Black Bird, Fly

Birder Deja Perkins ’20 MS helped launch a social media movement with the message that Black naturalists belong and are here to stay.

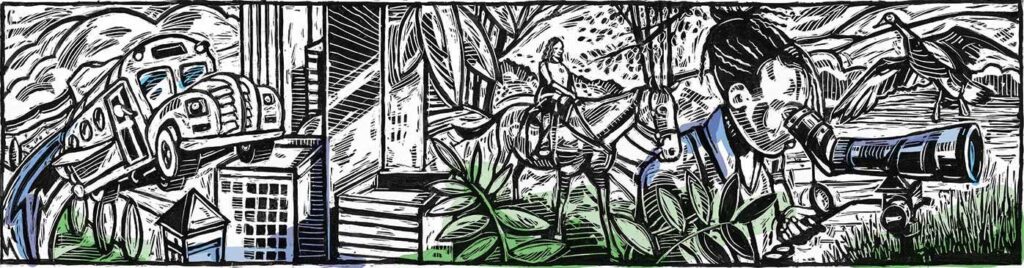

Illustrations: Gary Palmer

In May 2020, urban ecologist and avid birder Deja Perkins ’20 MS was working to finish her master’s degree in the College of Natural Resources, when she was confronted with the moment that would be the impetus for #BlackBirdersWeek, a vibrant social media movement that began last summer and celebrated Black naturalists and their place in the outdoors. The moment came via video on her phone.

Some of Perkins’ Black STEM colleagues dropped a video in their GroupMe chat. And with a click, they watched a scene from Central Park in Manhattan. Perkins watched as a white woman handling her cocker spaniel walked toward a man filming her with his cellphone camera and asked him to stop recording. (It would come out later that the woman’s dog had been unleashed and a birder — the one filming the incident — had asked her to put the dog back on the leash, which Central Park requires.) The white woman was Amy Cooper, and the birder was Christian Cooper, a Black man. Perkins continued to watch as the woman said she was going to call the police and “tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life.” The man told her to go ahead and call the police, which she did. “There is an African-American man — I’m in Central Park — and he’s recording me and threatening myself and my dog,” the woman told the dispatcher.

“As I watched it, I was like, ‘Is she serious?’” says Perkins. “. . . Our public lands are supposed to be public lands for all of us to enjoy.”

No More Rare Birds

For Perkins, 25, and other Black naturalists around the country, the video illustrated the racism built into the notion that Black people rarely engage with or don’t belong in nature, that the outdoors is a white world. In his memoir The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, one of Perkins’ go-to reads, Black birder and conservationist J. Drew Lanham writes, “I am as much a scientist as I am a black man; my skin defines me no more than my heart does. But somehow my color often casts my love affair with nature in shadow. Being who and what I am doesn’t fit the common calculus. I am the rare bird, the oddity: appreciated by some for my different perspective and discounted by others as an unnecessary nuisance, an unusually colored fish out of water.”

Myron Floyd is the dean of NC State’s College of Natural Resources and researches environmental justice and how race and ethnicity are involved in leisure activity choices. He says one reason that Black people are perceived, wrongly, as a rarity in the outdoors is because of a persistent American myth. “One strong idea is the rugged idealist. A man. Usually white and you’ll go out and conquer nature. It’s an ideal,” says Floyd. He says that Black people who engage with nature have been overlooked in the past. Now, he says, “there’s a new narrative.”

Perkins, a community engagement specialist at NC State, is at the forefront of that new narrative.

That includes a growing visibility of people of color taking in the natural world with hiking, camping, birding, fishing and other activities. Perkins first felt that pull to the outdoors growing up on the southeast side of Chicago, Ill. She had her backyard and a nearby park, but that was about all the green exposure she had. “I had the Magic School Bus set,” she says. “I would be transported to another world. There was always a desire for me to be outside. I wanted to go horseback riding and travel to do the things I read about in the books. But there wasn’t really the space for that in the city.”

I had the Magic School Bus set. I would be transported to another world. There was always a desire for me to be outside.

— Deja Perkins

Perkins and her family — especially her grandmother and great aunt — found their spots, though. There was Lake Shore Drive, where Perkins remembers seeing geese glide in the air and calling them “my babies.” There was Wolf Lake. “We’d drive around and we would see these blue herons flying around,” Perkins says. “I just remember being so amazed.”

Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium and the Museum of Science and Industry, where she was transfixed by dinosaur exhibits, were both stops. Her mother enrolled her in educational programs where she could become a beginner naturalist. “Being able to see the skulls and the different things to engage with,” she says, “. . . I felt like I had found my purpose. It was the first time I found community in science.”

But with that came another realization. “I was the only little Black girl there,” she says. “But I didn’t let that stop me.”

For the Birds

When Perkins is on a walk leading a group looking for birds or leading an online program, she starts out sounding like a teacher with an informative tone. As she describes birds, though, she becomes energized as a joyous smile breaks wide across her face. She talks about them as if she’s telling you about her best friends. She calls wood ducks “some of the most beautiful of North American birds.” She says woodpeckers are some of the most enjoyable birds to see. She advocates for pigeons and doves, proclaiming, “They deserve their own spotlight.” She prefers towhees to robins (She’s wary of robins, in fact, calling them “CIA birds.” “They’re everywhere, and they’re always following you.”). She imitates the towhee’s call: “Drink your tea,” she says in a high-pitched chirp. “Drink your tea.”

Perkins originally set out to pursue being a veterinarian at Tuskegee University in Alabama, where she saw Black veterinarians for the first time. A student conservation program landed her in Bloomington, Minn., at the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge, where she started to be wowed by birds. She saw for the first time wild turkeys, red-tailed hawks and a juvenile Cooper’s hawk land on a bird feeder and try to hone its hunting skills.

Shifting her focus away from becoming a vet, Perkins began to build on that new interest in birds. During a year at Mississippi State University, she got to work with professors monitoring red-tailed hawks around Starkville, Miss. She studied whether double-crested cormorants were eating fish off the top of catfish ponds. She worked on a project examining whether egrets could transmit bacterial disease. “It was me being introduced to human-wildlife conflicts,” she says. That interest is something that continued in Perkins’ graduate studies at NC State, where she worked in the Lab of Reconciliation Ecology, which focuses on the intersection of ecology, people and local communities. It includes the Triangle Bird Count, a study of bird species across locations.

Black In Nature

While leading an online session for the Duke Gardens Adult Education program in November 2020, she mentions a fundraising effort with a majority of the proceeds directed toward encouraging more Black people to experience the outdoors. The shirt for sale features three black bird heads on the front, and on the back reads, “Black birds are often accented with bright colors or iridescence, making them one of the most stunning species.”

“We,” Perkins says, speaking of herself and fellow Black naturalists, “are sometimes undervalued, just like black birds, in the birding community.”

Her undergraduate year at Mississippi State was a “culture shock.” Starkville was a different world to Perkins, who had attended an all-Black high school in Chicago, as well as Tuskegee, a historically Black university. “I had been surrounded by Black people my whole life,” she says. One semester, in a class, her assignment was to create a specimen, which could be dressing a skull or a dead animal. She wondered where she was supposed to get a dead animal. Perkins says her professor replied she could go hunting or pick one up from the side of the road. She worried about her general safety as she thought about walking along a country road, not to mention her concern that residents and police might question what she was doing. Such issues, it seemed, hadn’t crossed the professor’s mind.

A year later as a graduate student at NC State, an adviser introduced Perkins to the BlackAFinSTEM Collective. (The “AF,” for those who haven’t seen the Netflix show with a similar name, serves as a pronouncement of just how proud one is to be Black.) She soon became part of this online community, with some 100 members, 15 or so who are birders.

“Part of it was an affirming space,” she says. “A place to kind of talk about some of the issues I was having in grad school. It was a place for me to talk about wanting to go outside and having people I wanted to talk to. I could post a picture, and there would be other people who would get excited.”

The group also meant she had people to grieve with. It provides her a retreat when she is made to feel an outsider. Like the time Perkins was conducting field work near a woman’s home, and the woman told Perkins she wasn’t comfortable and brought out her dog. Or the time last fall when she traveled to western North Carolina to visit one of the state’s national forests, and a fast-food drive-thru attendant said, “You’re a long way from home.”

And the BlackAFinSTEM Collective was there for her that day in May 2020 as she viewed the Central Park video. Perkins remembers the incredulity she and others felt watching the video that evening. Then her mind jumped to Christian Cooper’s welfare. “I kept wondering what happened afterward, was he OK,” she says. Some in the BlackAFinSTEM community who knew Cooper confirmed he hadn’t been harmed or something worse, a concern with the deaths of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery fresh on everyone’s mind. “[W]e were happy that he was safe and not another name to put on a list.”

The members of the BlackAFinSTEM group started texting and talking, and the idea was discussed that the group engage in a weeklong endeavor to highlight and celebrate Black birders. And with that, Perkins was a co-founder of #BlackBirdersWeek.

The week, which ran from May 31 to June 5, was built around social media posts and daily hashtags that were calls to action. There was #PostABird Challenge, #AskABlackBirder, a #BirdingWhileBlack livestream discussion, and #BlackWomenWhoBird. And Perkins’ favorite: “I think #BlackInNature was the most important,” she says, “and the one we still have today.”

The hashtags surged, with thousands of impressions on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The National Audubon Society and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service used the hashtags in posts and shared stories from Black park rangers. The movement was featured in Scientific American and on CNN. And, Perkins says, the campaign also led to numerous partnerships, like the one with the online company Animalia for the black birds shirt. Organizations like the Association of Field Ornithologists offered free memberships to Black children interested in birding.

You create a spark in someone like Deja. She comes back. There’s something there that can have a longer term impact in that community for her career and others like her.

— Myron Floyd, dean of NC State’s College of Natural Resources

For Perkins, the future holds many places over which she wants to soar. She and the BlackAFinSTEM Collective, of which she is currently president, wrapped the second annual #BlackBirdersWeek in June. Costa Rica remains on her birding bucket list. On the home front, she’s getting to know the barred owl she recently discovered living near her apartment “Whoooo cooooks for youuuuuuuu?” she imitates its call. She continues outreach and mentoring with her lectures and programs today.

Floyd says such mentorship is invaluable, suggesting mentors pave the way for kids to stay involved into adulthood. “You create a spark in someone like Deja. She comes back. There’s something there that can have a longer term impact in that community for her career and others like her.”

Perkins hosted bird walks for the City of Raleigh this past spring, and she still gives talks online about birds and her experiences with #BlackBirdersWeek. In December, she gave an online presentation to the Connecticut Audubon Society titled “#BlackBirdersWeek: The Hashtag that Started a Movement.” After it was over, a father tweeted at her, “Thank you for the presentation in #ctaudubon. It was really great and eye opening. It was a lesson for my 9 year [sic] old too.”

It’s moments like those that show what the #BlackBirdersWeek movement she helped start and grow has given Perkins: the power to be seen. “#BlackBirdersWeek,” she says, “gave me the platform to have my voice heard.”

That, Floyd says, can lead to others then joining in. “We have Deja,” he says. “She saw someone that inspired her that she could do this and be a part of this. It also gives you the resolve or the will to continue and to claim your space in this. The more that happens, the more others will see it and resolve to do the same.”

- Categories: