First in Their Pack

NC State helps pave the way to success for first-generation students. Illustrations by Gary Palmer. Photographs by Marc Hall.

Jackie Gonzalez ’18 was a high flyer at her high school in Lincolnton, N.C., a former textile town three hours west of Raleigh. Outspoken and precocious, she and her large group of friends took turns holding the highest positions in student government, and her competitive nature pushed her to excel in her classes: “If my friends were doing something, I was like, ‘I’ll do better,’ ” she says. Her parents, who had come to North Carolina from Costa Rica in the 1990s, hadn’t gone to college. But they instilled in Gonzalez that a college degree was the key to her future. Her counselors pushed her to take every Advanced Placement class her school offered — sometimes against her protests —and to apply to Harvard and Yale as well as North Carolina universities. With a love of politics that began while watching news shows in Spanish with her parents, she figured NC State would be a good place to study political science, though she never visited campus until the first day of orientation.

When she got to NC State in 2014, she hit a wall. A 44 on her first test in political science, her planned major, made her consider dropping out. A dipping GPA disqualified her from the University Scholars honors program. Tears and anger led to a frustrating conclusion: “I realized it wasn’t just this course or that professor,” Gonzalez says. “I just didn’t know how to college at all.”

Gonzalez learned “how to college” and got back on track. She graduated in 2018 as student body president, and now works as development director for a nonprofit and plans to go to graduate school. But research shows that students whose parents don’t have college degrees often fail to complete their own degrees, a gap that colleges and universities are increasingly trying to fill with programs aimed at supporting first-generation students. In recent years, NC State administrators have sought to keep the university’s roughly 4,000 first-generation students on track to graduate in a variety of ways, from fostering a sense of community to connecting students to various services and mentors.

Almost a quarter of college-bound high school sophomores in 2002 were the first in their families to attend college, according to a national study by the U.S. Department of Education. A decade later, only 20 percent of these so-called “first-gen” college students had earned degrees, compared to 42 percent of those whose parents had college degrees. The reasons are as varied as the students, though there are common themes. They tend to come into college less prepared than their peers, from high schools that offered fewer Advanced Placement and upper-level math courses. They often come from lower-income homes and struggle financially; money is the number one reason cited by first-gen students who don’t earn a degree, including both the cost of tuition and the need to support themselves. Finally, those students often experience confusion over academic requirements and expectations and have a reluctance to ask for help.

The stakes for success are high, as a college degree continues to be key to upward mobility. The median annual earnings of a high school graduate in 2017 was $35,600, while it was $58,650 for a college graduate, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a difference of more than $20,000 a year. “We all know that higher education is a transformative experience. It changes your trajectory,” Chancellor Randy Woodson says. “The change in trajectory is most dramatic for a student that comes from a family with no higher education experience. … It affects everything. It affects your longevity. You live longer. You’re healthier, which is tied to your ability to support yourself. You’re less likely to be in prison. I mean, all sorts of social issues are changed by going from a family that’s never had a college experience to one that does.”

“First in the Pack”

NC State has welcomed first-generation college students throughout its history — from the children of farmers, merchants and mechanics who flocked to Raleigh in its early days to the returning soldiers who, thanks to the G.I. Bill, were part of a nationwide explosion in college degrees after World War II. But the term has become an educational buzzword in recent years, as colleges and universities have begun to consider first-generation status in admissions and programs. In each of the past five years, NC State’s freshman class has included anywhere from just over 600 to nearly 800 first-generation students. In the fall of 2018, they made up about 15 percent of 4,800 incoming freshmen. An even larger percentage of transfer students are first generation.

Educating first-generation college students has always been part of the mission of public, land-grant institutions like NC State, says Jon Westover, director of admissions and himself a first-generation college graduate. “They’re certainly a group of students that we want to make sure have opportunities to come to NC State,” he says.

Courtney Simpson ’05, ’08 MED was the first in her family to earn a college degree and now runs NC State’s programs for first-generation students. She urges students to embrace their distinctive role, even if it comes with challenges. “It’s not a negative connotation but one of pride,” says Simpson. “If you can teach students to be prideful in who they are and their story, they’re more likely to succeed.”

“If you can teach students to be prideful in who they are and their story, they’re more likely to succeed.”

— Courtney Simpson ’05, ’08 MED

Simpson never heard the term “first-gen” when she was an undergraduate at NC State, but she recognized she needed help in ways that differed from many of her classmates. Like Gonzalez, she was surprised by the difficulty of her classes, but was embarrassed to seek help from a tutor or counselor. She was also going home to Johnston County, N.C., every weekend to work at Dairy Queen — taking time away from her studies. During her first week, she was so intimidated by one of her large communications classes, she called her mom to pick her up and bring her home. The next day, her mom insisted on bringing her back. “Which was one of the best things that she probably could have ever done for me,” Simpson says, “because what that told me was, ‘Yes, you always have a place where you can call home, but you have to do this. There are no ifs, ands, or buts about it, you absolutely have to do this.’”

Simpson says she was lucky to find mentors who eased her homesickness, connected her with tutors and maybe most importantly, encouraged her to get a job on campus. Now, it’s part of her job to help level the playing field for current students. She heads a series of programs for first-generation and low-income NC State students launched in 2016 through the federally funded TRIO program. Students are connected with tutors and mentors and are invited to a series of events to help them succeed in class and in the workforce. In January, for instance, the daylong Nav1gate Summit gave students a chance to connect with other first-generation students and staff, and to explore their strengths to create a college success plan. TRIO staff also encourages students to look beyond class and work to experiences such as undergraduate research and studying abroad, which are valued by employers but often eschewed by first-generation students who are so laser-focused on earning a degree that they often fail to explore those opportunities.

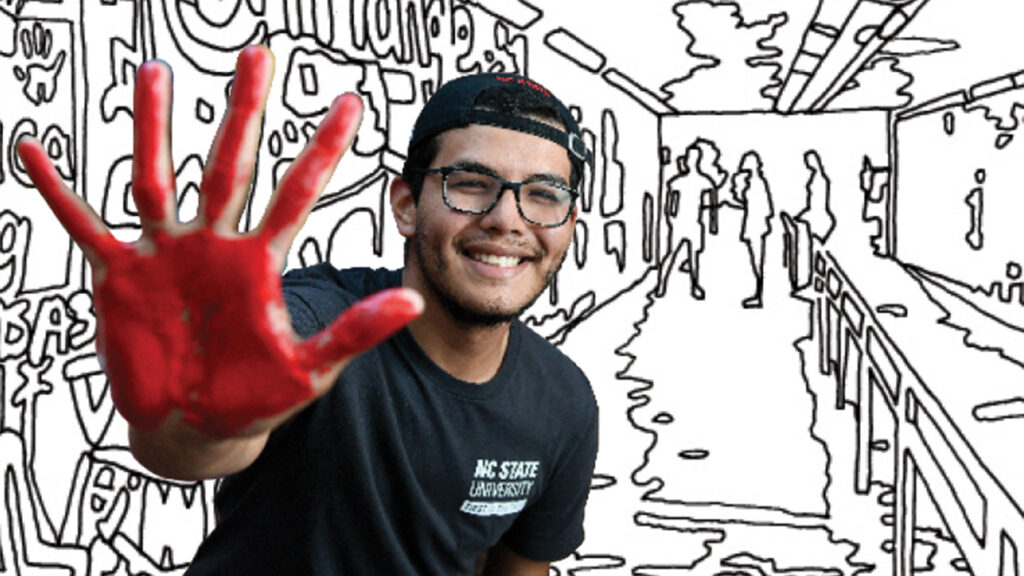

Another segment of TRIO programming seeks to immerse students in the Wolfpack culture. First-generation freshmen are welcomed with a “First in the Pack” event in the fall, and receive lapel pins that spent a night in the Bell Tower — an initial bookend to another tradition (seniors’ class rings also spend a night in the tower). During another event, first-generation students are invited to add their names and handprints to the Free Expression Tunnel. Such rituals might seem small, but studies show students who feel connected are more likely to finish their degrees. “What they need for the long term is a sense of community and belonging,” says Simpson. “That’s what gets our students to stay here on campus, to persist and complete their degrees.”

