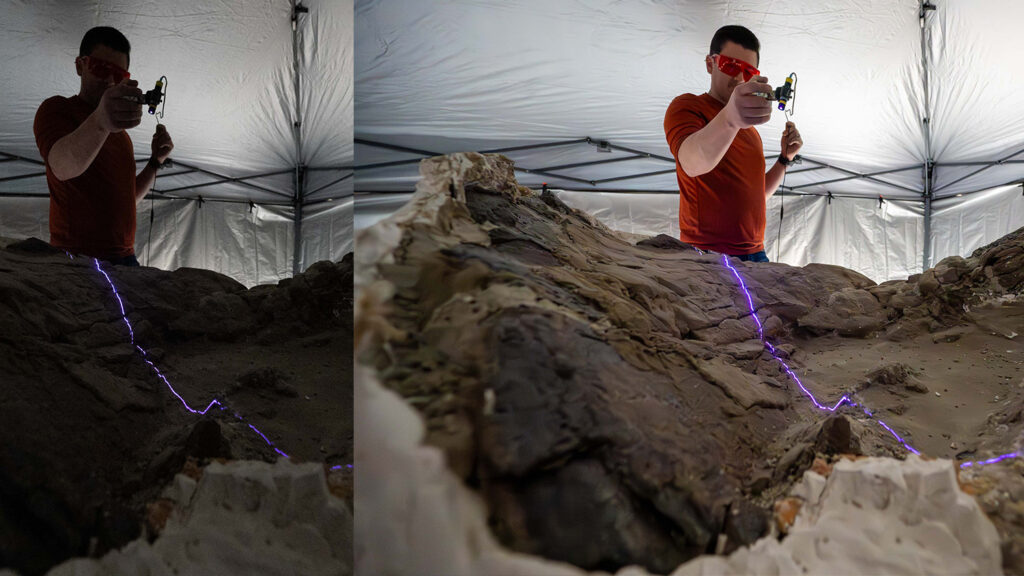

The SECU DinoLab features researchers who employ CT-scans and digital imaging into their work. Some use X-ray fluorescence to learn about the chemistry fingerprint in the fossils and surrounding rocks and plants. Some are experts in paleopathologies, the injuries and diseases present in fossils. And some run high intensity light with wavelengths of lasers across the specimens to find things like feather and skin in the fossil blocks not detected in regular light. For instance, no scientist has ever found a Triceratops specimen with preserved skin impressions from the top of the frill before. Might that change with Dueling Dinosaurs?

Stay tuned.

The Public

Just as important as the specimens, research questions and methods used is the open lab environment and its lack of barriers. That’s what made Jennifer Anné join the project in 2023. “I’ve always loved working in public labs, and so getting to work in a public lab that’s trying something different was exciting,” says Anné, the lab’s assistant manager who specializes in histology, the study of microscopic tissues, and chemistry. “And seeing how much thought was going into this type of lab, just thinking of logistics of fossils and how they were really thinking about making this lab something that was high-quality research as well as something for the public.”

Visitors can also practice what they see. An exhibit space is connected to the SECU DinoLab, where patrons can see what it’s like to CT-scan a fossil. They are able to reconstruct soft tissues of the inner ear and learn how scientists use that information to determine how a dinosaur could hear and what frequencies it might have been able to hear some 67 million years ago. They can take thin sections of bone and count growth lines to determine how old an animal is. And for visitors who can’t make it to the museum, there are livestreams beaming out the work of the DinoLab.

“The greatest aspect of it is it’s allowing the public to have exposure to their natural heritage,” says Haviv Avrahami ’18 MS, a digital technician in the SECU DinoLab. “All of the stuff we’re doing, this paleontology work, it’s our shared cultural heritage. And it’s kind of like the story of the tapestry of life on Earth. It belongs to everyone.”

“All of the stuff we’re doing, this paleontology work, it’s our shared cultural heritage. And it’s kind of like

the story of the tapestry of life on Earth. It belongs to everyone.”

–Haviv Avrahami ’18 MS

And to do so in an environment where there is no divide between scientist and patron (and perhaps future scientist) speaks to what Zanno sees as a pressing need in science today.

“We’ve got an increasing mistrust in science and scientists,” says Zanno. “I think it’s really important that we just break this barrier completely, and we just let people talk to scientists, see who scientists are and what we’re doing, and increase that level of trust and transparency in our communities.”