Pencil Sketches Full of Promise

A plane crash took the life of a Design professor who had grand visions for the N.C. State Fair. This story was originally published fall of 2014.

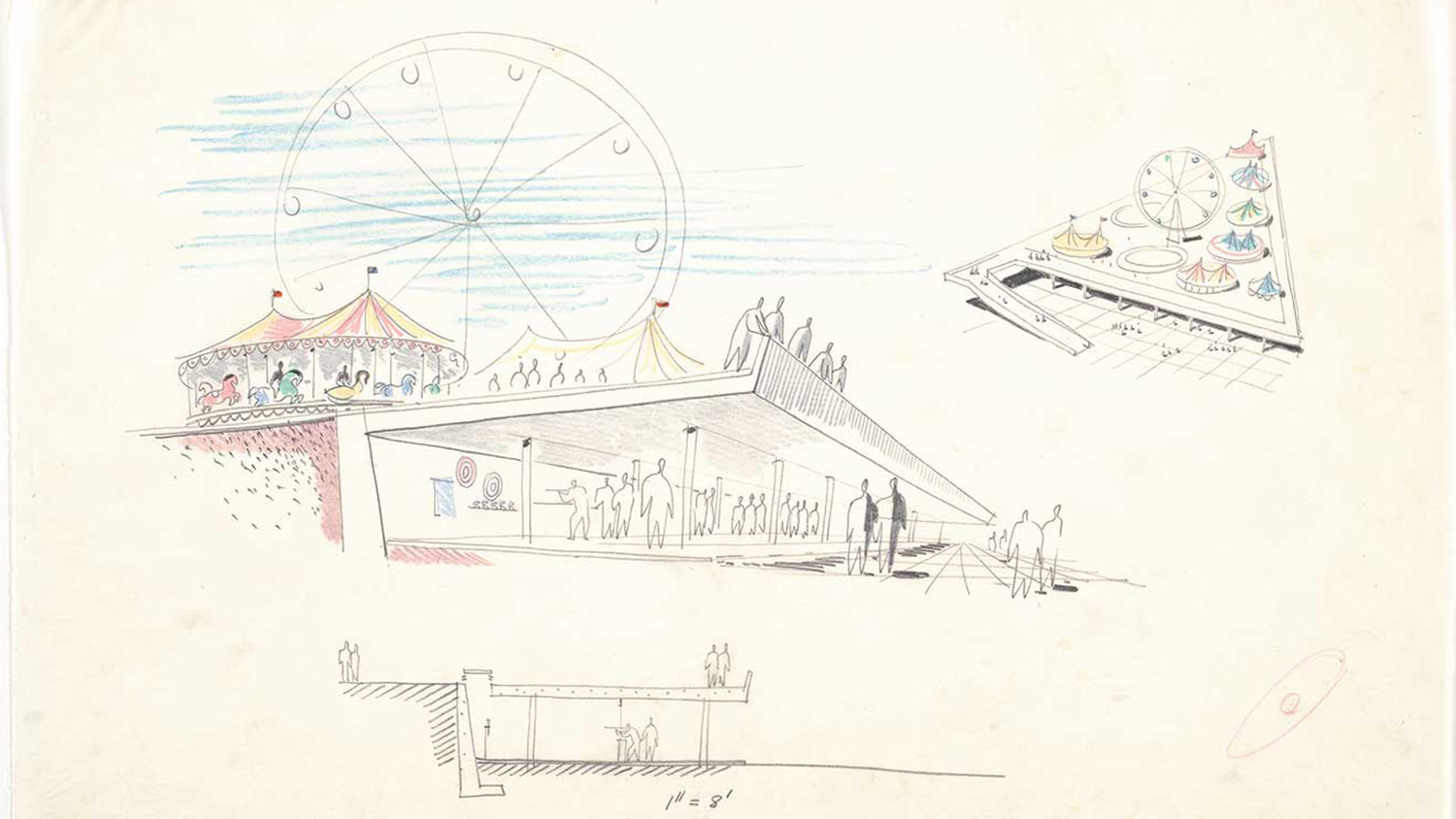

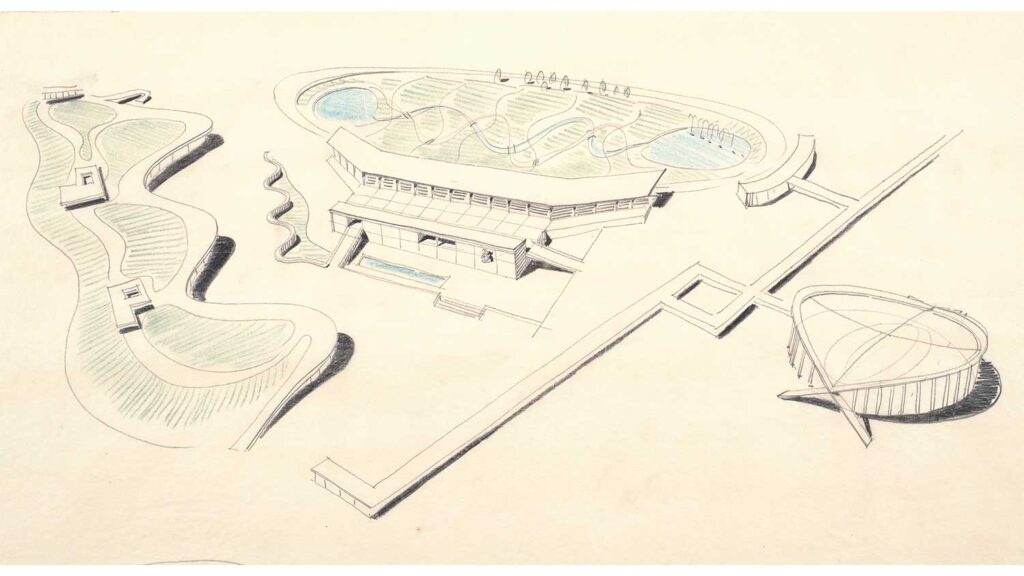

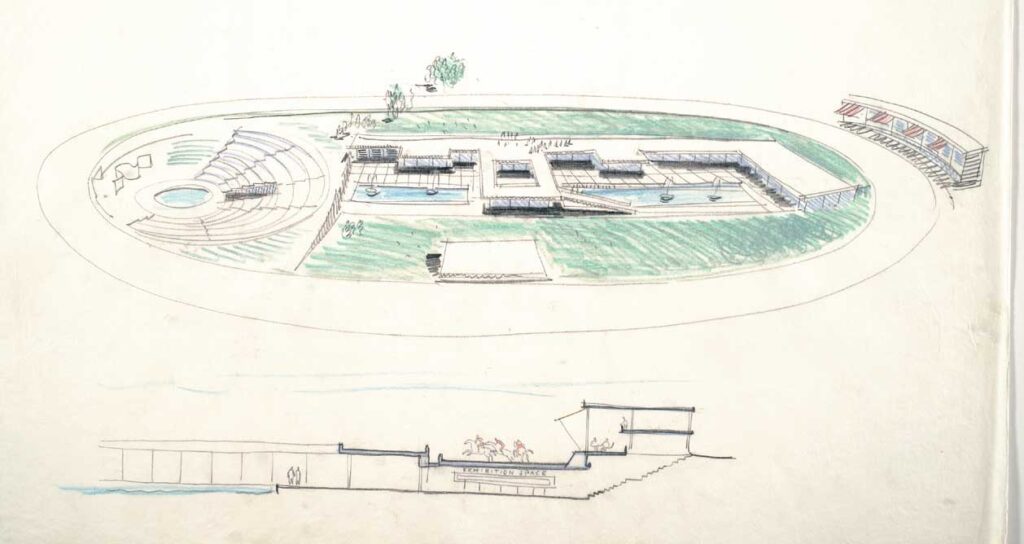

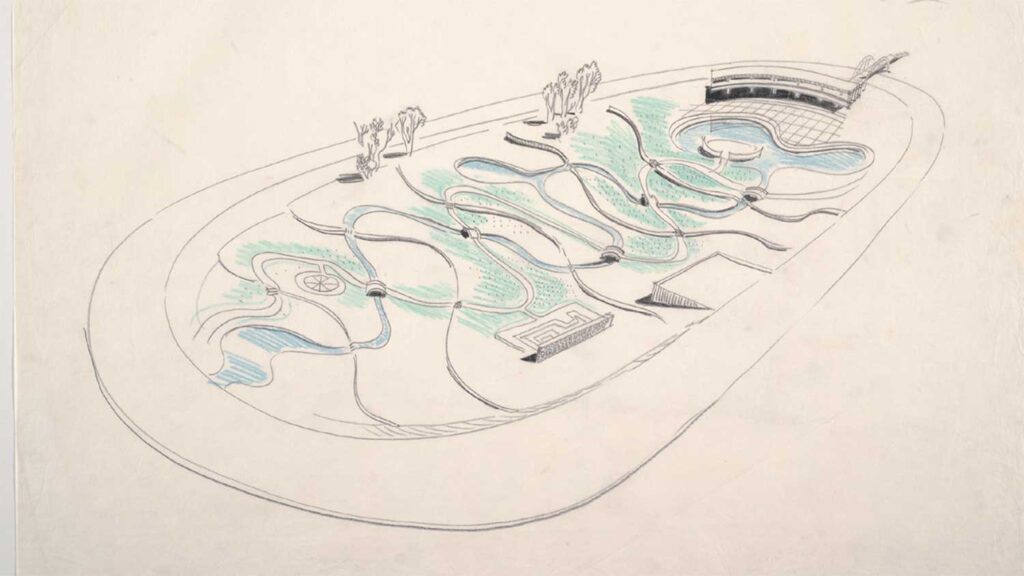

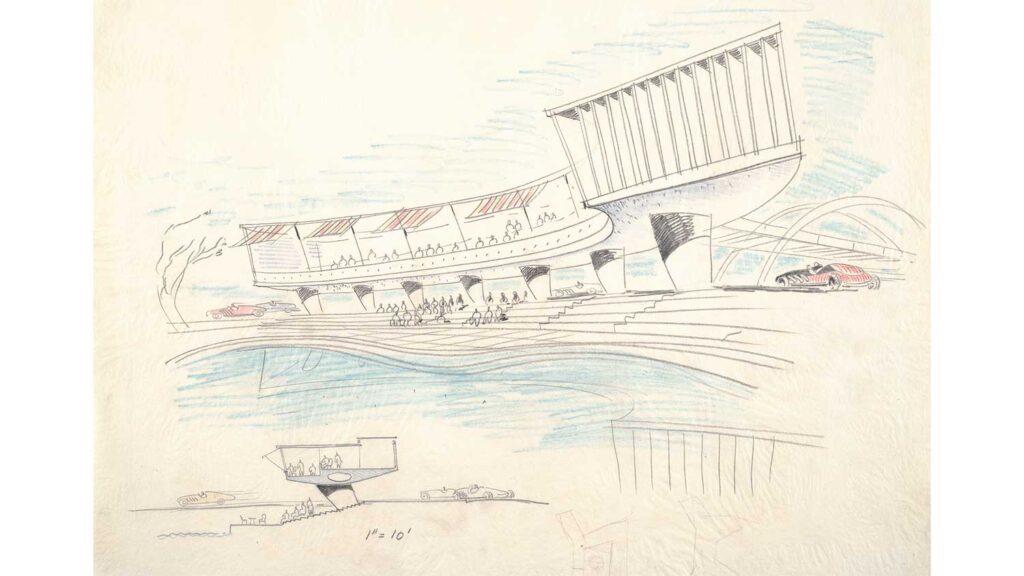

The pencil must have danced across the paper. In one drawing, a whirling merry-go-round sits atop an elevated midway. On another page, streams and paths crisscross a park that forms the center of an oval track. A yellow sports car races in front of a grandstand held up by giant curved pillars.

Those are visions of the North Carolina State Fair, circa 1950 — a state fair that, in fact, never was. The drawings, more than 50 in all, exemplify what remains of the imagination of Matthew Nowicki, the NC State architecture professor who designed Dorton Arena — and then died in a plane crash before it was built and before many of his ideas could be realized.

The drawings on sheets of tracing paper are archived in NCSU Libraries’ Special Collections at D.H. Hill Library, where scholars from all over the country come to see them. “They are remarkable,” says David Hill ’96, ’97, an NC State associate professor of architecture who has taken his students to see the collection. “They are incredibly drawn. There is such a sense of perspective; you get a sense of the entire landscape. The buildings are fantastic.”

The drawings offer more than a glimpse into Nowicki’s genius. They also tell the story of the extraordinarily talented architects who helped launch the School of Design in the late 1940s, and the unexpected vision of a fair manager named J. Sibley Dorton.

Dorton, who hailed from Shelby, N.C., became manager of the fair in 1937, and by 1948 he was ready to make changes. The fair had been shut down from 1942–45 because of World War II, and Dorton dreamed of fairgrounds with buildings that could be used year-round. “There was a determination to modernize North Carolina, a postwar excitement, to get this state out of the mud, to be progressive and up-to-date,” says Catherine Bishir, an architectural historian and curator of the architecture special collections at D.H. Hill. “The State Fair became a focus of that opportunity.’’

“There was a determination to modernize North Carolina, a postwar excitement to get this state out of the mud, to be progressive and up-to-date. The State Fair became a focus of that opportunity.”

— Catherine Bishir, an architectural historian and curator of the architecture special collections at D.H. Hill

At the time, Dean Henry Kamphoefner had assembled an amazing array of modernist architects for the faculty at State College’s new School of Design, which opened in 1948. Among them was Nowicki (pronounced no-VISK-ee). Born in Russia, Nowicki was the son of a well-to-do Polish family. He studied architecture at Warsaw Polytechnic Institute and quickly established himself as a talented architect, taking on projects in Warsaw and designing Poland’s pavilion for the 1939 World’s Fair. He came to the United States to help design the United Nations building in New York. On the recommendation of New Yorker magazine architecture critic Lewis Mumford, Kamphoefner asked Nowicki to chair the school’s architecture department. It was a group known for innovation.

It was only natural that Dorton, the man in charge of modernizing the fair, would turn to the design school for help with his plans, which included a livestock exhibition hall. Kamphoefner sent Dorton to Nowicki and another NC State architecture professor, George Matsumoto. When the two first met with Dorton, they brought preliminary drawings for an exhibition hall—but weren’t expecting that the fair manager would be open to anything particularly exciting.

They were wrong. As Dorton began to speak, the professors realized that they had underestimated him. “He sat there and outlined what he envisioned. . .and it was in grandiose terms,” Matsumoto said in a 2009 interview with Hill, the NC State professor. “Oh, good God, it was big. Nothing compared to what we had sketched out.” So the two got together during a break and decided not to show any of the drawings they had brought. “They realized they shot low, which is unusual for an architect,” Hill says.

What emerged from that initial meeting were Nowicki’s plans for what would become Dorton Arena. The design was revolutionary — a saddle-shaped building, with two sloping parabolic arches intersecting near the ground and a roof supported by cables running from arch to arch. It was the first building in the world with a cable-suspended roof, a design that allowed for an unobstructed view from any seat because there was no need for structural supports. Upon completion in 1952, the building, first called the Livestock Judging Pavilion, became an international sensation in architectural circles. “People came to see it from all over the world,” says Bishir. “It was considered a wonder of architecture.” Five years after it was built, the American Institute of Architects named it one of the 10 buildings constructed in the 20th century most expected to influence the future of American architecture. A few years later, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

But Nowicki did not live to see it.

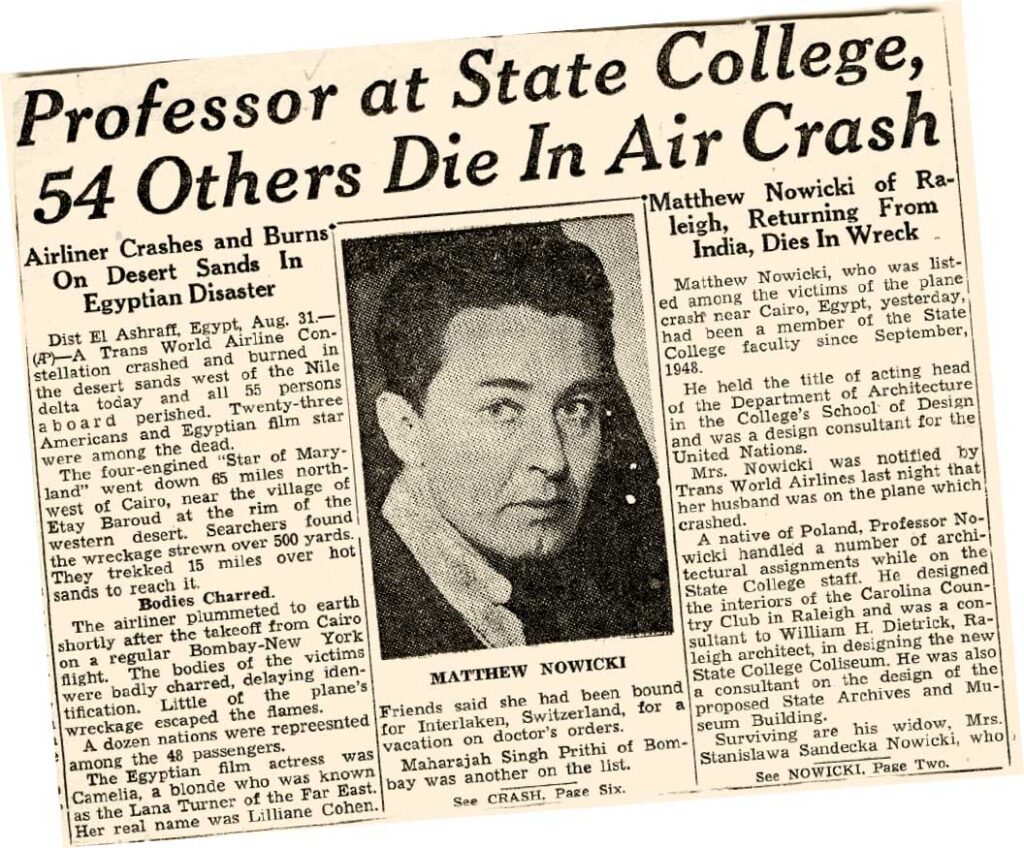

In 1950, he received a new commission, and this one was an architect’s dream: design the city of Chandigarh, the capital of the new province of Punjab in India. The News & Observer wrote a story before he left on a six-week trip to India in June of that year, noting that Nowicki’s wife, Sasha, and two young sons would stay behind. The next time Nowicki’s name appeared in the paper it was front-page news: “Professor at State College Among 55 Air Crash Victims.” On Aug. 30, TWA Flight 903 from Cairo — the second leg of Nowicki’s flight to New York—lost an engine and crashed during an emergency landing in the Sahara Desert.

“If time had allowed his genius to spread his wings in full, this poet-philosopher of form would have influenced the whole course of architecture.”

—Architectural Forum

Architectural historians have written that much of Nowicki’s legacy lies not in the buildings he left behind but in his lost potential to alter the history of modern architecture. In Architectural Forum magazine, his obituary said that “if time had allowed his genius to spread his wings in full, this poet-philosopher of form would have influenced the whole course of architecture.”

And the State Fair plans? It’s not clear whether Nowicki presented his other ideas — a modernist grandstand, an elevated midway — to Dorton. “Whether [Nowicki] was just thinking through ideas or planned to use these to communicate with the potential client, we don’t know,” Bishir says.

The dozens of State Fair drawings, along with plans for Chandigarh and a proposal for a new science and history museum in Raleigh, remain in table-sized flat folders, the pencil strokes nothing more than a promise.

- Categories: