Homecoming

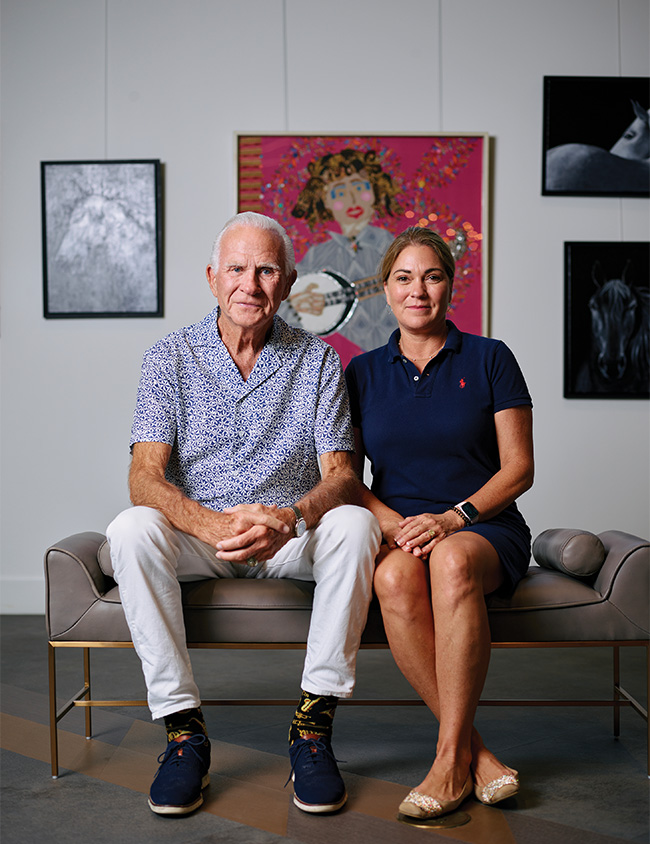

Ed Fitts ’61 could spend his retirement relaxing. Instead, he’s breathing new life into the small North Carolina town where he grew up. Photography by Joshua Steadman

Littleton, N.C. – The massive lumber trucks still rumble through downtown Littleton, hauling timber taken from the stands of pines and hardwoods that hug the country roads, headed to a paper mill east of town. They drive straight through, stopping only at the single stoplight in town.

Not long ago, the trucks drove through a nearly empty town. But today there are cars parked along Main Street, in front of the library, an upholstery shop, a nail salon, a clothing store, a thrift store. And then there are the new businesses — a coffee shop, a wine store, an art gallery and an upscale restaurant — all of them filling in what were previously vacant storefronts.

Just down the road is the Littleton High School building. The school closed its doors in 1973, but its auditorium has been renovated into a state-of-the-art performance venue. In the refurbished gym, new hardwood floors shine while students from Littleton Academy study robotics and financial literacy in a K-6 private school that opened next door to the arts center. Nearby, bulldozers work the old football field in preparation for a 150-seat outdoor amphitheater that will bring free concerts to the community.

This new activity in Littleton — a small town near the Virginia border and the shores of Lake Gaston — is due to the investment of Ed Fitts ’61 and his wife, Deb. Fitts grew up in a small white house near downtown, raised by a single mother. After getting a degree in industrial engineering at NC State, he went to work in the packaging industry and built a company that became one of the nation’s largest suppliers of fast-food containers. After he sold the company, Ed and Deb Fitts opened a winery in Napa Valley, but sold it in 2019, leaving them free to turn more of their attention to Ed’s hometown.

Littleton, like many small towns across North Carolina and the nation, has been steadily losing population, going from 1,000 in 1960 to a little over 600 today. Until recently, most of its downtown businesses were long shuttered. The last train came through in 1982. While Lake Gaston draws owners of vacation homes and day trippers, most travelers had been skipping over Littleton. But since the Fittses began their effort to revitalize Littleton about five years ago, Littleton is becoming a destination. So far, they have opened an upscale restaurant, a coffee shop and a wine store, renovated the old high school building and turned part of it into the Lakeland Cultural Arts Center, and opened a private K-6 school with scholarships available for any student in need.

If you’ve heard of Fitts, it’s likely because his name is on the new Fitts-Woolard Hall on Centennial Campus and the Edward P. Fitts Jr. Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering in recognition of his transformational philanthropy. But you won’t see his name on anything in Littleton — not the school, not the arts center, not the restaurant. The only outward signs of his influence are the paper signs posted in the windows of the library and town hall directing patrons to connect to WiFi at the Ed Fitts Charitable Foundation, which brought connectivity to a town that had been bypassed by efforts to bring broadband to rural areas.

“In every small town, there’s somebody who made it,” says Stacey Woodhouse, a former Warren County, N.C., economic development director who now consults for the Fittses. “But the difference is, they don’t come back to help.”

“In every small town, there’s somebody who made it. But the difference is, they don’t come back to help.”

— Stacey Woodhouse, Consultant

A Teardown

In some ways, it started at a class reunion. The Littleton High School Class of 1957 — often joined by folks from the classes of ’56 or ’58 — get together nearly every year. “We rented a place at the lake,” Ed says. “People would come for the day and picnic and bring a covered dish the way people do.”

Deb chimes in: “We’d watch a game, have dinner, talk — it was a weekend outing. The guys all played sports together. They would talk about the games.”

“How we beat them up and who scored what,” Ed says, filling in the sentence the way married couples sometimes do.

It was at one of these gatherings in 2017, as Ed Fitts remembers it, that “Terry Newsom showed up with a piece of paper in his hand.” Newsom was on the board of directors of the Lakeland Cultural Arts Center, a small community theater organization that had been operating out of the old high school building. He’d signed a note for a loan of nearly $200,000 to pay for roof repairs and it was coming due. Could Fitts help?

Fitts had already pitched in here and there around town. In 2014, he’d helped the library get a new location, telling them if they would raise $25,000, he would match it. They did and he did. He’d helped pay for the planting of the crepe myrtles that still bloom along the downtown streets.

Deb and Ed agreed to pay for the new roof. Then, like a home renovation project — the kind where you start out to replace the cabinets and then realize you need to replace the countertops too — one thing led to another. The school building was in worse shape than they realized. The roof was leaking so badly that kiddie pools on the second floor were used to catch rainwater.

The volunteer group that had been running the community theater had not had the funds to maintain it. The school gym — where Fitts was the leading scorer on the basketball team his senior year — had been abandoned for years and was in danger of collapse.

“We walked in — it was a teardown,” Deb Fitts says.

“A disaster,” Ed says.

In the gym, the walls were falling in, the hardwood floors had two feet of water underneath. There were broken windows, holes in the floor from rot.

“I can’t bear to see my high school like this,” Fitts remembers thinking.

“I can’t bear to see my high school like this.”

— Ed Fitts ’61

Stretching a Dollar

Ed Fitts was born in Macon, N.C., a crossroads near the train tracks down the road from Littleton. His mother and father separated when he was five. He and his mother and older brother moved in with his grandparents in a 3-bedroom home in Littleton.

His mother got child support of $25 a month for each of her sons, and raised the family on that income along with occasional stints working as a practical nurse or painting portraits for folks in town. “She was so frugal she could feed a family of five on $10 a week,” Fitts says. “She could stretch a dollar further than anyone you knew.” He remembers home-canned butterbeans and tomatoes. Potatoes and onions were stored under the house, which was raised up off the ground with no cellar, and on winter nights the wind would come through the floorboards in his bedroom.

“We were poor,” Fitts says. “But the good news is, we didn’t know it.”

Fitts started earning his own money at age 12, delivering newspapers for $5 a week on a

3-mile bike route. Collection day was the hardest. (“The front door would open — and then you’d hear the back door slam,” he says, adding that someone on that route still owes him 85 cents.)

“We were poor, but the good news is, we didn’t know it.”

— Ed Fitts ’61

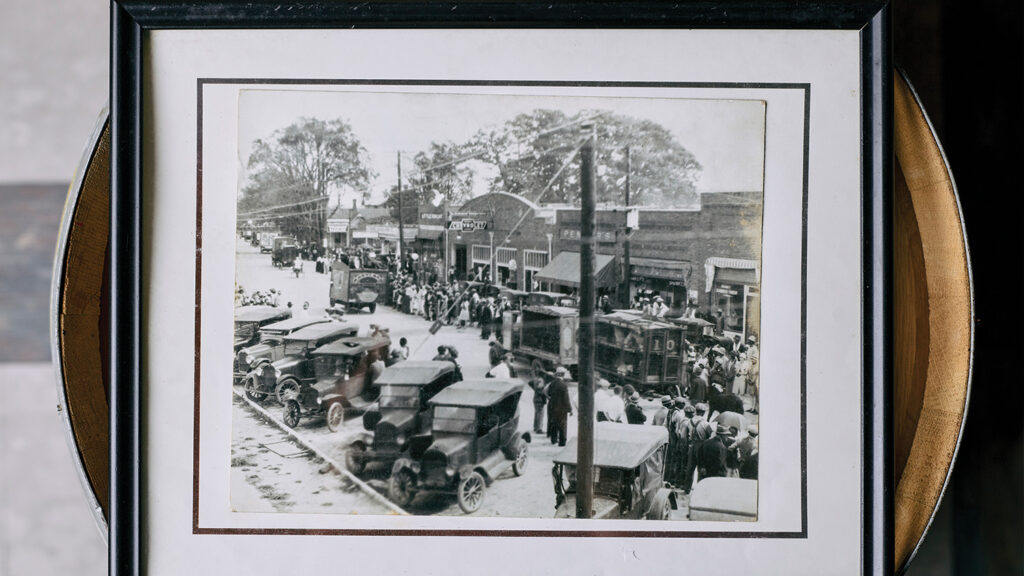

Back in those days, the train carried bales of cotton through Littleton. That was long before the Roanoke River was dammed to create Lake Gaston, which straddles North Carolina and Virginia and is now the site of thousands of vacation homes. Fitts remembers the river crossing at Eaton’s Ferry — now the name of a marina on the lake — where a raft went along guide ropes pulled by mules on either shore.

In high school, Fitts took Latin and agriculture. He played football, basketball and in his senior year, baseball. (“They only had eight guys,” he says.) He still has the poster with the 1956 football game schedule, with a score written in pencil beside each date. In 1957 he graduated along with 22 other classmates in the high school auditorium, enrolled at NC State and headed to Raleigh. An uncle had left him some money to help pay for college, and he paid for a semester by working at a paper mill in Roanoke Rapids.

“Then I had to borrow money from my mom for my senior year,” Fitts says. “I paid it back in two years.”

Once-in–a-Lifetime Opportunity

Today Fitts is tall and lean with piercing blue eyes and a shock of well-groomed white hair. At 83, he grabs a cane when he needs it. He’ll wink, tell you a dad joke, and stop a conversation to say: “Funny story about that.” And it usually is a funny story — or at least an interesting one. Like the time he and Deb hosted the entire Cleveland Cavaliers team, including LeBron James, at their winery for a wine-tasting.

In the days before the Lakeland Cultural Arts Center’s grand opening in September, he’s in the lobby and passes a young man sitting behind a desk with a sign: “WILL CALL.” “So,” Fitts says to the man with a wink, “Your name is Will?” They laugh, and Ed puts out a hand and introduces himself as he does to most everyone: “I’m Ed Fitts.”

People describe Fitts as down to earth. “I have been around other people who are extremely wealthy, and they make sure you know it,” says Angel Jones, the assistant head of school at Littleton Academy. She remembers sitting beside Fitts at a meeting and not realizing who he was. “You wouldn’t know it’s Ed and Deb Fitts unless you know it’s Ed and Deb Fitts,” Jones says.

The couple maintains homes in Florida, Pennsylvania and Cabo San Lucas in the Baja California section of Mexico. So it makes some sense that they would add a house in Ed’s hometown to the list. Two years ago, they renovated a 1940s brick house only a few blocks from downtown, not far from Fitts’ childhood home. “We knew if we were going to do this, we couldn’t have a house on the lake,’’ Deb says. “We needed to be part of the community. We needed to be in town.”

Once they decided to fix up the school building — creating both an arts center and eventually a school — they started to wonder what else they could do. The couple went to town council meetings, getting a play-by-play from locals on small-town politics. They asked for a top-10 list of needs. High on the list: Do something about the uninhabitable abandoned houses along Ferguson Street on the way into town. The Fittses arranged to tear down the dilapidated housing, which had been vacant for decades. Today the vacant lots are kept neat and mowed.

And then there were the vacant storefronts — a row of them on the south side of the Main Street. “When we would drive through town, it was so depressed, it felt like there was nothing anybody could do,” Deb says. “The buildings were unrentable, unusable.” The Fittses bought the buildings and began a massive renovation.

Below right, Chef Ashley Fleming makes biscuits for a dinner service.

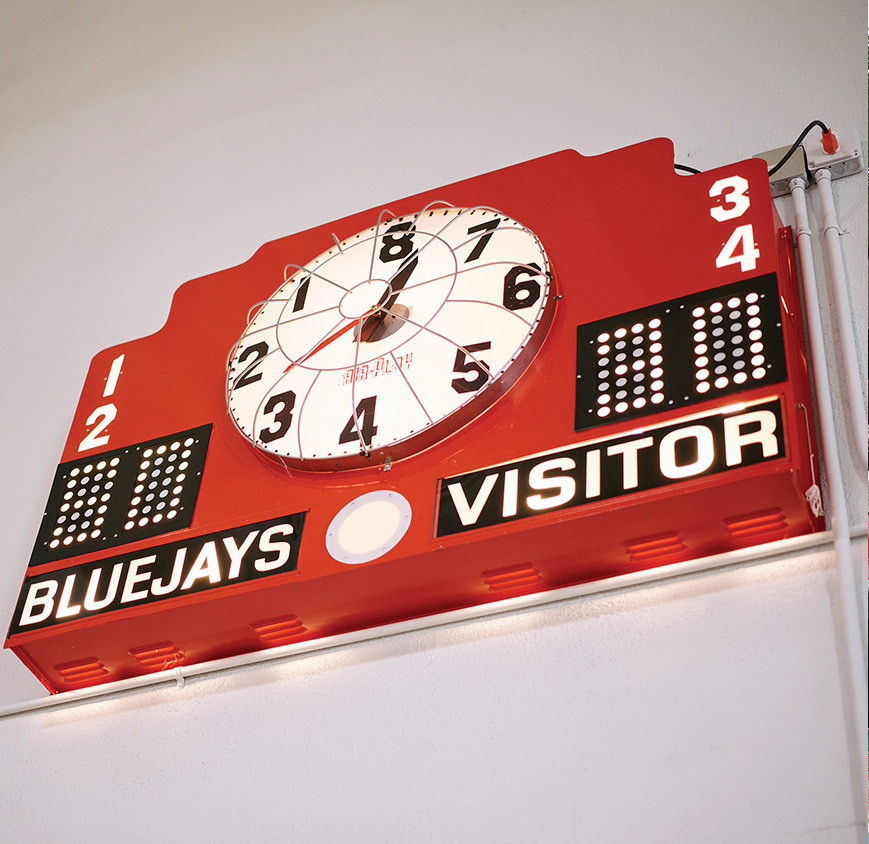

Locals wanted a place to gather, so the Fittses opened a coffee shop. It’s called Daphne’s, after Fitts’ mother. Her portrait adorns the brick walls of the shop, along with some of her oil paintings. Next door is a wine shop. They brought in an executive chef to run the Blue Jay Bistro — its name a nod to the mascot of Littleton High — which bills itself as “approachable contemporary fine dining.” A recent menu included black-tea brined pork chop with blueberry barbecue sauce. All the profits from the businesses help pay for what the Fittses see as their most important investment — Littleton Academy. This, they say, is about the future. The purpose is twofold — to provide a great education for kids in the area, and to end what Deb Fitts calls the generational poverty in Littleton, where nearly 25 percent of the population lives in poverty. The school is private, but only a few students are paying full tuition. The rest are on financial aid.

The school and the Lakeland Cultural Arts Center share more than the same campus. In September, the arts center re-opened with a performance by the Florida-based Sons of Mystro, two electric violinists who play everything from rap to classical. That afternoon, the duo played a special concert for Littleton Academy students, along with public school children. “We brought in 160 students from Warren County, one of the poorest [counties] in the state,” says Peter Holloway, executive director at Lakeland.

Holloway came from Louisville, Ky., where he ran a successful children’s theater. When he heard what the Fittses were doing to bring the arts to a small town, “I just thought, ‘That’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity . . .’”

The spacious sleek lobby of the arts center doubles as an art gallery and an event space. Holloway says the tech crew that installed lighting and sound systems told him it was the best-equipped theater in the state (and that includes DPAC in Durham). “This building is astonishing,” he says. “You would never expect to find it in a town of 600. There are towns of 250,000 that would kill to have an arts center like this.” But the original touches of the 1923 school building remain: The proscenium arch that frames the stage is the original plaster, set with painted silver stars.

Holloway wants to bring a variety of entertainment at different price points — from free movies to community theater and traveling productions — that will attract patrons from surrounding counties as well as folks in town. “There are 20,000 homes on the lake,” he says. “Those people are from the Triangle or Richmond — summer homes or secondary homes. They are well-educated, used to traveling and seeing shows. But in town, you’ve got a big segment where arts are not a part of their life.”

Throwing Snowballs

Ed and Deb Fitts play off one another and egg each other on.

“Our problem has always been, sometimes we don’t know what we can’t do — so we’ll try most anything,” Ed says.

“We’re a horrible team,” Deb says. “He’ll come up with an idea. And I’ll say, ‘OK, we can do that.’”

“Deb says, ‘You make the snowballs and I’ll throw ’em,’” Ed says.

The Fittses are not done throwing snowballs. A brewery called Timber Waters will open later this year. “Timber for the lumber industry, and water for Lake Gaston, which helped keep the town alive,” he says. There are plans for an upscale market and a boutique hotel. And down the road, the Fittses hope to build affordable housing on 43 acres.

They proceed carefully with each project, getting the blessing of the town council even with issues that don’t typically need approval. They were ready for skepticism. “We were definitely concerned with people worrying about what we were doing — ‘Are they trying to take over the town?’” Deb says.

Stephen Barcelo, a town council member from 2017 until last year, was impressed that the Fittses kept in close contact with local officials. “They came and asked us, ‘What do you want?’’’ Barcelo says. “Most people will come in with a grandiose idea and then scale it back,” he says. “But this is the opposite. They came in big and it’s getting bigger.”

So far, the Fittses figure they’ve created about 50 jobs in town — not counting the employment generated by construction and renovation. Ed doesn’t specify how much he’s spent, but puts the number somewhere near what he’s donated to NC State, about $35 million.

Kim Gray, manager of the Littleton Library, and her sister, Tracy, say they worry about the town becoming too gentrified. “We want it to succeed,” Tracy Gray says. “But we don’t want to see the people who are from here get pushed out.”

But overall, Kim Gray says, the changes are positive. “Our daddy can remember when this place was hopping. Trains coming through. There was even a taxi service,” she says. “Then that stopped and there were times when not a car was parked on Main Street.” Now traffic is back, and Gray loves it when the children from Littleton Academy walk to the library. “It does my heart good to see it,” she says.

And, she says, it’s ultimately the people who make the town. “It’s always been a special place. It’s about neighbors helping neighbors. All this,” she says, waving her hand toward the businesses across Main Street, “is just icing on the cake.”

If you’re talking about Littleton neighbors helping neighbors, Fitts will tell you he has a story about that.

He and his brother used to throw a baseball back and forth in the yard of the white house on College Street. There was a neighbor who lived nearby, an older man whose children were grown. “One day he came outside,” Fitts says, “and said, ‘Hey, why aren’t you boys wearing gloves?’ “Our answer was, ‘Don’t have any.’ The next day he gave us each brand-new baseball gloves. They were Rawling’s.

“I never forgot that.”

- Categories:

I am a prior Littleton resident and have never forgotten the beautiful little town I grew up in. I was really heartbroken to hear my school was falling down. It meant a lot to me. I am so proud and thankful the Fitts’ came back and are now rehabilitating the town especially our school. I wish I was able to move back and one day be laid to rest there. While growing up there the people in Littleton looked after each other like they were family. I cannot imagine there is another place in The United States that is as attractive in as many ways as Littleton is. Thank you from the bottom of my heart to the Fittses for rescuing that beautiful little town. May God Bless You!

I am a prior Littleton resident and have never forgotten the beautiful little town I grew up in. I was really heartbroken to hear my school was falling down. It meant a lot to me. I am so proud and thankful the Fitts’ came back and are now rehabilitating the town especially our school. I wish I was able to move back and one day be laid to rest there. While growing up there the people in Littleton looked after each other like they were family. I cannot imagine there is another place in The United States that is as attractive in as many ways as Littleton is. Thank you from the bottom of my heart to the Fittses for rescuing that beautiful little town. May God Bless You!