Memory Serves

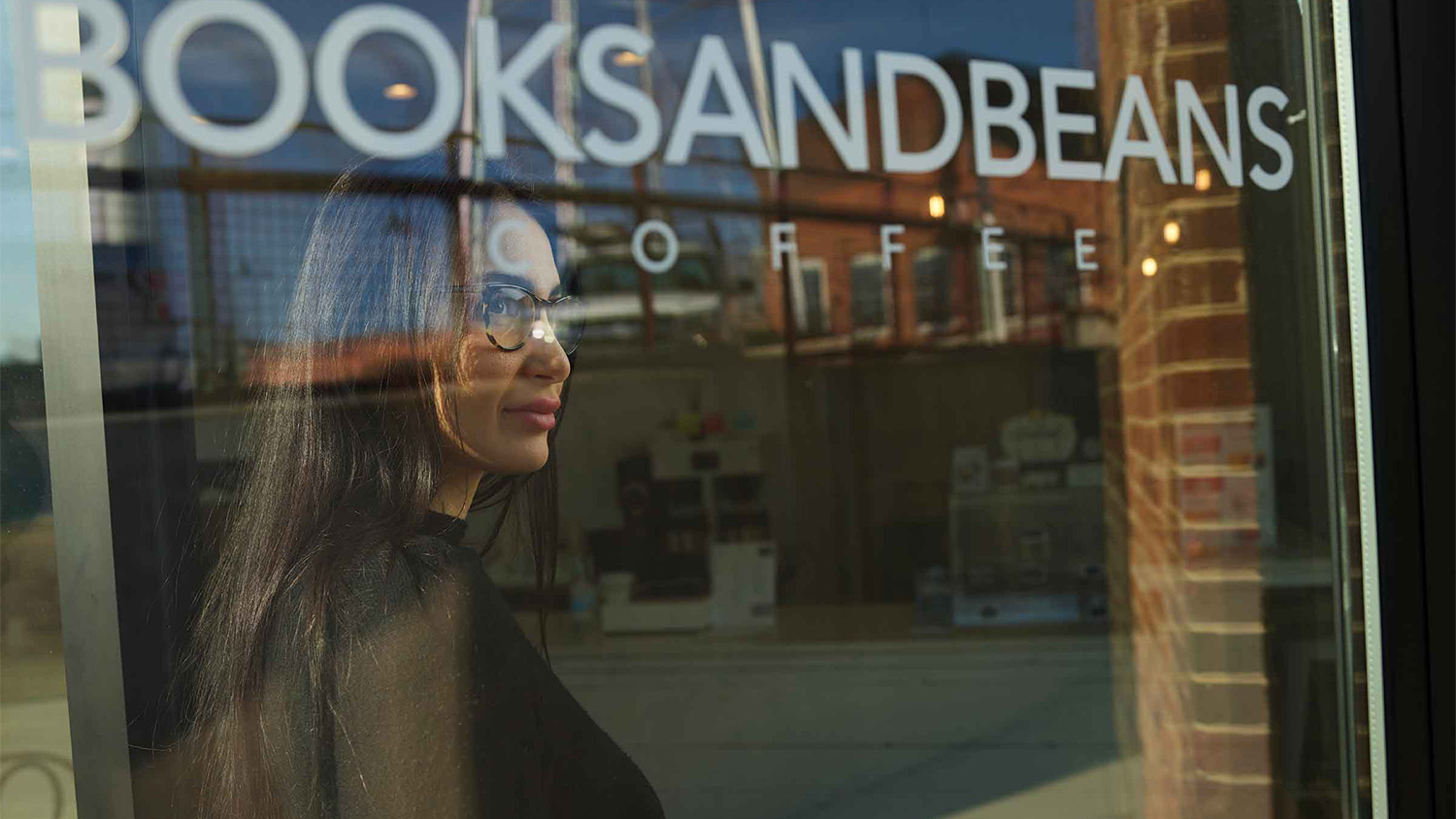

Writing unlocked a new life for Etaf Rum ’11, ’12 MA. The result was a best-selling novel that broke the silence on a taboo subject. Photography by Joshua Steadman.

ROCKY MOUNT, N.C. – The memory came flooding back that night.

It had been a rainy day. Etaf Rum ’11, ’12 MA, was taking some of her students from Nash County Community College on a field trip. Maybe it was the bus, maybe it was the rain. That night, as she began to write a journal, she remembered getting off a bus on another rainy day. She was a schoolgirl, back in Brooklyn. As her mother waited on the sidewalk, Rum and some friends waved goodbye to one another. Some were boys. When she got off the bus, her mother called her a sharmhouta — the word for “whore” in Arabic.

“I was writing down my thoughts and my memories of my early life, trying to understand why I was sad, why I could not seem to feel that I fit in,” Rum says.

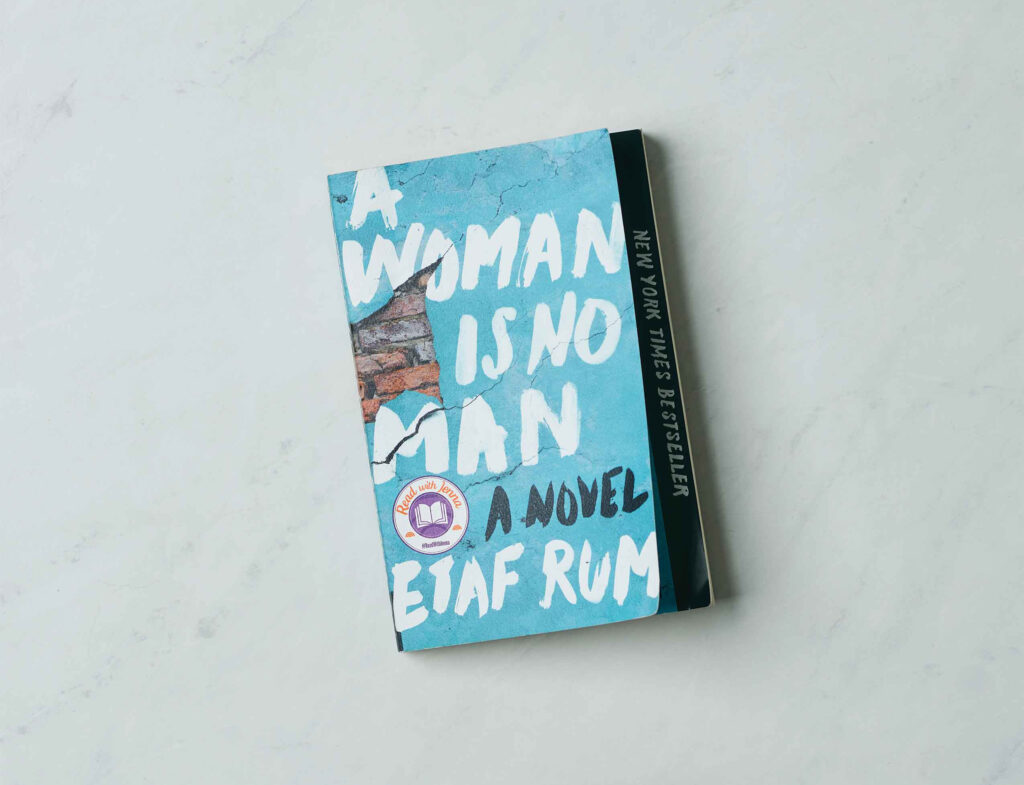

That first journal entry eventually became a scene in Rum’s 2019 novel, A Woman Is No Man, which follows three generations of Palestinian women as they navigate a culture that does not allow women many choices in life. The book and its characters are fiction, but Rum relied heavily on her experiences growing up in the Bay Ridge section of Brooklyn, where she was part of a tight-knit Palestinian community.

The novel quickly garnered accolades. The New York Times called it “a dauntless exploration of the pathology of silence, an attempt to unsnarl the dark knot of history, culture, fear and trauma that can render conservative Arab-American women so visibly invisible.” Jenna Hager Bush chose it as a selection for her book club. Rum appeared on the Today show, and A Woman Is No Man climbed to the top of The New York Times bestseller list.

The universe wanted me to have that memory in that moment, to open up all the other gates.

– Etaf Rum ’11,’12 MA

Her journey to the current moment — she is now newly married, a best-selling author about to publish her second book and owner of a popular coffee shop — began with writing down her memories. It was an act that gave Rum, 32, a release she didn’t expect. “That happened,” she says of her memories of her mother’s harsh word. “And I wrote that it happened. And it was as though God came down from the sky and into my body. The universe wanted me to have that memory in that moment, to open up all the other gates.” The memories kept coming, and she kept writing.

When she was 18, Rum began sitting with suitors in the living room of her parents’ home, serving them hot Chai tea accompanied by roasted watermelon seeds. All the young men were Palestinian-Americans whose families had approached her family.

One of the suitors, who lived in a small Palestinian community in Rocky Mount, was also a distant cousin. “Our fathers grew up together in a Palestinian refugee camp,” Rum says. “I knew him from family visits. So when his father told my father he wanted to ask for my hand in marriage, I guess I was comforted — he was not a total stranger, so in my mind I was moving to North Carolina with my family.”

But Rum had insisted on one condition. She told every suitor that she intended to continue her education, and she would not marry anyone who did not agree to that. Many of the young men wanted a wife who did nothing but take care of the home and children.

Landing in Rocky Mount was a bit of a shock. No longer surrounded by a community of immigrants as she was in Bay Ridge, she found herself missing the smells of the food and the variety of people from different cultures on the street. The Palestinian community in Rocky Mount was mostly her husband’s family, so it did not feel like her own. “And it was very clear to me that there was such a thing as an American lifestyle,” she says, “and I was not participating in it.” Growing up, she had attended an all-girls Islamic school and seldom left the house without her parents. “We didn’t hang out with Americans. The only time I ever saw them was on television.”

She was soon pregnant with her first child, a daughter, and enrolled in nearby Wesleyan College. But even with financial aid, the tuition at a private school was too high. NC State was about an hour’s drive away. She started school in 2007, taking courses online and trying to adjust her schedule so she only had to commute two days a week. “I did not have the college experience,” she says. “I was trying to get my degree and then come home and cook dinner.”

Rum thought about going to law school. But after she gave birth to her daughter, she says, her husband cut off that possibility, saying he didn’t think being a lawyer would leave her enough time to take care of their children. Rum majored in philosophy, then added English as a double-major after taking a course on 19th century American novels with Anne Baker, who remembers her as an exceptionally curious student.

“She was open to all kinds of books, really interested in what other people had to say, and interested in books as a way of imagining being in another world,” Baker says. “I did not realize until the semester was almost over that she had a family. And I did not know she was writing a novel until I saw it. But it made perfect sense.”

She was open to all kinds of books, really interested in what other people had to say, and interested in books as a way of imagining being in another world.

– Anne Baker, NC State English Professor

After getting her undergraduate and graduate degrees from NC State, she began teaching at Nash Community College. Between taking care of her two children and her household and teaching, she continued to write. “I needed to understand ways my past was influencing my life in Rocky Mount as a wife and a mother and a person,” she says. “I think I was hoping to understand some dark truth — why did I feel like this? Why did I feel so out of place in the world, and not on the path that I needed to be on?” She was teaching literature and realized she didn’t see a lot of Arab-American voices on the bookshelves. “And I began to realize that stories like mine are not there.”

At one point she enrolled in an Arab-American literature class at Duke. Then she began to think: Do I want to study Arab-American literature? Or do I want to write Arab-American literature?

Rum then knew that her journal entries were going to spark a novel.

Rum met her second husband, Brandon Clarke, in the most American of meeting spots — the gym. Their children played together in the day care at the YMCA, and the two became friends. He helped her through her struggles as she went through a separation and divorce, and the two became business partners, opening Books and Beans and two restaurants — a beer and burger joint and an artisan pizza shop — in Rocky Mount.

Rum usually talks fast with a hint of a Brooklyn accent, but she slows down for a minute and looks away when she talks about Clarke. “He’s really sweet and kind and loving,” she says. “I had never had a man treat me like a person in my own right. I was always less than, somehow inferior.” They were married in Books and Beans last year.

It has taken some time for Rum to feel at home in Rocky Mount. Even when she was teaching, she often felt like “the foreign girl on campus,” she says. But today, people know her as a best-selling novelist who owns three restaurants. “I feel like I am part of this community and I am giving back to this community,” she says. “I am not looking at it from the sidelines and wondering why I am here. Now, I see, oh, yes, I do belong here. I see the paths in my life that brought me to this moment.”

Rum’s life today includes raising her two children, ages 12 and 10, and helping parent Clarke’s 7-year-old daughter from a previous marriage. She is making sure the children know that women are never to be treated as second-best, and if she is sheltering them, it is mostly in trying to cut down on screen time and keep them off social media. They attend public school and are obsessed with Hamilton; the family recently took a trip to Mount Vernon to see history for themselves.

The title of Rum’s novel comes from something she often heard her grandmother say when, as a child, she would ask why she couldn’t do something her brothers were doing. “A woman is no man,” was the reply. The themes of A Woman Is No Man are dark — domestic violence, arranged marriage, and a preference for sons over daughters. As she wrote, she feared that she would face a backlash from the Arab-American community.

“I was worried I would be seen as a traitor,” she says. “I am talking about very taboo subjects. I have to be very careful in interviews that A Woman Is No Man is not the single story of what it means to be Arab-American.” She did receive hateful reactions on social media and in emails, but found strength in insisting that the story be told. And she found that her story connected with many women, from a variety of cultures, who had experienced domestic violence.

Although the men in her novel are capable of horrific abuse, she has also painted them as human and products of the trauma suffered by the Palestinian people. That trauma, she says, is often not acknowledged by the outside world, and it “trickles down from a political scale to a very domestic scale. From my parents who grew up in war to the way they raised me. It trickles down to the way I am with my children. It trickles down from generation to generation.

“In order to process the trauma,” Rum says, “it has to be verbalized.”

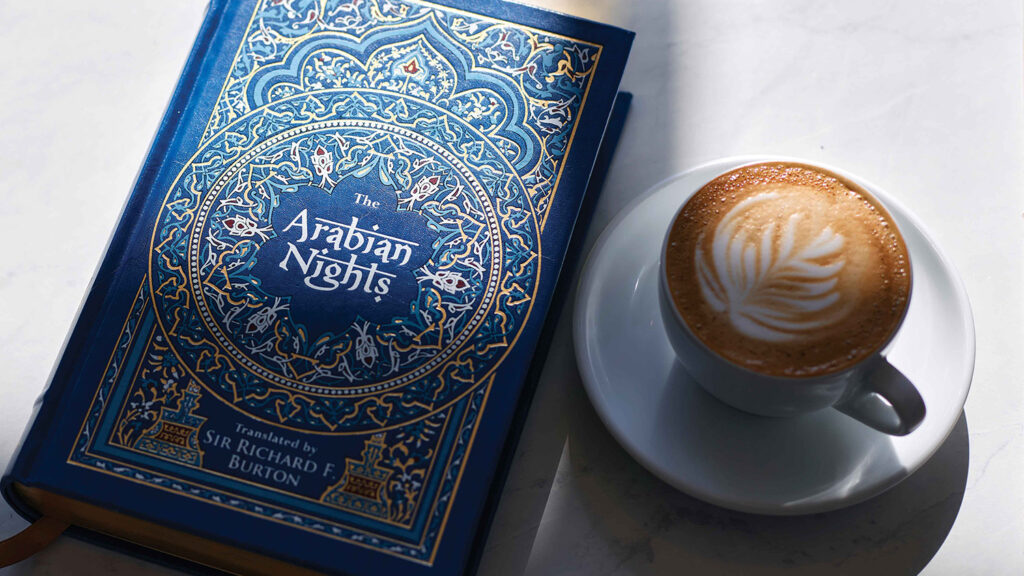

Today she sits in a chic café-cum-bookstore with whitewashed walls on the banks of the Tar River. Books are for sale along one wall, their covers displayed as though each is a treasure. Many are novels and represent diverse voices. Soon her second novel, set to be published in 2023, will join them. While her first book was set in Brooklyn and Palestine, her second novel, titled Evil Eye, is set in the American South.

In addition to the books for sale, there are used books on the windowsills, free for reading in the café. One of them is One Thousand and One Nights, a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales first written in Arabic. In the story, an evil king has discovered his wife has been unfaithful. He marries a new woman each day and kills her before the night ends. When he marries Scherezade, she decides to tell him stories — a new story each night. Stories so interesting that he must keep her alive so he can hear more the next day. It’s a book that Rum remembers as a child, and it appears in A Woman is No Man.

“It was only as an adult that I understood its power,” Rum says. “I realized that the woman in this story was literally using the power of words to save a life.” Her own life.

- Categories: