Chasing a Ghost

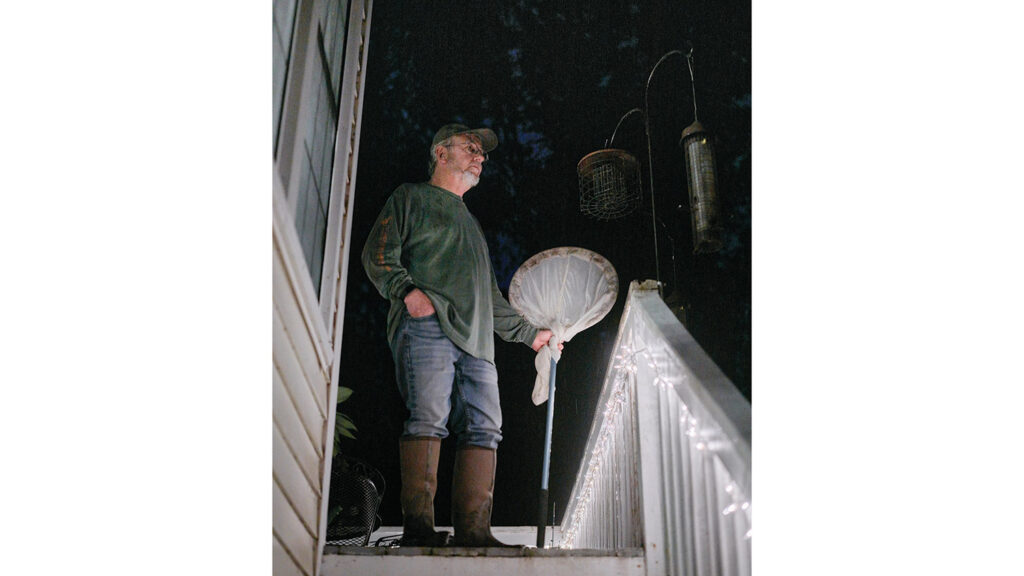

Under the darkness of night, entomologist Clyde Sorenson ’80, ’84 MS, ’88 PHD pursues what could be a new species of firefly. Photography by Joshua Steadman.

The last of the park’s visitors are leaving as Clyde Sorenson ’80, ’84 MS, ’88 PHD and his wife, Lee, pull into the parking lot at the Durant Nature Preserve in north Raleigh. A longtime friend is there to meet up with them, and they spend a few minutes catching up while waiting for it to get dark. They are here to hunt for fireflies.

As anyone who has been a kid knows, there’s something magical about hunting for fireflies on a dark summer night. But Sorenson, an Alumni Association Distinguished Professor of entomology, is closer to retirement than he is to his childhood days, even if he does retain some childlike qualities that endear him to the students he teaches at NC State.

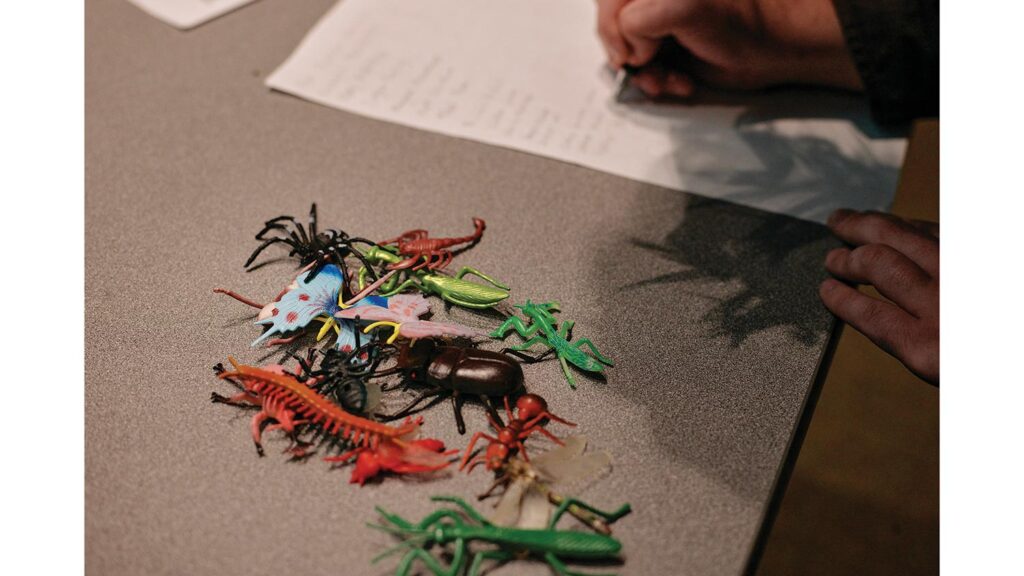

For more than two decades, Sorenson has taught ENT 201, an introductory lecture course on insects. He figures he’s taught more than 8,000 undergraduate students about arthropods and exoskeletons. He’s been known to show up for class in Bostian Hall wearing shorts and a T-shirt covered with scientific drawings of insects. He uses cartoons to make points during lectures and tosses out plastic insects to students who answer questions (or just make him laugh). He calls them “bonus bugs,” and students can turn them in for points toward their grade. He even gets students to eat chocolate-covered crickets and hush puppies made with mealworms.

So it’s not surprising that he’s excited as it finally turns dark on a late spring evening in north Raleigh.

But Sorenson is not just searching for any old firefly. There are thousands of species of fireflies in the world, and Sorenson says about three dozen species have been identified in North Carolina. But none of those are of interest to Sorenson tonight. He’s hunting for what he believes is a species that has yet to be identified. He’s found it in a variety of locations, including the woods behind his house in Johnston County, but he needs more evidence to make the case that he’s discovered a new species.

“It’s a really dramatic demonstration of how much here is still to know,” he says. “There have been folks that you could call naturalists walking around here for 400-plus years. Even though this is one of the most intensely studied patches of ground on the face of the planet — eastern North America I’m talking about, but in particular North Carolina — there are still new things to find, new things to understand.”

“Little Ghosts and Fairies”

Sorensen’s fascination with wildlife began when he was a child, leading him to draw pictures of birds and collect fireflies with his brothers outside their great aunt’s house. His renewed interest in fireflies came about several years ago, when he was hiking the Appalachian Trail in Virginia with his son and some of his Boy Scout buddies. Tired of the racket the boys were making around camp one night, Sorenson wandered off by himself into the woods. What he saw virtually took his breath away. “There were these little blue lights going all through the woods,” he says. “It was really kind of magical. There were maybe a couple of hundred of them.”

When he returned to campus, Sorenson learned through some research that he had stumbled across a species known as the blue ghost firefly, or Phausis reticulata. They are found primarily in the southern Appalachians, and their meandering flight about a foot or two above the ground creates a continuous blur of blue-green lights. They are only visible for a handful of weeks in late spring or early summer — their mating season — and then for only about an hour or so each evening.

As word of the blue ghost spread, they became enough of a draw that tours for people wanting to see them are now offered each year in places like the Pisgah National Forest in western North Carolina. “I like to imagine those early Scottish settlers, coming down from up north — as superstitious as they were — coming into this part of the state and seeing these,” Sorenson says. “They must have been freaked out — all kinds of little ghosts and fairies going through the woods.”

Sorenson’s reaction was a renewed interest in fireflies and learning more about the many species of the insect. “They’re extremely charismatic,” he says. For much of his career at NC State, Sorenson has focused on insects that may not be charismatic, but have an economic impact — agricultural pest management, particularly with tobacco. But his focus over the last 10 years has shifted to conservation biology, and he frequently contributes articles to popular, non-academic publications. “My job is to help discover things and to bring those things to broader attention,” Sorenson says.

“My job is to help discover things and to bring those things to broader attention.”

— Clyde Sorenson ’80, ’84 MS, ’88 PHD

So when Sorenson heard about a couple in Chatham County, N.C., who had reported seeing blue ghost fireflies on their property, he was intrigued and suspicious at the same time. It seemed unlikely that blue ghosts would be found so far from the mountains.

When he and his wife went to Chatham County in 2020, they spotted a dozen or so fireflies hovering a foot or two off the ground, just like the blue ghosts. But something seemed off to him. “It wasn’t as bright as the ghost I was familiar with in the mountains,” he says.

Clyde’s Find

The unnamed firefly species that Sorenson has found is different in key ways from the blue ghost firefly found in the North Carolina mountains. The unnamed species is not as bright as the ghost species found in the mountains. That’s presumably because the female blue ghosts have five to nine light spots, while the unnamed species has two light spots. The males of the unnamed species have smaller light organs than their blue ghost counterparts. There are also subtle differences in the shape and coloration of the fireflies’ shield and abdomen.

Finally, the habitats for the two species appear to be different. The blue ghosts are found primarily in the mountains, while the unnamed species has been spotted in Chatham, Johnston, Montgomery and Wake counties.

The following year, Sorenson used Facebook and other means to ask friends if they would take part in an informal citizen-science project by looking in their backyards for fireflies close to the ground and flashing a blue-green light. John Conners, a friend who had worked for years as the city naturalist for the city of Raleigh, responded with an email saying he had seen fireflies like that before — at a former Boy Scout camp that is now Durant Nature Preserve.

And so Sorenson, his wife, Conners and a few others went out looking at Durant one night, and found dozens of them. He heard from other friends in the area who had found them, prompting Sorenson and his wife to visit several spots around the Triangle to find and collect this new type of firefly. “It was like the magic of fireflies,” he says. “You can get people engaged with these magical little critters.”

“Easier to Care About”

Before long, Sorenson had found what he believes to be a new, still unidentified species in Chatham, Wake and Johnston counties. He wondered if they could even be in the woods behind his house. The answer, to his delight and chagrin, was yes. “After 25 years of living in this house, I discovered something I had no idea was even there,” he says. “I was really, really embarrassed. But, also, it was great. It was awesome.”

Having collected several samples at this point, Sorenson was able to start documenting the differences between the blue ghost and the species that he was finding. The light organs on males of the unidentified species were smaller than those found on the blue ghost, which would explain why the lights looked dimmer to Sorenson. The female blue ghosts typically have between five and nine light spots, while the females of Sorenson’s firefly always had two. There are also identifiable structural differences between the males.

“At the very least, it’s a subspecies of the blue ghost, but in all likelihood it’s actually a different species.”

— Clyde Sorenson ’80, ’84 MS, ’88 PHD

“At the very least, it’s a subspecies of the blue ghost, but in all likelihood it’s actually a different species,” he says. “You’ve got all these morphological differences. You’ve got habitat differences. So there are some pretty dramatic differences.”

Eventually, Sorenson hopes to have enough evidence to make the case — probably in a scientific journal — that he has identified a new species of firefly. If that happens, Sorenson may get the opportunity to give the new species a scientific name and a common name — early contenders are Piedmont ghost and foxfire ghost.

“There’s great power in a name. If you know what something is, it’s a whole lot easier to care about it.”

— Clyde Sorenson ’80, ’84 MS, ’88 PHD

“Science doesn’t give a rat’s patootie about common names,” he says. “It wants the new scientific name. But from a perspective of promoting conservation and awareness, you have to have a common name. There’s great power in a name. If you know what something is, it’s a whole lot easier to care about it.”

“Lots to Learn”

And so the search for more data continues, with Sorenson set to explore the trails of Durant Nature Preserve on this late spring evening. Once darkness settles in, Sorenson and his group head down the trail in search of tiny lights. For several minutes, the only noise comes from the crunch of gravel under feet as the group slowly makes their way down the trail.

Familiar Fireflies

The most common fireflies in your own backyard are more likely to be Photinus pyralis (9–19 mm), a dusk-flying firefly adapted to grassy areas and open woods and one that seems to be adaptable in suburban habitats. It is much larger with distinct pink and black markings on the shield behind its head).

The similar looking Photinus carolinus (11–15 mm), can be found in the mountains of North Carolina during the months of May and June.

The tiny Phausis reticulata (6–9 mm), only appears for a few weeks in April and May, and then again in June and July, and is also found in the mountains of North Carolina.

“Wait, did I imagine that, or did I just see something?” Sorenson asks a few minutes into the hike.

“If you’re not sure, then you probably didn’t,” says Lee, who Sorenson credits with being better at spotting fireflies.

Several minutes into the hike, the group is striking out. “Come on, bugs,” Sorenson says. “It’s like working with children and dogs. They don’t ever cooperate. But these are good conditions. If they’re gonna show up, we ought to see them.” As the trail takes Sorenson and his group deeper into the woods, his frustration grows. “If we don’t see them in the next 15-20 minutes, we’re probably not going to see them tonight,” he says. “This is aggravating.”

At one point, someone spots a couple of tiny lights on the forest floor. Sorenson is quickly on his hands and knees to get a closer look. What they’ve found are not fireflies, but rather a couple of glow worms mating, something Sorenson had never seen before.“ Dude, that was cool right there,” he says. “That was really cool.”

Cool, yes, but not as cool as finding what he’s looking for. Which Sorenson eventually does — when his friend spots a male firefly caught in a spider web, a common way to find samples. “This is our guy,” Sorenson says as he extracts the firefly from the web. Sorenson places the insect in a plastic container so he can examine it later. He’s confident it’s the species he was looking for. But he’s also baffled by the fact that they found only one after finding so many on previous visits to the park.

“The only thing we know about them is that they do exist. We don’t know anything about their biology, except for roughly when adults are active,” he says. “There’s lots to learn.