House Calls

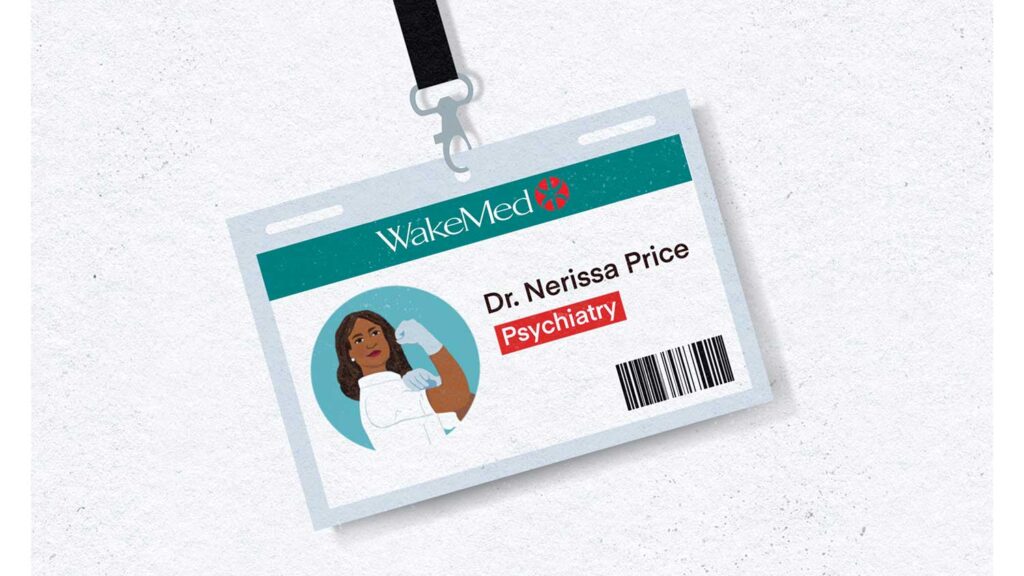

Dr. Nerissa Price ’95 and the Sister Circle started some good trouble by getting vaccines to historically marginalized communities in Raleigh. Illustrations by Laurie Allen ’17.

Dr. Nerissa Price ’95 stands inside the Garner Road Community Center in southeast Raleigh. As her memories churn and she tries to get her bearings, she has a question. Price grew up coming here; it was the YWCA when she was a child. It’s, in fact, the place where she learned to swim. So she wonders aloud, “Where’s the pool?”

The center, which serves Raleigh youth and families, has been transformed on this Saturday, as it was on many Saturdays in 2021, into a vaccination site, bustling with those who want COVID-19 vaccines and boosters, community volunteers and doctors and nurses from WakeMed. Price, a psychiatrist and a medical director at WakeMed, is brimming joyously at getting more shots in arms, something she’s dedicated the last year of her life to amid the pandemic. But she’s also here because she has a personal stake in the vaccination game. She grew up close by in the 27610 ZIP code — which is 65 percent African-American. Many residents here work low-wage and frontline jobs and have no insurance, according to Wake County.

That ZIP code also had more COVID-19 cases over the last two years than any ZIP code in North Carolina, and was among the highest per capita in the state as well.

Price, 49, sifts through her recollections about the area, leaving no doubt she’s of this place. About a 10-minute car ride from the community center is the Richard B. Harrison Community Library, the first library in Raleigh for Black residents and one of Price’s favorite childhood retreats, where she could get lost in Nancy Drew and Judy Blume. And there’s New Bethel Christian Church, where she got to witness the virtuoso of the pastor’s wife on organ.

For the last two years, Price has been at some of those same places when they served as community vaccination sites. Early on in the pandemic, it became evident that this area was not only the hardest hit with cases, but was also lagging in its vaccination rates. So Price, along with five other Black women doctors — a group that called themselves the Sister Circle — mobilized to help with the Triangle’s vaccine effort in Black and brown communities, running COVID-19 vaccination sites on Saturdays. Price went door-to-door with WakeMed’s Doses to Doors program. She reached out and visited with homeless people to get them vaccinated. And she even administered shots herself. As of this spring, the Sister Circle has helped get some 15,000 shots in arms in Raleigh.

He told me, ‘You know, Nerissa, a lot of times people look far away for need, but there’s plenty of need in our backyard.’

Mo Johnson ’94, CEO and senior program director at the community center, calls Price “the Sojourner Truth of southeast Raleigh when it comes to vaccinations.” “We needed someone to come to our neighborhood and do this,” she says of Price and the Sister Circle. “I don’t think they wanted to leave this to chance or hope. They decided, ‘We are going to do this another way. We are going to the people.’”

When Price reflects on the 27610 ZIP code against the backdrop of COVID, she recalls the words of her medical school mentor at UNC, also an NC State grad. “He told me, ‘You know, Nerissa, a lot of times people look far away for need, but there’s plenty of need in our backyard.’”

Coming Full Circle

The beginnings of the Sister Circle — which also includes a pediatrician, two OBGYNs, a primary care doctor and an obesity medicine specialist — stretch back further than the COVID-19 vaccines. Dr. Rasheeda Monroe, a pediatrician and medical director at WakeMed, says the women came together a few years back to establish a network of Black female colleagues who could share experience from their own careers. “Some of us had experienced some tough times, just as Black women physicians, and navigating what it looks like to be in an environment where hardly anyone else looks like you, and certainly not in leadership,” Monroe says.

Then COVID-19 came along. “And then, on top of that, George Floyd,” Price says, citing another seismic cultural moment from spring 2020. “So then there were unique issues that were intertwined with COVID and racial justice that we started to reach out to each other to talk about, kind of in an uncensored sort of safe way.”

“We needed someone to come to our neighborhood and do this. I don’t think they wanted to leave this to chance or hope. They decided, ‘We are going to do this another way. We are going to the people.’ ”

— Mo Johnson ’94, CEO and senior program director, Garner Road Community Center

Just as potent as their conversations was what the Sister Circle saw — or didn’t see. At the outset of North Carolina’s vaccination efforts in the latter part of 2020 and the beginning of 2021, Price and her colleagues were ecstatic that the vaccine was becoming available. Then came the vaccine events WakeMed held. Price remembers a drive-thru event early on: “Rasheeda Monroe noticed that there was very low Black and brown representation. And so she immediately kind of asked the question to leadership, ‘What are we doing specifically to reach out to Black and brown communities?’”

‘You Just Survive in Your Zone’

For much of North Carolina, vaccines were seemingly ubiquitous in 2021. But that wasn’t the case for some historically marginalized and rural communities. Price points out that many jobs don’t have paid time off or sick time, so showing up at a site between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. may not work. But let’s say it does. Transportation can also be a barrier. And even getting signed up can be difficult for people who have no broadband or don’t have a computer. And older residents may not know how to navigate the Internet to find an online portal to register.

All of these issues were at play, Price says, in the areas that make up the 27610. “For some people, they live within these completely separate segregated communities. You function in that community. You’d never go over to the other side of town. You don’t even know what they have to offer over there. You just survive in your zone, like that’s your world. So how do you even get access to the person to tell you, ‘Oh, there’s another world over here’?”

Then there’s the skepticism in Black and brown communities directed at medicine. Lechelle Wardell, COVID-19 community outreach and engagement manager for Wake County Public Health, says that while the older population was more open to vaccinations, hesitancy was palpable in the younger population during vaccine outreach. She says their generation has grown up studying and reading about research projects on minority communities such as the Tuskegee syphilis study and programs like eugenics. “And we were also in the middle of Black Lives Matter,” Wardell says. She says she began to encounter a sentiment among young people that they felt, “‘this is another example of the government, white folks trying to kill us off. We’re not going to get it.’”

The Sister Circle’s goal became ensuring that vaccines would get to marginalized communities and establishing themselves as trusted voices. The Sister Circle, all of whom had been vaccinated, went to the leadership at WakeMed and asked for some doses to be held for Black and brown communities at an event. Price says after some prodding, WakeMed initially provided 300 doses.

“Within days — I’m talking like a handful of days — I had 700,” says Monroe, who points out they had to prove the need just to get institutional buy-in. “. . . We ended up getting a lot of support from the county and our health system and the community, but not initially. And so we were pulling up a chair to a table that we hadn’t been invited to, and we were advocating for people who often are lost in the conversation.”

Good Trouble

The Sister Circle and Wardell, who called upon all the relationships she’s formed in 26 years of working in Wake County, continued their efforts and found 17 community partners in the 27610 ZIP code. They worked with Latino churches, mosques, and the Guatemalan and Mexican consulates to establish partnerships. They utilized bedrocks of the Black community — fraternities, sororities and churches, like Word of God Fellowship Church, Macedonia New Life Church and New Bethel Christian Church, where the sanctuary served as a makeshift vaccination clinic.

Once that connectivity was in play, the Sister Circle hosted vaccination clinics on Saturdays, often wearing shirts bearing the words “Good Trouble,” the mantra of the late congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis. Going door to door to give vaccines, Price found a receptive audience. “It wasn’t people who were really asking me lots of questions,” Price says. “It was like, ‘Thank God you’re here.’”

All those shots helped move the needle statewide. “We were getting some data, too, from the state, which was telling us that, you know, ‘Whatever you guys are doing, keep doing it,’ because they were noticing the vaccination rates, after each event, were improving by like 1% for the entire state,” Price says.

What sticks out most from those door-to-door visits were the connections she formed. Sometimes, one shot led to more. There was a 16-year old girl, the first vaccinated in her family, who convinced her mom to get the shot on the same visit, and then convinced her dad to get the vaccine on another visit from Price. Another person reached out to Price to see if Price could get a booster to her homebound mother. Sometimes, it was just listening to their stories — and offering tangible help. “Oftentimes, in medicine . . . the role is just to listen and to be there to comfort them. But this went another step further,” says Price. “This was like, ‘And with this shot, I can help protect you. I can help change the realities that so many others around you who are dying from. I can help save you from this.’ ”

Price is effective at reaching people and convincing them to get the shot, Wardell says, because she employs a personal approach instead of a clinical one. To call Price’s constant smile bright is fair but also undersells its beam. There’s warmth in her voice, not the cold sterility of a doctor’s office room. “She is able to encourage and explain and address people’s concerns and hesitancies about COVID, about the vaccine, in a way that makes sense to them,” Wardell says. “And when she goes out, the population, they truly believe she cares about them.”

Before the pandemic hit, Price was experiencing a little of the burnout that can come with the territory of being a doctor — are you truly helping patients? Then there’s the burnout that comes from trying to illuminate health inequities. Price at times felt like a “lone voice in the wilderness kind of thing.” But COVID-19 taught her that being a Black health care provider doesn’t mean she has to carry that load by herself.

“Just being with these other women,” Price says, “that then also spread to other doctors — Black and brown at first, but then also our white colleagues, and across not just WakeMed but also UNC and Duke, you start to realize you’re not alone.”

- Categories: