Walking Her Path

A new book by Natalie Chanin ’87 explores lessons learned in her career as a “slow fashion” trailblazer.

As Natalie Chanin ’87 looks back on the career she’s built in the world of fashion design, it’s easy to get confused. Her decision to leave the industry’s epicenter of New York City to return to her home state of Alabama was, by any measure, a non-traditional path to success in the fashion business. But then the reason she was returning home more than two decades ago was to create locally-sourced, sustainable apparel, a traditional, time-tested approach that would come to be known as “slow fashion.”

No matter whether you consider it traditional or not, Chanin’s choices have worked. She’s built a successful business, Alabama Chanin, she’s seen others take up her mantle of a sustainable approach to fashion (“I see the needle pushing forward, but I wish it was faster.”), and she’s created a culture that values the work that goes into both the designing and making of the apparel she creates.

And she’s done it all from Florence, a small town in the northwest corner of Alabama.

“I thought I was coming home for a one-month project,” Chanin says, “and I’m still here 22 years later. It was definitely not what I expected. But this is the path that I walked. I feel very grateful and lucky to have walked this path.”

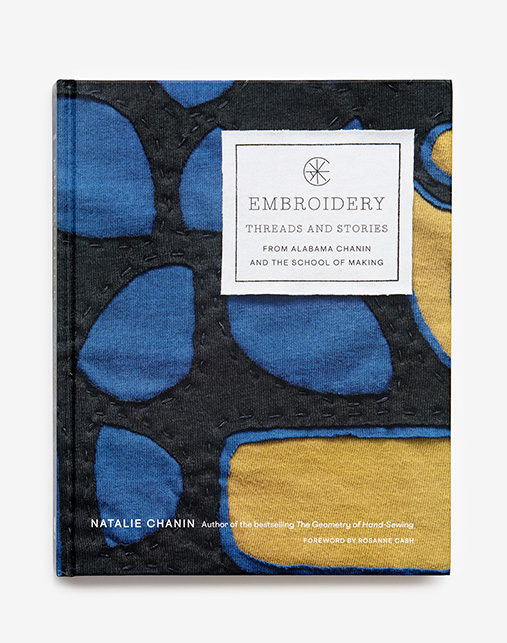

Chanin has reflected on that walk in a new book, Embroidery: Threads and Stories from Alabama Chanin and The School of Making.

“The book is a really personal story about my coming home, but it’s also a story about community and, I guess you would call it, creative place making,” she says. “I would hope that readers find the inspiration to make what they want where they want to make it, hopefully to the benefit of the community that they’re making it for.”

The book comes at a time of transition for Chanin, 60, who says it will be time soon to step back from running her business so she can spend more time teaching, writing and working on other projects.

One of those projects is a nonprofit organization she founded called Project Threadways that is exploring the history of textiles. When Chanin returned to Alabama in 2000, she could see how the North American Free Trade Agreement had devastated the textile industry throughout the South, leading to the shutdown of countless plants. She was drawn to the stories of the people who worked in those plants, as well as the farmers who grew the cotton that was used to make t-shirts, socks and other apparel.

“As Americans, we began to look down on factory work,” she says. “We saw it as a lesser existence, which was really not the truth. Most of the workers we interviewed saw themselves as artisans. My little community was known as the t-shirt capital of the world. We were making the highest quality t-shirts and other apparel anywhere in the world. It was very hallowed work. We’ve tried to shine a light on it and change the way people think about this work.”

Because for Chanin, the making of an object is every bit as important as its design — a lesson that she says was driven home for her by Charles Joyner, one of her professors at NC State’s College of Design.

“Design without making is really nothing,” she says. “If you can’t make it, then it’s just an illustration. It’s an idea that has no form. I’m not saying it has no value. I’m just saying if you are a designer who wants to put materials out in the world, making is a part of that.”