Only 20 percent of first-generation college students earned degrees within 10 years, compared to 42 percent of those whose parents had college degrees, according to a national study by the U.S. Department of Education of college-bound high school sophomores.

Finding Their Way

For Alston Willard, a senior from Zebulon, N.C., who majors in ecological engineering, finding his way at NC State was partly about overcoming culture shock. NC State was the only school to which he applied, though he never visited the campus. Once in Raleigh, he met people who had kept spreadsheets of their potential colleges and hired writing coaches for their application essays. He met people who were wealthy in ways he had never seen, and who seemed to feel exceedingly comfortable with college life. “A lot of the kids seemed like they were bred for college,” he says. “I felt like I was just lucky to be going to college at all.” Coming in without taking calculus, he also felt behind his peers in class. He says his sophomore year was his “crucible”; he was scraping by in physics, and taking on a lot of debt because he couldn’t find time to work. He lost 10 pounds, but he learned to study hard, and early, for tests, and spent hours with tutors and online tutorials. Now he has friends who were blindsided by the higher-level classes in their majors, while the study skills he’s honed are paying off. “It’s been hard for me since I got here,” he says. There were other hiccups. A scheduling snafu tacked on an extra year to his degree; he’ll graduate in 2020 as a fifth-year senior. But he also took a risk and studied abroad, taking hydrology and waste management classes in Belgium — a life-changing experience he had never imagined having.

While Willard found his own path to success, Jean Ferman says TRIO helped make the connections he needed to feel at home. A junior from Raleigh majoring in biology and chemistry, he says his parents were supportive when he went to college. But they didn’t have the knowledge of how college works that might have helped him. “I was the type to do everything on my own and I tried to do that my first semester at NC State but it was too hard,” Ferman says, recalling his own first failing grade: a 38. “My parents said, ‘You went to college and you can do anything,’ where other parents might have said, ‘Have you talked to your professor or adviser?’” He got involved with TRIO, which connected him with services and helped him take a trip to South Carolina and Georgia to visit graduate schools and learn more about applying. He got involved with a working group on first-generation students within student government, and helped found F1rst at NC State, the university’s first student-run organization for first-generation students. F1rst plans to hold seminars and social events this year to connect first-generation students and make sure they’re aware of what’s available to them on and off campus. “They do not have to go through this time by themselves,” Ferman says.

Hillary Sudbury, a 40-year-old mother of two from Clayton, N.C., found tutoring help and much-needed moral support through TRIO as she juggled child care, commuting and challenging courses. Like many first-generation students, she is taking an untraditional route to her college degree: starting community college to become a teacher’s assistant, and at one point studying to be a hairstylist, before heading to NC State to study civil engineering. “When I found TRIO, I knew that would help me stay motivated when times got tough,” she says. Her father founded a commercial construction business and never encouraged his children to go to college, she says. But she expects to send a different message to her own children, now 11 and 13, when she graduates, she hopes, next year: “I think they’ll see that you may struggle, but there’s always a way.”

For Gonzalez, it was her own persistence that helped her succeed. When her GPA fell below the requirements for the University Scholars program, she wrote a letter asking to be readmitted and worked hard to raise her grades, even rewriting several papers. She also started working closely with the head of the political science department — the same professor in whose class she had earned that first failing grade — who got her interested in classes focused on political polling. “I met professors I liked and started working with them,” she says. “That’s when it sort of clicked.” Eventually, a friend persuaded her to run for a seat in the student senate. She won that seat and later was elected student body president. As president, she focused on the needs of first-generation students through a student-led work group that helped lead to the creation of the F1rst at NC State group. Looking back, she wishes she hadn’t doubted herself in her early days at NC State. “I would tell any student now to just find that confidence,” she says. “Just know that you may be the first in your family, but you’re not the first person to do this.”

This story originally appeared in the Autumn 2019 issue of NC State magazine.

Tell Us What You Think

Do you have a personal connection to this story? Did it spark a memory? Want to share your thoughts? Send us a letter, and we may include it in an upcoming issue of NC State magazine.

- Categories: