At the Top of Her Game

Angela Medlin ’91 broke down barriers to become a rock star in the world of fashionable athletic wear. Now she’s opening doors for the next generation of designers. Photography by Jon Jensen

by Sharon Overton

Angela Medlin ’91 takes the stage in Portland, Ore., in high-heeled boots and a sleek black dress slung casually off one shoulder.

The auditorium is packed with creative professionals who’ve come to hear a series of talks by local leaders in the worlds of design, film and publishing. On the big screen behind her are logos for the high-profile brands where Medlin, 51, has made her mark: Adidas, The North Face, Levi’s, Eddie Bauer, and most recently as design director for Jordan apparel at Nike.

Medlin clicks to an image that seems out of context in this hip, urban setting. It’s a photograph of a run-down shack in the rural south, with broken windows, a sagging front porch and a hen-pecked yard. The picture is “almost identical” to the four-room house in Hamlet, N.C., where she lived as a young girl, Medlin says. The house had no running water or indoor toilet. The walls were stuffed with newspapers for insulation; if you poked your finger through the paper, cold air blew in.

But within those walls, she says, Medlin flourished in an atmosphere of “total creative freedom.” Her grandparents and teenage mother encouraged her love of drawing and design. They bought her pencils and notebooks from the feed store, and she filled page after page with sketches of faces, figures and Barbie doll fashions. When they didn’t have money for art supplies, she says, “they gave me a wall to draw on.”

Her family gave Medlin the courage to believe she could accomplish whatever she set her mind to. She’s applied it to her work, from designing urban tees worn by hip-hop icons to helping Air Jordan once again take flight in the mid-2000s. And it’s the message she now brings to her Portland audience, and as a mentor to the next generation of aspiring young designers: Don’t let your dreams be limited by your circumstances. “Whatever box you put yourself in, or somebody else puts you in,” she says, “smash the box.”

“Whatever box you put yourself in, or somebody else puts you in, smash the box.”

– Angela Medlin

A Badass “Design Mom”

Wedged between a coffee shop and an artisan leather store in Portland’s edgy Old Town, the Pensole Design Academy is a long way from that four-room house in Hamlet. Described as the world’s first sneaker school, Pensole attracts dozens of promising design students from around the globe who gain real-world experience tackling projects for industry sponsors such as Under Armour, New Balance and Adidas. Classes range from multi-day skills-building workshops to an accredited 12-week design intensive in partnership with the Pacific Northwest College of Art.

Medlin joined the faculty in 2017 as founder of the Functional Apparel and Accessories Studio. She describes functional apparel as “an extension of the body. It’s apparel that gives athletes their superpowers. It enhances performance to push bodies beyond their natural limitations. It’s the product that keeps everyday consumers cool, warm, dry, comfortable and protected from inclement weather.”

The idea for the studio came out of a serendipitous meeting with Pensole creator D’Wayne Edwards, a celebrated sneaker designer and fellow Nike alumnus. After nearly three decades designing for the world’s leading activewear brands, Medlin was ready to share what she’d learned. Edwards saw an opportunity to expand the school’s curriculum beyond footwear to include a full range of functional clothing and accessories. “She is a talented designer with an amazing career history,” Edwards says. She’s also a “natural mentor and teacher.”

Pensole feels like a cross between an industrial trade school and a high-tech start-up. In the cavernous footwear studio, students ranging in age from their late teens to early 30s lounge on black leather furniture or slouch behind laptops at long wooden tables. Like the student body, the “dress code” is decidedly diverse — from ripped jeans and hoodies to high-end athletic wear. On one wall, prototype sneakers are displayed like futuristic works of art. An upstairs workshop is filled with industrial sewing machines and bins of brightly colored leather and synthetic fabrics.

By contrast, the vibe in Medlin’s apparel and accessories studio across the hall is calm and uncluttered, with white walls and minimalist modern furniture. She calls it her “Zen den.” On a fall morning, a handful of students gather on a large sectional sofa to offer each other feedback. About a third of the way into the 12-week session, they’re already neck deep into design projects ranging from protective head gear for female soccer players to a wearable shelter for people living on the streets. Giant storyboards covered with their sketches and design inspirations line the walls.

Simone Bakke, a 28-year-old graduate student from Copenhagen, discusses her early concept for the soccer helmet. A young woman in a black motorcycle jacket says Bakke’s design reminds her of an “old-school football helmet” and wonders if teenage girls would actually wear it. Medlin poses a question: Is there a way to make the wearer feel both beautiful and powerful? “Like a crown,” she suggests. A tall young woman in a gray hoodie jumps on the idea. That’s “so badass,” she says. “Think Wonder Woman.”

“Badass” can also describe Medlin herself. Compact and soft-spoken with the slightest trace of a Southern accent, she dresses mostly in black and keeps her platinum curls closely cropped. On a recent day, she wears a hooded fleece tunic and leggings with bright red sneakers, matching lipstick, and bold cat-eye glasses, bringing to mind a mashup between Marilyn Monroe and a hip-hop monk.

In the classroom, Medlin can be funny and encouraging, but also tough. She wants students to get a realistic idea of what it takes to be successful in a highly demanding and competitive industry. Students are assigned to cross-disciplinary teams, just as they would be at real companies. They work on tight deadlines and are expected to behave professionally, which means “showing up on time and doing more than you’re asked.”

They get regular feedback from industry sponsors, who sometimes subsidize tuition, which runs roughly $11,000 per session. At the end of the session, teams present their work to sponsors and faculty, and it’s not just a grade that’s at stake. Since Pensole opened in 2010, more than 250 students have been placed in jobs or internships with footwear and apparel companies around the world, according to the school. “This is essentially a 12-week interview,” Medlin says.

“She is a talented designer with an amazing career history. She’s also a natural mentor and teacher.”

– D’Wayne Edwards

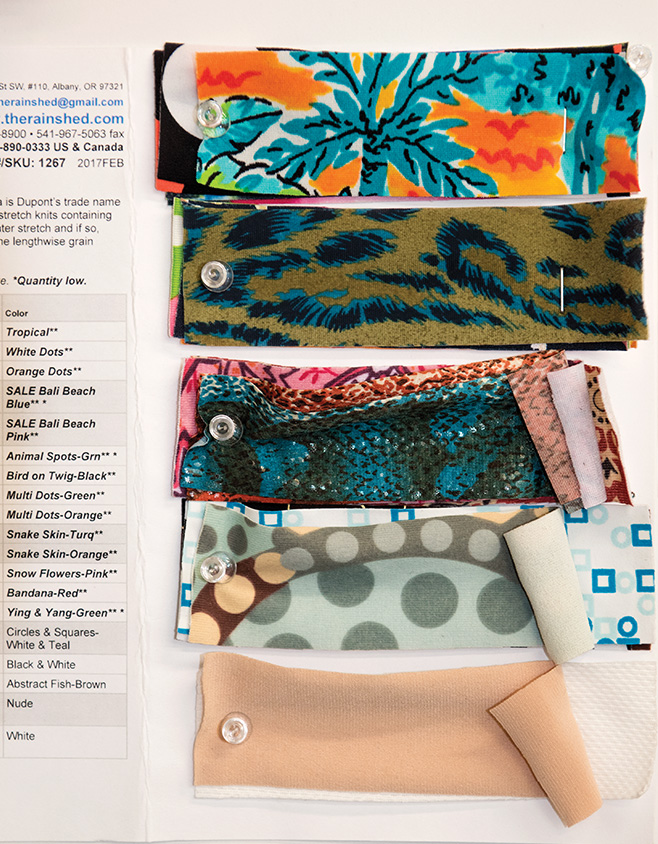

Rebecca Scheer was a student in Medlin’s first class in the fall of 2017. She and her teammates were tasked with designing an all-weather layering system for people with limited mobility. They often worked past midnight, perfecting their prototypes. The reward came when their

designs were chosen to appear on the runway during New York Fashion Week. “We call Angela our design mom,” says Scheer, 22, who’s now working as an apparel design intern in the San Francisco Bay area. “She expected the best from us because she saw the best in us.”

“Straight Outta Hamlet”

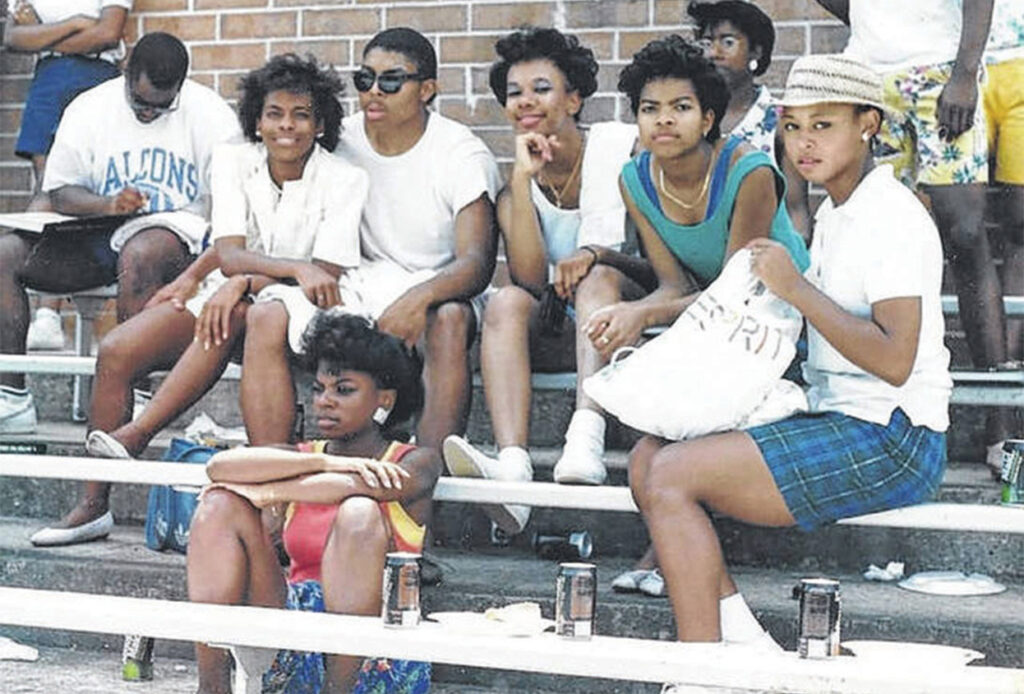

That’s the headline that tops a “hometown girl does good” article in the Richmond County (N.C.) Daily Journal from May 2018. The article includes a photo of Medlin with a group of high school friends in the mid ’80s, hanging out on the bleachers on a sunny day. She’s sporting preppy plaid Bermuda shorts and a crisp white polo shirt; a straw fedora and Esprit shopping bag give the impression that’s she’s got places to be, even then.

And she did. Medlin excelled in high school and graduated near the top of her class. Armed with a scholarship to attend any North Carolina university, she chose NC State for its design school. At the time, the school didn’t have a formal fashion track, so she created her own independent study program, focusing on fashion and textiles. Chandra Cox, Alumni Distinguished Professor of Art + Design, became her mentor and adviser. Cox recalls that Medlin had a “nice stylized drawing sense,” but what stood out was her hard work and determination: “Angela was just hungry.”

After graduating with a degree in environmental design, Medlin had an assortment of odd jobs before being hired as a design assistant at Cross Colours, the Los Angeles hip-hop brand known for its baggy jeans and positive message tees. At Cross Colours, Medlin got a crash course in casual fashion while rubbing elbows with sitcom stars and rap royalty. (She met rapper Tupac Shakur when she wandered into a tattoo parlor while waiting for a doctor’s appointment. She left with an African ankh inked on her left shoulder.) When Cross Colours folded a short time later, Medlin was scooped up by Adidas. From there, she landed high-profile gigs at Levi Strauss, Adidas (again) and The North Face.

During this period from the early ’90s to 2000s, the lines between athletic wear and street style were becoming increasingly blurred. Inspired by the hip-hop craze for track suits, flashy logos and status sneakers, companies such as Adidas and Nike partnered with famous athletes, entertainers and high-end fashion houses. At the same time, “Casual Friday” was rewriting corporate dress codes, and consumers were demanding greater comfort in their everyday wardrobes.

That marriage of function and fashion has always been a sweet spot for Medlin, who wears workout gear under her clothes so she can easily transition from the studio to the gym. At Adidas, she helped introduce sustainable, natural fabrics such as lightweight wool and linen to seasonal active wear. At The North Face, she was part of a design team that turned puffy coats into a fashion phenomenon, in the process building the company’s lifestyle outerwear category into a $3 million business. Cox recalls visiting New York and San Francisco during this time and seeing her former student’s designs everywhere. “Her gear was all the rage in urban America,” Cox says.

Today, those trends show no signs of cooling as athletic wear continues to influence fashion tastes from suburban shopping malls to European luxury labels. However, while Medlin pays close attention to what’s on the runways, she’s more interested in what people wear and what works for them in their everyday lives. Function comes first, she tells her students. “You can say you want to design the next Comme des Garçons inspired piece,” she says, referring to the avant-garde Japanese fashion label. “I’m going to ask, ‘How are you going to make this functional?’”

Paying It Forward

While function is the driving force in Medlin’s design philosophy, she encourages young designers to stay flexible and follow their passions. Onstage at the Portland Creative Conference, she recalls a time early in her career when she felt pressured to downplay her many creative interests — such as painting, illustrating and writing — for fear that she wouldn’t be taken seriously as an apparel designer. “You were put on a track,” she says, “and that’s where you lived.”

That started to change when she was living in the Bay Area, working for The North Face. She got involved with a community of free-thinking entrepreneurs, artists and musicians. She started painting again, something she hadn’t done since college. She organized an art show for fellow North Face employees. And she self-published a book of her own artwork and writing. Like that “little girl in the shack,” Medlin says, she was living her life without creative limits. “I was challenging myself not to be in anybody’s boxes.”

In 2014, Nike offered her a once-in-a-lifetime chance to revitalize the iconic Jordan apparel brand. For the next two years, she built a collection that paid homage to the original 1985 “Flight Suit” series but with a more modern streamlined fit, updated colors and high-performance fabrics. By 2016, however, she was ready to step out on her own. “It was at that moment I realized there was something bigger,” she says, “a next chapter that I was supposed to be doing.”

That “something bigger” turned out be the studio at Pensole, though it took a while for her to figure it out. After leaving Nike, Medlin worked on a variety of personal projects, including a line of high-end pet products inspired by her beloved bulldog, Wubbi. She launched a blog, shining a spotlight on designers of color. Now, as a mentor and teacher, she is starting to see how all of the pieces fit together.

On a December night, people and music spill out of the Pensole building into the cold night air. Up a flight of stairs, a wide hallway is packed with students, faculty, sponsors and guests celebrating the end of the 12-week session. With their final presentations complete, the students are eager to show off their work and talk about future plans. Their designs run the gamut from realistic to far-fetched. The team for the ultra-exclusive Amex “Black Card” label displays a futuristic sneaker in a matte black metal case.

Danish student Simone Bakke and her teammates chat with two representatives from Xenith, a Detroit company that makes football helmets and is hoping to expand into new markets. Michael Ryan, Xenith’s business development manager, admires Bakke’s design for a female soccer helmet, which in its final incarnation actually does resemble a crown with a crosshatch pattern that references the Xenith logo. “They really hit it out of the park,” Ryan says.

Boogying down the hallway in billowing white linen, Medlin is enjoying the moment. She describes the scene earlier in the day when students were nervously practicing their pitches, like actors rehearsing their lines. She is reminded of how her career began: that first star-struck interview at Cross Colours, where she nearly tripped over the teen hip-hop duo Kris Kross on her way in the door. She was amazed when the design director offered her a job on the spot, then left her alone with the use of his private phone. “I was on the line for an hour calling everybody I knew,” she says.

For a girl from Hamlet, that was big news. Now she’s opening those doors for the next generation.