On the Beach

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day, we’ve pulled this Summer 2016 story from our archives. It tells the stories of the NC State boys buried at the Normandy American Cemetery and some who were among those who gave their lives in the struggle for victory that began on Normandy’s shores.

SAINT LAURENT-SUR-MER, France — The sand of Normandy’s coast is cold on Omaha Beach on a late October day, but families take advantage of a sunny, cloudless afternoon. A father is holding a baby wearing only a diaper over the waves, and the child laughs as a wave tickles its feet. Nearby, another father tells his three children to stop building sandcastles. Their beach day is at its end.

Forty yards away from the vacationers, two collections of 20-feet-high swords jut out of the sand and pierce the air. They bookend two steel posts in front of more jagged structures. This is Les Braves, the monument on the shore paying tribute to the Allied troops who landed here — and on other Normandy beaches, including Utah, Gold, Juno and Sword — on June 6, 1944.

It was on that morning that Operation Overlord and a new path to an Allied victory in Europe unfolded. More than 160,000 Allied troops hit these shores as the invasion began, and by day’s end, 10,000 of those men were dead, wounded or missing. Les Braves, along with other memorials and museums on the 50-mile shoreline of Normandy, promises that the world will never forget the men who overcame the choppy water, chilled misery, seasickness and the spray of German machine guns to make the invasion of Normandy the essential moment of World War II and perhaps the 20th century.

“It’s decisive for the last 100 years of history,’’ says Dan Bolger, a retired U.S. Army lieutenant general who teaches military history at NC State. “It’s decisive that America is a superpower. If someone said, ‘Name the location where that happened,’ Normandy is it.”

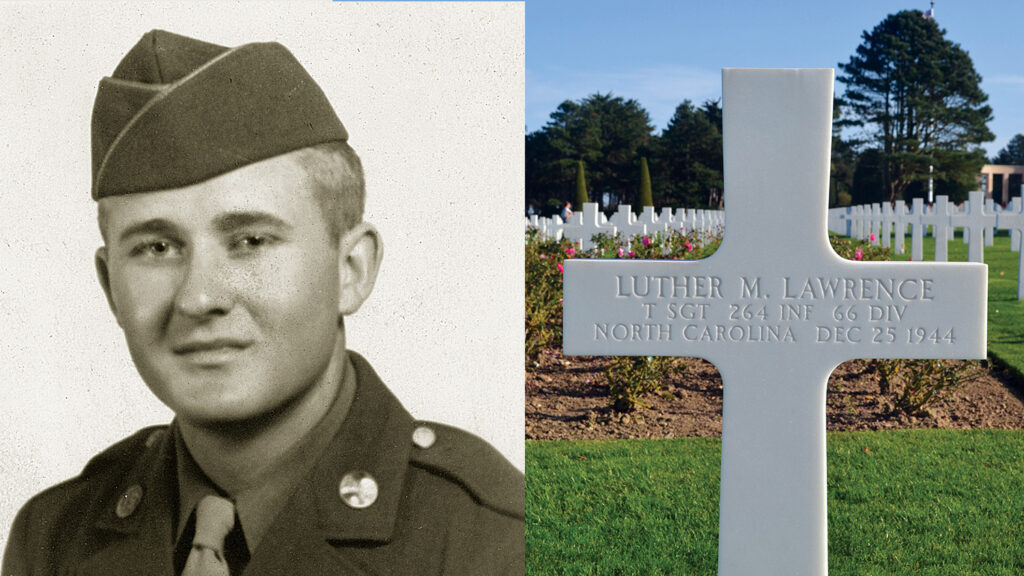

Three miles up the coastline is the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, where 9,387 marble crosses and Stars of David as white as new bars of soap are lined up on a green lawn overlooking the English Channel. Six NC State alumni are buried here, and scores of others were among the young men who fought and died as the war unfolded on these shores. Many played pivotal roles in preparing for and taking part in the invasion on those days in early June of 1944; some came to Normandy in the weeks and months following D-Day, making their way inland to France as the Allies surged through Europe.

The stories of these soldiers — from one of the most famous names in NC State’s history to a star engineering student to a tobacco researcher — have been stored away in dusty file cabinets in the basement of the Park Alumni Center. Some of the files hold only a brief obituary; others are filled with news clippings, wedding announcements, military records and photographs. There are letters sent to the Alumni Association, some penned by family members who wanted to make sure that their son’s alma mater knew of their lives and fates. Others are from the soldiers who were at the center of the war’s storm, but who still felt the need to reach out to the place where they had studied and planned their futures — futures that would never be realized. What follows are some of their stories.

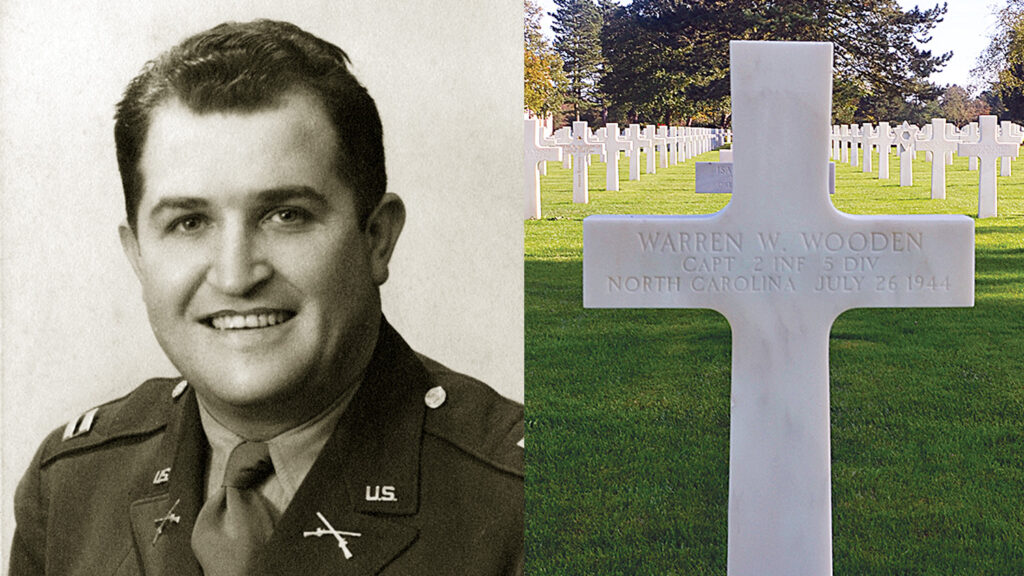

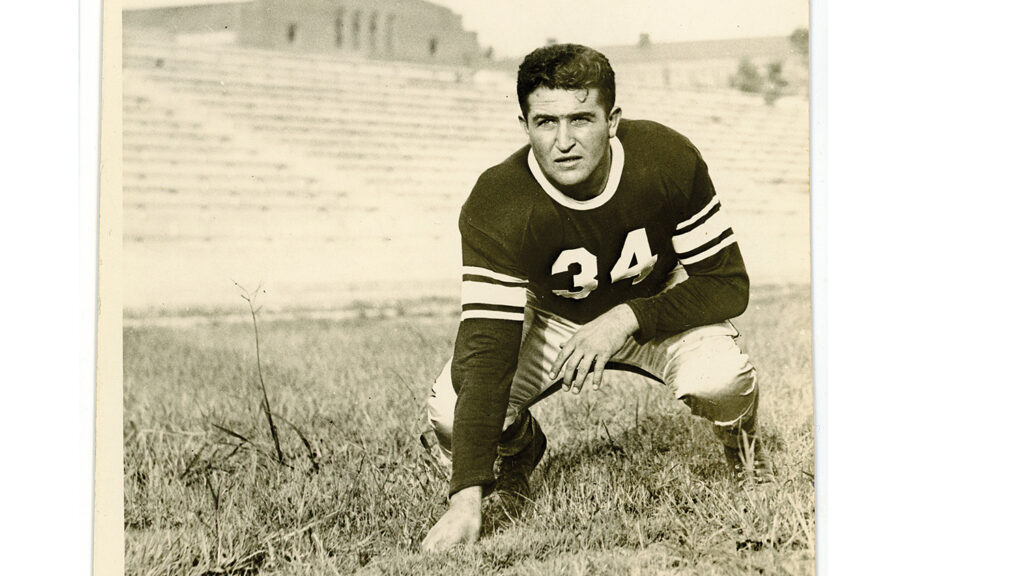

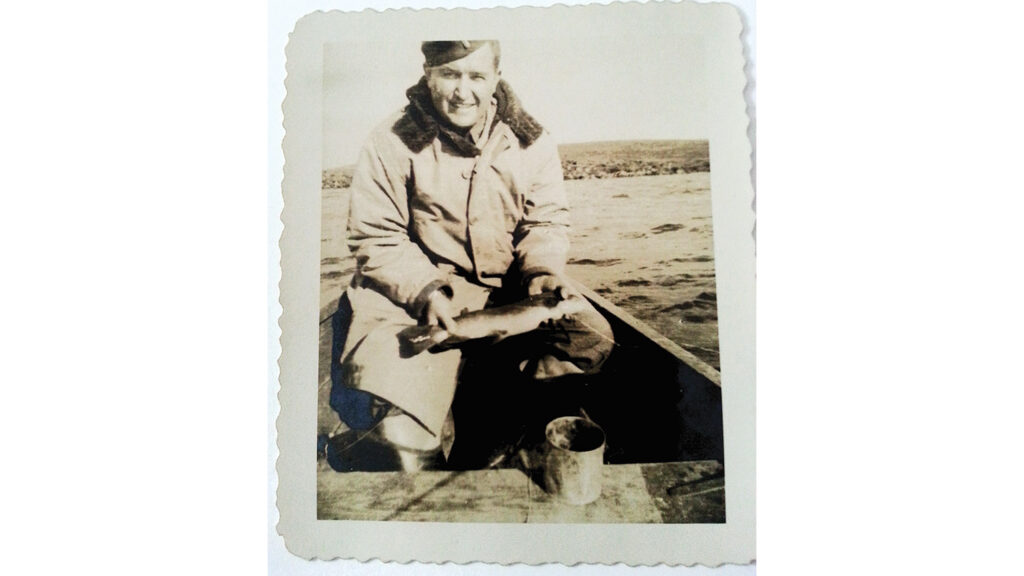

Capt. Warren Wooden ’38

U.S. Army, 2nd Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, Baltimore, Md. | 1914 – 1944

During the mid-1930s, Warren Wooden ’38 carved out a memorable career as a rugged member of the Wolfpack’s football squad. Originally from Baltimore, Md., he played guard on the offensive line, even being named “This Week’s Wolf” one season. “Warren gets the place of honor this week for his fine play throughout last season and his steady show of improvement this year,” reads a news clipping.

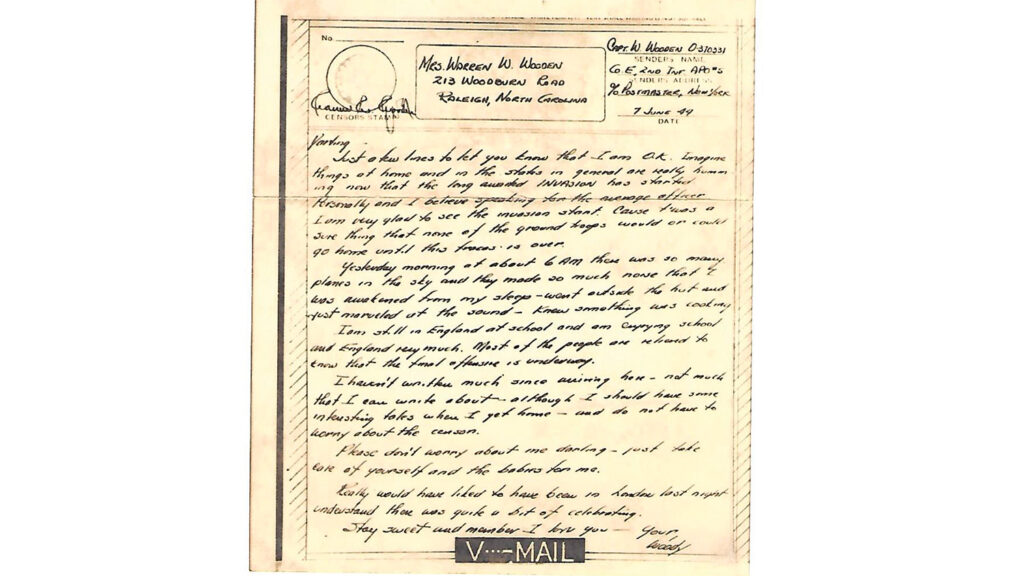

After college, Wooden married Betsy Jane Senter of Raleigh, who wore to the ceremony a rose tweed suit with a corsage made of an orchid and lilies of the valley. The couple, after a honeymoon to Florida, moved to Bassett, Va. Wooden, who held a forestry degree, worked at Fairy Stone State Park and loved to play pinochle and poker for money. The couple had a son, and a daughter was born after Wooden left for England in 1942. In a letter to his wife dated June 7, 1944, Wooden offered an account from his station in England, across the English Channel from Normandy, of the invasion’s opening chapter: “Yesterday morning at about 6 a.m. there was [sic] so many planes in the sky and they made so much noise that I was awakened from my sleep — went outside the hut and just marveled at the sound — knew something was cooking.”

“Yesterday morning at about 6 a.m. there was [sic] so many planes in the sky and they made so much noise that I was awakened from my sleep — went outside the hut and just marveled at the sound — knew something was cooking.”

— Capt. Warren Wooden ’38

Wooden acknowledged in the letter, which his daughter still holds onto, that he had not written in a long time, saying, “. . . not much that I can write about.” He promised some interesting stories from the war, but said he was worried about putting them in his letters for fear of the censors. He begged her not to worry about him and to take care of their children. He ended it with two simple orders: “Stay sweet and member I love you. Your Woody.”

A month later, the Army captain landed on Utah Beach on July 9 as part of the effort to take Saint-Lo in Lower Normandy. He was killed 17 days later in the hedgerows, memorialized in the Normandy American Cemetery with a marble cross bearing his name.

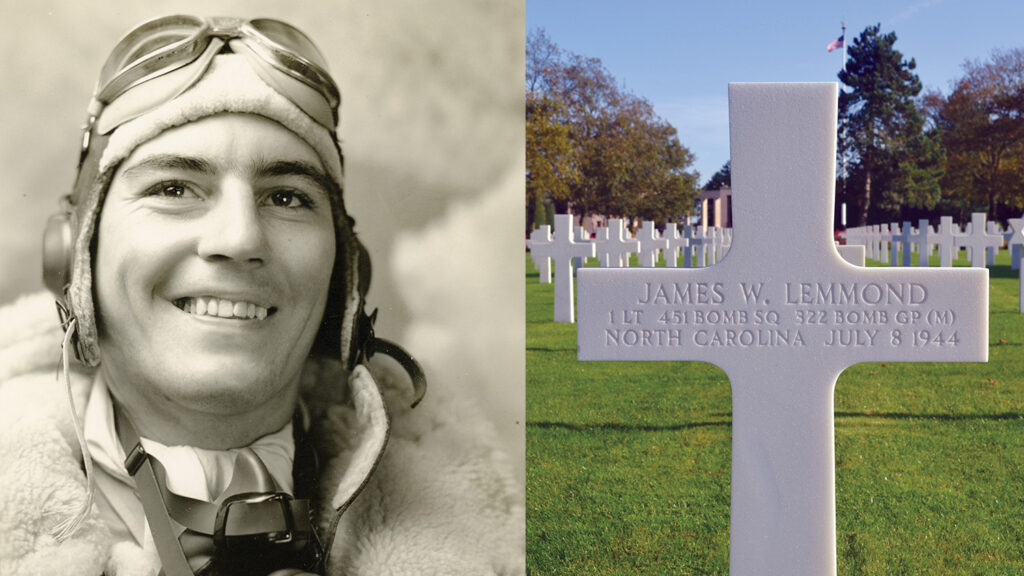

1st Lt. James Lemmond ’43

U.S. Army Air Forces, 451st Bomber Squadron, 322nd Bomber Group, Monroe, N.C. | 1921 – 1944

James “Buck” Lemmond ’43 grew up one of nine children in Monroe, N.C. In high school, he was an exceptional athlete who starred in football, baseball and boxing (TKO’d only once), and was president of the National Honor Society. He came to NC State to study mechanical engineering, joining the National Guard and transferring to the Air Corps. There’s a Lemmond family legend alive today about a time Buck buzzed over his hometown to say hello on a flight to Washington, D.C. “I was just a little kid the last time I saw him,” says his brother Vaughn Lemmond, 89, who lives in Monroe. “I was sick. My mother let me get up to see the plane.”

A short time before he was deployed to England, he married Carrie Broom. When Lemmond took his flying prowess to Europe, he targeted railroad houses and yards, trains and bomb platforms on more than 55 missions in his B-26 Marauder, which he called the “Carrie B.” And to further remember his wife, he carried a little plastic baby shoe on each mission, which he credited for his luck and survival. The shoe also served as a promise that he would make it back stateside to start a family with his wife, a promise Lemmond couldn’t fulfill. His last mission was a night bombing that targeted a bomb platform between Abbeville and Doullens in France. His plane never made it back, and he went missing over France July 8, 1944. Lemmond was declared dead the next year. In a note typed to the Alumni Association in 1945, his father explained: “The War Dept have [sic] notified me that according to the Laws and regurlations [sic] they would have to delcair [sic] him killed in action after the expiration of one year and A Day.”

Maj. Alexander Newton ’33

U.S. Army, 4th Armored Division, Knoxville, Tenn. | 1910 – 1944

Alexander Newton ’33 loved world travel, and his time as an engineer in petroleum exploration and as a major in the Army’s infantry armored corps took him across the globe, including through the Middle East. Newton’s writing is filled with vivid descriptions of the sights in Iraq, Syria and Palestine. And he wrote of how important it was to hear news from Raleigh. “About all I ever hear is the news that comes in the Alumni News, and that is several months late, but quite a bit better than none at all,” he wrote in a 1940 letter to C.L. Mann ’99, a professor of civil engineering at NC State. “The entire football season will probably be over before I hear the results of the first game.”

Newton also wrote of his time prospecting for oil in the Hammar marshes along the lower Euphrates River. “You get to see a lot of very very old country, and the Garden of Eden is supposed to be located in the middle of the country I am working,” he wrote. It was that love of foreign sites his mother lamented in a 1945 letter to H.W. Taylor ’26, ’27 MS, director of alumni affairs, informing NC State of her son’s death. He had been killed in action either in Normandy or Brittany, France, according to his military record. “He used to say, ‘so much beauty in the world mother’— shame he won’t see it,” she wrote. “I hope where he has gone is so beautiful he will not mind what he missed here.” Newton was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

“He used to say, ‘so much beauty in the world mother’—shame he won’t see it. I hope where he has gone is so beautiful he will not mind what he missed here.”

— Mother of Maj. Alexander Newton ’33

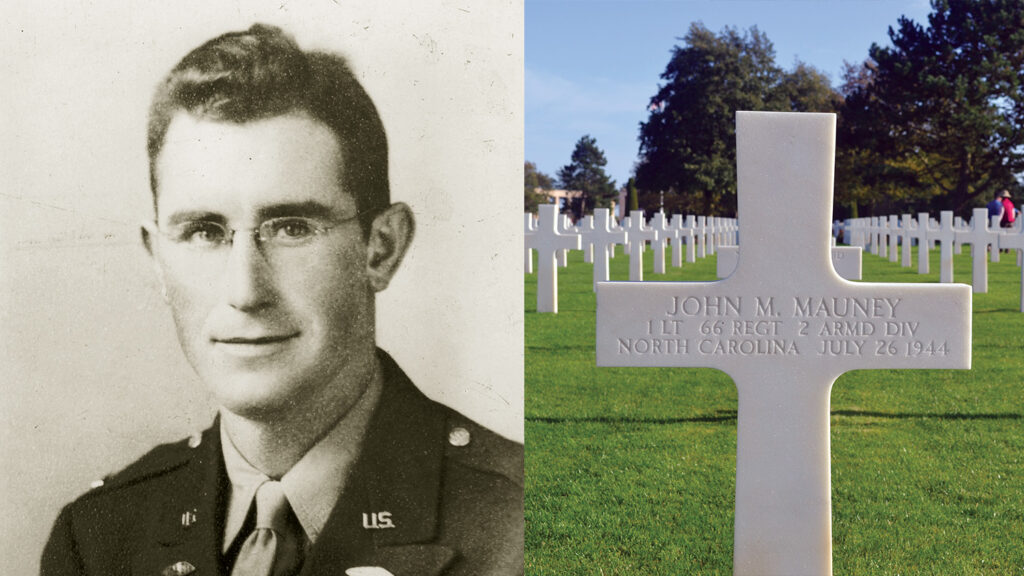

1st Lt. John Mauney ’40

U.S. Army, 66th Regiment, 2nd Armored Division, Lincolnton, N.C. | 1919 – 1944

In his senior picture in the Agromeck, John Mauney ’40 looks professorial, wearing glasses and looking straight ahead. Mauney came to France in 1944 soon after the first day of the invasion as a highly decorated 1st lieutenant in the 2nd Armored Division. Mauney had taken on tanks in a North African battle near Mehdia, Morocco, according to a war department account cited in a news clipping. “His tank attacked two of the enemy tanks and drove them both away,” the account read. “His own tank was thrice hit and the periscope put out of commission, so Mauney mounted the turret, and exposed to the fire of the enemy’s small arms, directed the action.”

Once in France, Mauney, a 25-year-old from Lincolnton, N.C., prepared for what he described in a July 7, 1944, letter to the Alumni Association as “the big push.” He wrote of running into other NC State boys while stationed in England and some of whom were with him. “Lt. Jack Getsinger ’40, is in the 66th A.R. with me and so is Lt. E.V. Helms (’38 or ’39),” he wrote. “Jack was wounded in the heel in the invasion of Sicily, and spent several months in a North African hospital, but he’s back with us now. E.V. is sporting a purple heart, too, from Sicily and a Soldiers Medal from Africa.”

Mauney’s sense of humor is apparent in the letter, relating the story of how he was once mistaken for a German officer by an American enlisted man — and thankful to survive the doughboy’s fire. The Army lieutenant longed to be back at NC State, where he had sung in University Choir and played in the Red Coat Band, promising to send his annual dues when he could. “I would send the $3.00 from France, but I don’t believe you’d care for the francs. We had our first pay day today,” he wrote. “Surely wish I could have been back at State for Alumni Day, but you see how things are. Perhaps we’ll get to be there next year . . . I’m pretty optimistic right now.”

Mauney was killed 19 days later and is buried in Plot E, Row 21, Grave 22 in the Normandy American Cemetery.

1st Lt. Joseph O’Brian ’40

U.S. Army, 401st Glider Infantry Regiment, Oxford, N.C. | 1914 – 1944

Joseph O’Brian ’40 was living in Oxford, N.C., and working at the Experiment Tobacco Station when he entered the Army in February 1942. Two years later, he was a 1st lieutenant in the 401st Glider Infantry and an executive and intelligence officer for a unit that was, according to a September 1944 obituary, noted for its “magnificent performance in the landing in an effort to safeguard the thrust from the sea in the invasion of Normandy on D-Day.”

O’Brian’s sister, Audrey, submitted his military records in late 1944 to NC State for record-keeping. Included in those materials is a list of posthumous honors for his heroism when he died during the invasion’s second day, June 7, 1944. There’s also a copy of a letter from Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson awarding the Purple Heart to her brother along with a message from President Franklin D. Roosevelt that reads, “He stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live, and grow and increase its blessings. Freedom lives, and through it, he lives in a way that humbles the undertakings of most men.”

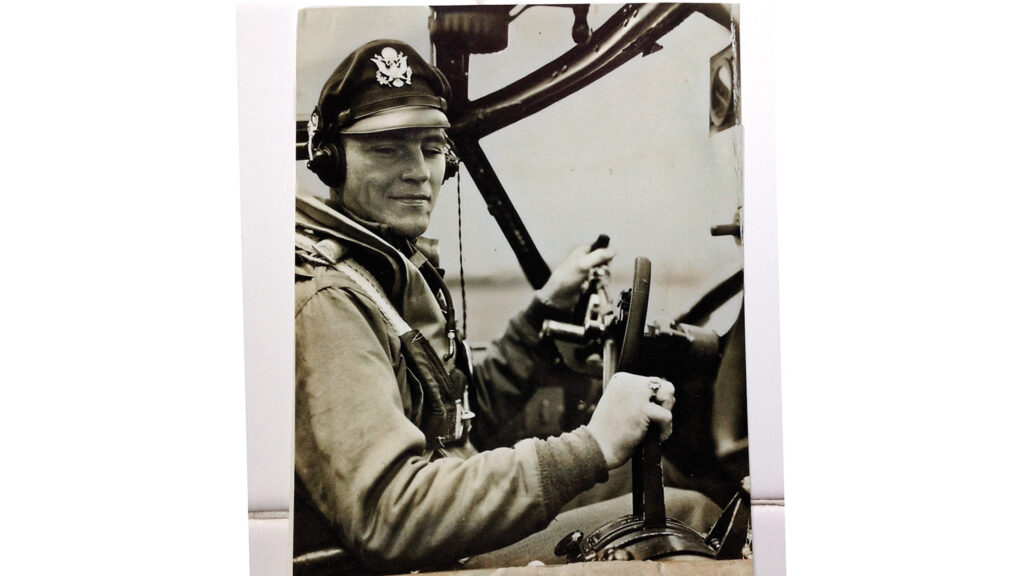

1st Lt. Victor Idol Jr. ’42

U.S. Army Air Forces, 366th Fighter Squadron, 358th Fighter Group, Madison, N.C. | 1920 – 1944

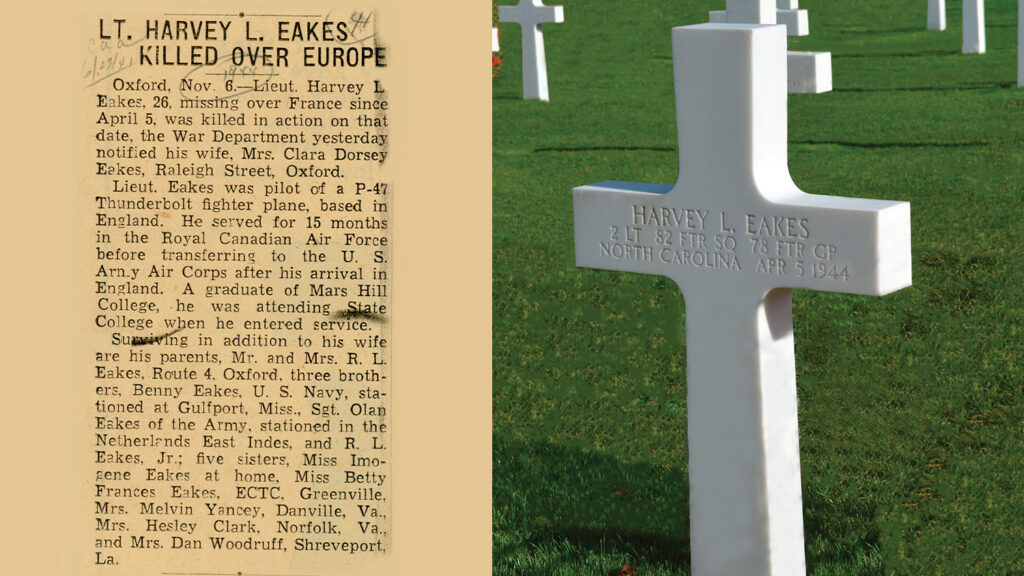

Victor Idol ’42 left Madison, N.C., after high school to attend Virginia Military Institute. But he transferred to NC State in 1938 and studied electrical engineering for two years before leaving college for health reasons. He enlisted in 1941 and trained as a U.S. Army Air Corps pilot in Randolph Field, Texas; Richmond, Va.; Orlando, Fla.; and Millville, N.J. In 1942, he left for England as a member of the 366th Fighter Squadron.

Idol came to fly more than 100 missions over enemy territory, most of which he piloted in the cockpit of his P-47 Thunderbolt. “When the P-47 plane, once used as a high altitude fighter and escort, became officially known as a Fighter-Bomber — it took part in strafing and dive bombing ground forces, gun emplacements and enemy supply lines,” a 1944 news clipping reported. “Lt. Idol took part in almost continuous allied bombing assaults as a prelude to the invasion of Europe, smashing the way for ground troops in Normandy.” Idol, who was awarded the Air Medal, went missing on a mission over the Cherbourg Peninsula 11 days after D-Day, and “was last seen parachuting from his plane over La Haye du Puits, France.” He was subsequently reported dead.

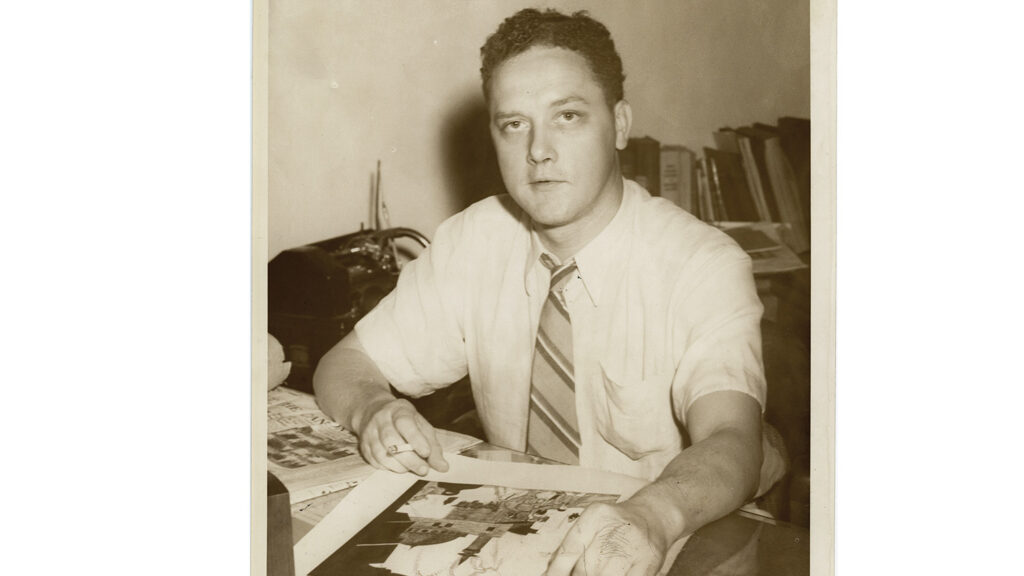

Lt. j.g. William Blue ’42

U.S. Navy Reserve, Carthage, N.C. | 1921 – 1944

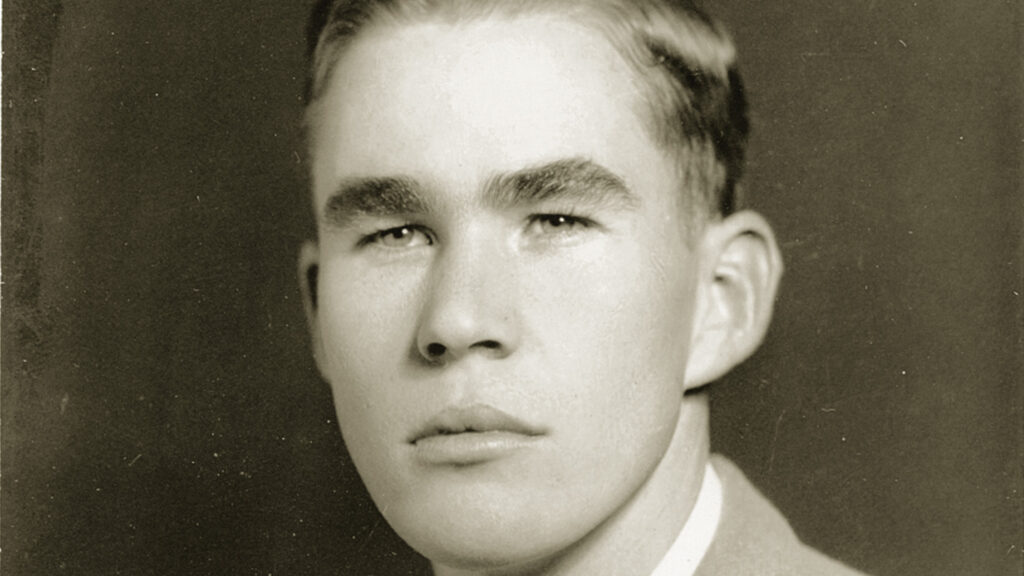

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini met near Austria in April 1942 to figure out why the Axis efforts in North Africa were going so poorly. That same month, William Blue ’42 received a gold watch.

The timepiece, handed out by the Student Engineers Council in NC State’s School of Engineering, went to the department’s top student. Blue, whose heavy eyebrows draped his smoky glance, was the choice that April. He had served as chairman of the student branch of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, garnered the respect of his peers and professors, and been celebrated for his oratory skills, delivering an address that January to the N.C. Society of Engineers. “For these reasons,” wrote Engineering Dean Blake Van Leer, “and also because you are an efficient engineer, an honorable gentleman and a loyal student of State College, it is my pleasure . . . to award you this gold wrist watch, suitably engraved as The Most Outstanding Student. . . . We are confident that you will wear this souvenir with pleasure to yourself and honor to your Alma Mater.”

The Carthage, N.C., native enlisted in the Navy, where he became a lieutenant and was on active duty two months after his graduation. He spent five months at the naval training school at Harvard University followed by the naval training school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He married Elizabeth Anne Maloney of Springfield, Mass., and they had a son. By February 1944, he had landed overseas and, that summer, was part of the U.S. forces’ movement southwest of out Normandy into Brittany. His job was to eliminate German radar dispersed along the French coast used in tracking English aircraft. As he was driving his Jeep on one of those missions, he hit a German mine and died in August.

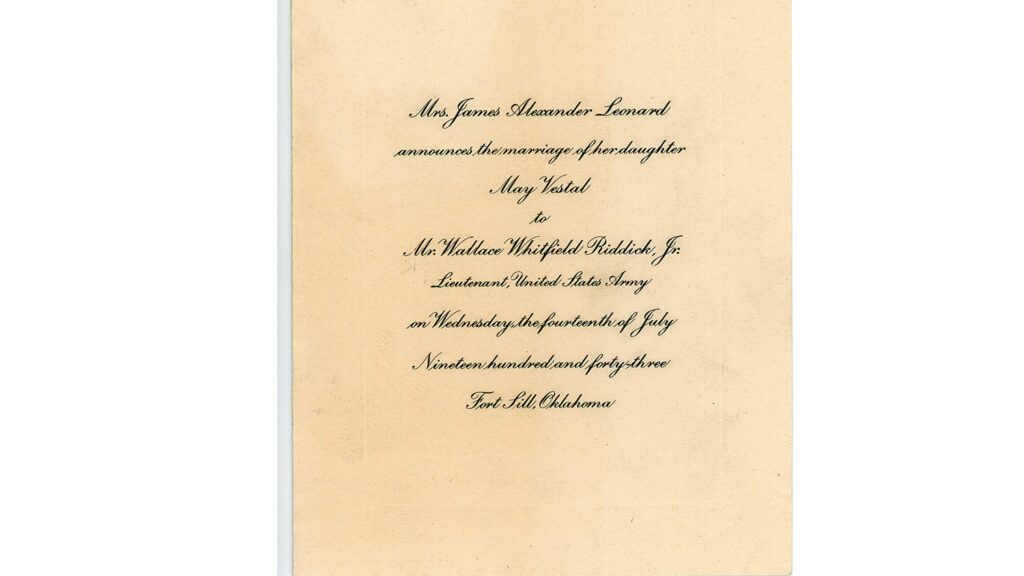

1st Lt. Wallace W. Riddick Jr. ’40

U.S. Army, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, Raleigh, N.C. | 1919 – 1944

Wallace W. Riddick Jr. ’40 was born in Raleigh, the grandson of W.C. Riddick, who served as president of North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering as well as football coach and the first dean of engineering. (Riddick Field and Riddick Hall were named in honor of the elder Riddick.) Riddick Jr. received his degree in textiles and later worked as an assistant superintendent at the Lexington Silk Mill in Lexington, N.C. He was a reserve officer in 1942 when he was called to active service on the heels of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. A year later, he married May Vestal Leonard in Fort Sill, Okla., in the same chapel where his parents had married during World War I.

Riddick Jr. arrived in France in June 1944 as a replacement officer with the 116th Infantry, which was making a surge toward Germany. He was wounded twice that summer before he was killed Sept. 1, 1944, at the Battle of Brest in northwestern France.

THIS EMBATTLED SHORE, PORTAL OF FREEDOM, IS FOREVER HALLOWED BY THE IDEALS, THE VALOR AND THE SACRIFICE OF OUR FELLOW COUNTRYMEN.

Pfc. Stanley Mulford Jr.

U.S. Army National Guard, 320th Infantry Regiment, 35th Infantry Division, Matthews, N.C. | 1924 – 1944

An infantryman who was rated “expert” with a Garland rifle, carbine and sub-machine gun, Stanley Mulford Jr. arrived at the front in France in late September 1944. During a fire fight at Bermering, he was hit by shrapnel and died Dec. 4, 1944, in Nancy. Mulford died before finishing at NC State.

There was a bit of irony attached to Mulford’s death, at least for his parents. According to a 1944 newspaper clipping, they had received a letter dated Nov. 29, 1944, in which he described his Thanksgiving.

“Dear Mother and Dad,’’ the letter read. “We had our Thanksgiving a week before Thanksgiving. We butchered a calf, a hog, about eight chickens, two ducks and two turkeys. Same old gumbo about the mud; it oozes up to your ears every time you turn around. I’m back in a safe place now so don’t worry about me. I’m safe and sound and will write again when I have something interesting to say. Love to all, Stanley.’’

The day after receiving that letter, the Mulfords received a telegram at their home in Matthews informing them their son was dead.

Editor’s Note: Chris Saunders, associate editor of NC State magazine, was host of a 2014 NC State Alumni Association trip to France, where travelers walked the beaches and explored the monuments of Normandy.

- Categories: