The Right Stuff

Christina Hammock Koch ’01, ’02 MS is ready for her next frontier—OUTER SPACE.

HOUSTON, Texas—Along with students across the country, Christina Hammock Koch ’01, ’02 MS and her first-grade classmates at St. Francis of Assisi School in Jacksonville, N.C., were watching on television when the Space Shuttle Challenger blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on the morning of Jan. 28, 1986. They were taking a break from their studies to watch because Christa McAuliffe, selected to be the first teacher in space, was on board. But 73 seconds into liftoff, its smoky plume still marking its departure from Earth, Challenger exploded. All seven crew members were killed.

Like her classmates, Koch was shocked by what she had seen. For many of the students watching that day, it was their first exposure to the space program. Neil Armstrong’s first step on the moon happened long before they were born, and they were too young to remember Sally Ride becoming the first American woman in space in 1983.

Koch, one day before her seventh birthday, felt the sorrow that comes with such a tragedy. But even at her age, she had a sense of the promise that manned space flight offered. “Seeing that our country was mourning something that was kind of big enough and important enough to do, but that was also dangerous and challenging, I think that probably caught my attention, even at that young age,” Koch says. “If anything, it was, ‘Let’s get back to space.’”

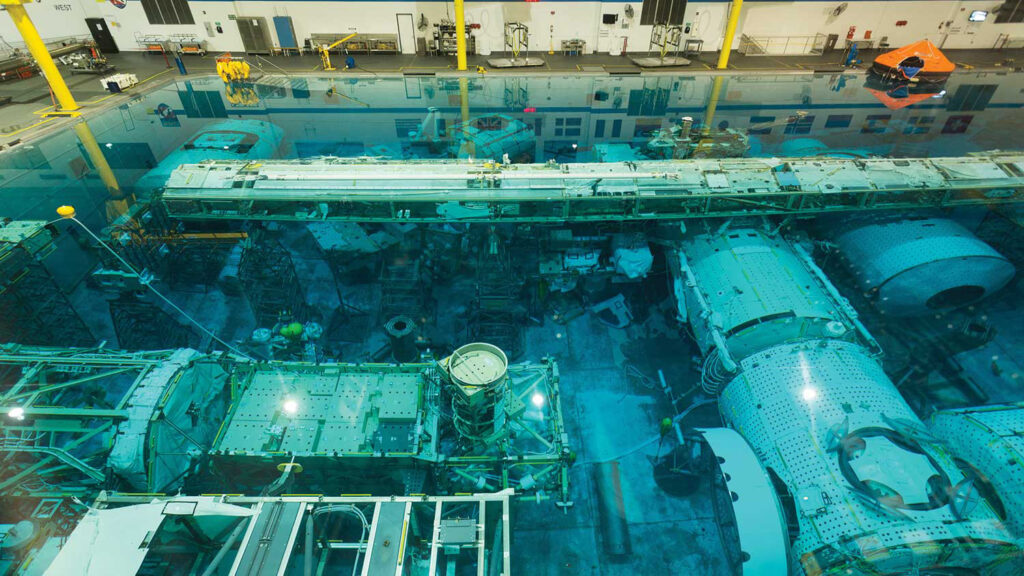

Some 30 years later, Koch is ready. She is one of NASA’s newest astronauts, one of eight men and women chosen from more than 6,000 applicants in 2013 to make up the 21st class of astronauts. They have spent the past two years in training, mostly at the Johnson Space Center on the outskirts of Houston. They have survived in the wilderness, learned how to speak Russian, experienced zero gravity and figured out how to work while wearing a bulky spacesuit. They have flown supersonic jets, spent hours at a time working underwater on a massive mockup of the International Space Station and learned how to control the space station’s robotic arm.

With their initial training completed, the four men and four women are now full-fledged astronauts. They are waiting to get their first mission into space, a process that can take years, and the more focused training that will precede that mission. For Koch, the most likely scenario is an extended stay on the International Space Station, a prospect that she faces with the same sort of excitement that she felt as a kid who built model space shuttles for school science fairs and cut pictures of space out of magazines to tape on her bedroom walls. “The space station,” she says, “would be one of my dream assignments.”

“The space station would be one of my dream assignments.”

— Christina Hammock Koch ’01, ’02 MS

It is a dream that has been years in the making.

Koch says she always wanted to be an astronaut, a role that would enable her to explore new frontiers. She grew up in a household where intellectual exploration was the norm. Her father was a physician and “arm-chair astronomer,” while her mother was a middle school math teacher. There were plenty of magazines about space and science around the house, and dinner-time conversations with her parents and three younger siblings (all of whom would also go to NC State) were more likely to be about black holes than the ups and downs of the local sports teams. She would cut photos of Antarctica and other exotic locations out of National Geographic and put them on the walls along-side her space pictures. “All of these places that were on the frontiers, places to be explored, just caught my interest from the time I was really young,” Koch says.

A Stellar Student

With that dream in mind, Koch took on a challenging double major of electrical engineering and physics as a student at NC State. “I didn’t want to just make things and not understand the theory behind it,” she says. “And I didn’t want to just have theory without being able to use my hands and create things.” She had a perfect 4.0 GPA in both of her undergraduate majors (although she admits to getting a “B” in a graduate course). But her interests extended well beyond the classroom. Koch participated in a head-spinning list of extracurricular activities—from providing housing maintenance in Hispanic communities with Engineers Without Borders to taking photographs for the Technician and volunteering with Habitat for Humanity—all while working part-time at places like Kmart and Blockbuster Video. She traveled to Ghana in 1999 to spend a semester studying abroad, only to find out when she got there that the university was no longer offering many of the courses she planned to take. She decided to spend her newfound free time tutoring local students.

“I consider myself very driven, but not competitive, and I think there’s a little bit of a difference. I consider myself more cooperative.”

— Christina Hammock Koch ’01, ’02 MS

“Most people would have come on home,” says Cecilia Townsend, the coordinator of undergraduate programs in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and one of Koch’s advisers when she was an undergraduate student. “But she stayed and tutored other kids. I’ve just never seen anyone who goes for it with such intensity.”

Koch says she has always looked for ways to challenge herself, be it by taking up rock climbing or deciding to build her own Tesla coil, a transformer that produces electricity. “I consider myself very driven, but not competitive, and I think there’s a little bit of a difference,” she says. “I consider myself more cooperative. I really like to make sure that as many people who are around me, that we’re all doing well.”

“I definitely like the idea of exploring, going somewhere new, and places where there are physical challenges along with the intellectual challenges.”

— Christina Hammock Koch ’01, ’02 MS

After finishing her studies at NC State, Koch understood that her dream of becoming an astronaut was a long shot and that it didn’t make sense to concentrate on building a résumé that might someday impress NASA officials. Instead, she pursued jobs that would challenge her while also allowing her to explore the world. If it ended up leading to a job as an astronaut, that would be the icing on the cake. “I definitely like the idea of exploring, going somewhere new, and places where there are physical challenges along with the intellectual challenges,” she says.

Exploring the World

That approach led her to jobs related to space exploration, such as a stint as an electrical engineer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s Laboratory for High Energy Astrophysics in Greenbelt, Md. But it also led her to unrelated work in remote locations such as Antarctica and Greenland, where she ran the instruments for research being conducted there by various organizations. She once worked in minus 105 degrees at the South Pole (“If you have the right clothing, it’s actually doable,” she says) and has a photo of ice encrusting her eyelashes while she was working at a lab in Greenland.

Then, in 2011, NASA put out the word that it was accepting applications for the next class of astronauts, and Koch submitted her application. It took NASA months to cull the initial 6,000-plus applicants to 120, who were brought in for initial interviews and medical exams. Koch made the final cut to a list of 50, who had more interviews. NASA was not simply trying to find the best eight candidates, but a class that included people with a cross-section of experiences—as pilots, physicians, scientists or engineers.

“When you get to that last interview, that last 50, we’re looking for people that we think will get along well with each other, that just have the personality and experiences that makes you want to work with them on a daily basis,” says Pat Forrester, a veteran astronaut who supervised the training of Koch’s class.

Koch was working as station chief for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s climate observatory in American Samoa when she got the call. “The person on the other end of the line had to ask me if I was still there, because I was just silent,” Koch says. “I just thought, ‘That’s weird. She just said she wanted me to come to Houston and be an astronaut. But there’s no way that’s what she said.’ ”

Koch joined three women and four men at the sprawling Johnson Space Center campus that summer. They all found homes in the Houston area—Koch lives along the Gulf of Mexico in Galveston, Texas—and arrive to work each day just like the thousands of engineers and other civil servants who work there. Unless they are preparing to fly or training in a spacesuit, the astronauts blend in with everyone else. (Koch carries with her a tattered backpack that she has had since her days at NC State.)

As astronaut candidates, they still had two years of training ahead of them before they could call themselves full-fledged astronauts. But they would be a different sort of astronaut, working for a space agency that doesn’t enjoy the high profile that it once did.

A New Kind of Astronaut

The exploration of space by the United States has been on hold since the space shuttle’s mission in 2011. Many Americans are unaware that astronauts are still at work (typically for six-month stints) on the International Space Station, which has been occupied since November 2000, or that Americans use the Russian space vehicle Soyuz to get there. And while astronauts were once primarily military pilots, men like John Glenn and Alan Shephard who were comfortable flying at high speeds, Koch had never flown a plane and had no military background. Today’s astronaut needs to be more versatile. Pilots are still needed, but astronauts also have to be able to take care of themselves—and their equipment—during long stays in the International Space Station. “The designation between pilot and non-pilot are still present, but other than that we’re really required to have all the skills,” Koch says. “We have to be plug-and-play.”

It was a challenging training regimen. “If they can turn me into a pilot—well, not a pilot—but if they can turn me into someone who’s comfortable in a supersonic jet, then they know what they’re doing,” Koch says of the flight school in Pensacola, Fla., that she went through. The engineering that went into the jets fascinated her. “She really likes a lot of the instrument navigation systems we use,” says Jessica Meir, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School before she was selected as one of the candidates in Koch’s class. “She likes getting down to the nitty gritty, learning tricks that some of the pilots don’t even know.”

Then there were the unexpected lessons, like learning not to wear jewelry while wearing their flight suits. That bit of information was passed on to Koch and Meir by the other two women in the class, both of whom are experienced pilots. “We went from being really successful to being the lowest rung on the totem pole,” says Meir. “You have to have a lot of patience.”

Koch was in her element during the wilderness training, leading hikes up difficult terrain as part of the National Outdoor Leadership School in Wyoming and helping others set up camp and start fires. “She knows what it’s like to live with other people in stressful situations,” says Lt. Col. Drew Morgan, an Army doctor who is a member of the new astronaut class.

One of the most difficult challenges was getting used to the spacesuit, which is bulky and cumbersome and, surprisingly, not custom-made for each astronaut. In fact, the suits used today were made when most of the astronauts were males, so they are too large for the female astronauts. Koch and other female astronauts stuffed padding into the suit so they would not bounce around inside of it. They would then replicate space walks in zero gravity by spending six hours working underwater on the exterior of a mock-up of the space station in a massive pool. Divers move them from spot to spot, but the astronauts had to learn to use tools with their arms encased in tubes and large gloves. Koch says it’s like squeezing a tennis ball for six consecutive hours. And then there are the unexpected difficulties—like the inability to scratch an itch on your nose.

“It’s just physically hard to move,” says Koch. “Every little motion you do is difficult.”

Coolest Job in the World

That doesn’t mean that Koch and her classmates didn’t enjoy their training. “Going to space is the coolest job in the world,” says Morgan. “Training to go to space is the second coolest thing in the world.”

Koch agrees, and that excitement is evident one day when she and Meir are walking through what is known simply as Building 9. It is, in essence, a large hangar full of life-size space toys—from a mock-up of part of the space station to a robotic astronaut known simply as Robonaut. As a tour group looks on from a walkway above, Koch and Meir are thrilled to be getting their first chance to sit inside a mock-up of a space capsule known as Orion, even if it is only to get some photos. The actual capsule is under development elsewhere, with plans that it will one day be the next NASA vehicle to take astronauts beyond Earth’s orbit and possibly on to Mars.

“We’ve been waiting for this our whole lives,” Meir says.

“No question about that,” says Koch. “Some things do just turn into your normal work day—getting into a spacesuit, blah, blah, blah. In some ways, you do get used to it. But in other ways, you have moments when you realize how amazing it is. Day to day, we’re still excited.”

The eight astronaut candidates leaned on each other to get through the two years of initial training. They learned that they could count on Koch (who is known to her fellow astronauts by her call sign of “Nana,” a reflection of her caring nature) to look after them—by remembering a birthday, letting loose a timely one-liner during a tense situation or simply offering a helping hand to someone facing a difficult challenge. “She is very aware of how somebody may be feeling at any given time,” Morgan says.

It’s that approach that may ultimately be one of Koch’s greatest assets as she awaits her first space mission, which could take years. In the meantime, Koch’s responsibilities include providing ground support to the ongoing missions in the space station, giving the engineers at NASA input on items being developed to be used in the station.

Forrester, the astronaut who supervised the training of the most recent astronaut class, says Koch’s experience working with research equipment in severe conditions such as the South Pole and Greenland, as well as her engineering background, make her well-suited for the roles that astronauts must fill on the space station. But he says her approach—from her encouragement of others to her never-say-die attitude—may be equally important. “We need somebody who can go up there and live well and work well and get along and enjoy it,’’ he says. “She’s the perfect kind of person to do that.”

Koch is ready, and has been for a long time. As a student at NC State, Koch wrote in a scholarship application that the future of the space program could not be brighter and that she was fascinated by the frontiers of space exploration.

“It is the stars I’m after,” she wrote.