The Greatest Ever?

We look back to our 2012 feature on Jack McDowall ’28, a four-sport star for the Wolfpack. He made his most lasting mark leading the 1927 football team to its first Southern Conference championship.

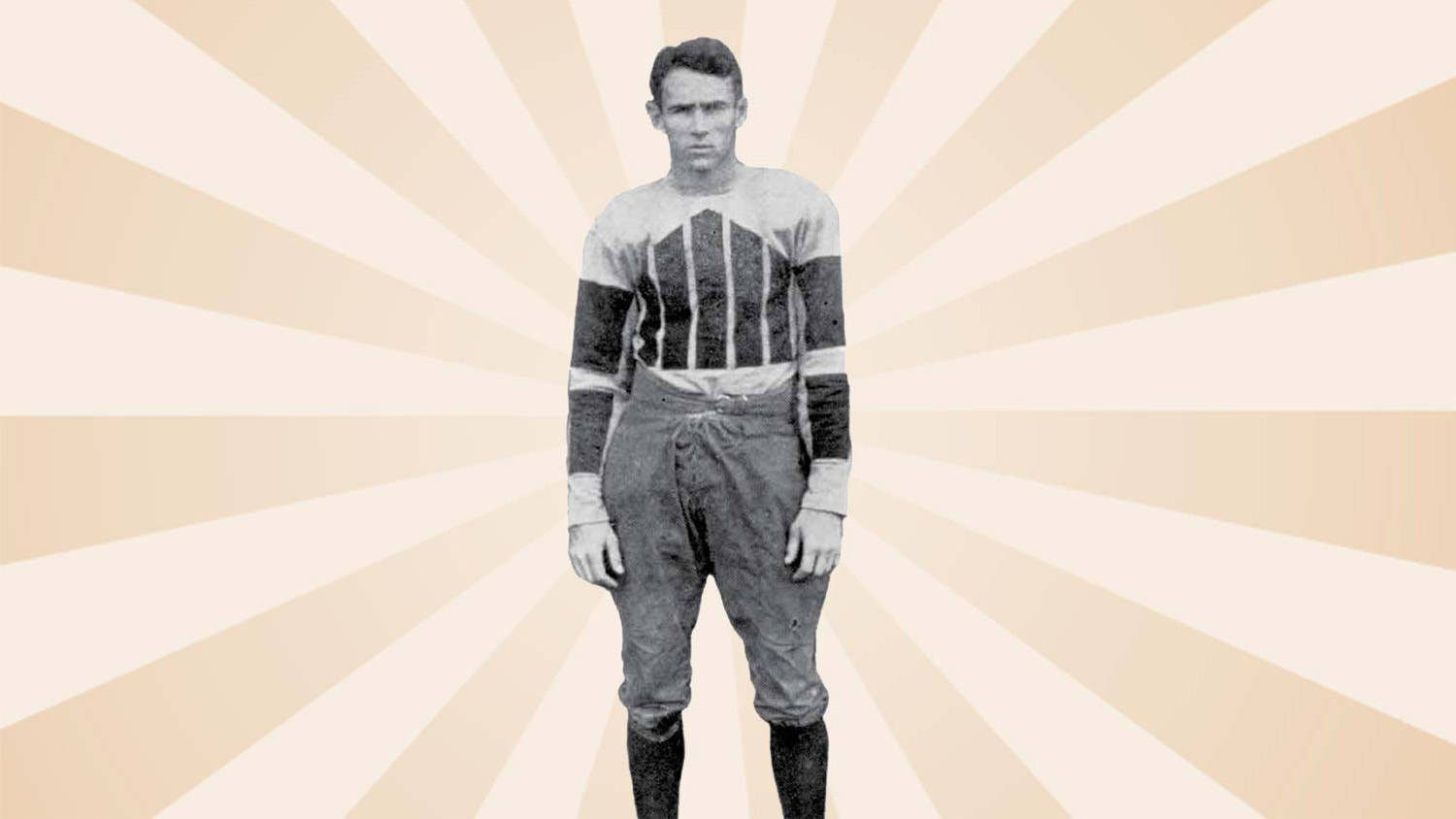

No one would have mistaken Jack McDowall for a football star when he showed up as a freshman at the North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Engineering in 1924. He was tall and skinny, weighing no more than 160 pounds, and wore thick glasses to help with poor eyesight. One observer jokingly described him as “4F,” a familiar Selective Service designation in the years after World War I that indicated someone was not physically or mentally fit to serve in the military. He was a face in the crowd, one of 1,200 students at State College. None of them saw the young man from Rockingham, N.C. (and before that, Gainesville, Fla.) as the football hero that State College was desperately seeking.

Soon enough they would realize, though, that they had found their hero. But even in their wildest dreams, State College students and fans could not have imagined how good McDowall would be on the football field—or on the basketball court, the baseball field and in track and field, for that matter. Time and again, McDowall’s passing, running, tackling and kicking led Wolfpack football teams to victory, including their first win over UNC-Chapel Hill in years and their first Southern Conference championship, in 1927. Sports writers struggled to find new superlatives to describe McDowall’s play, which seemed to reach new heights with each game.

By the time his college days were over in 1928, McDowall was widely acclaimed as the best athlete to ever play for State College. Some might argue that he still is.

State Struggles to Keep Up

College football was experiencing something of a heyday in the 1920s, led by the likes of Knute Rockne and his powerful offense at Notre Dame and the excitement that surrounded the annual Army-Navy game. The war was over, and fans welcomed the diversion that sports offered. Reforms in the early part of the century, led in part by President Theodore Roosevelt, had saved college football from itself by making the game safer after 22 players had died during the 1905 season. “Football weekends epitomized undergraduate social life, as raccoon coats replaced buckskins as the clothing of adventuresome youth,” Bill Beezley wrote in his 1976 book, The Wolfpack . . . Intercollegiate Athletics at North Carolina State University. “The radio brought games to those thousands whose crystal sets served as a key to the fraternity of football fans.”

At State College, though, the football program had struggled to find consistent success since a handful of students (and, apparently, a few nonstudents) had formed a football team and used their own money to travel to Oxford, N.C., in 1890 to earn the college’s first athletic victory against a prep school called Horner Academy. State College’s athletic teams had been hampered more than those at other schools during the war when the Department of the Army decided that students in its officer training programs — at places like State College — could not participate in college athletics. The Navy, which had training units at UNC-Chapel Hill, allowed its men to continue to play college sports. But the football woes at State College continued after the war was over, prompting the college to bring in a consultant from the Carnegie Institute to suggest areas for improvement. Those recommendations called for the creation of a Department of Physical Education that would provide some institutional oversight for intercollegiate athletics while ensuring that all students received physical training.

As football season approached in 1925, expectations were not high. State College had lost more than half of its 17 lettermen from the previous year, and new head coach Gus Tebell was not sure what his starting lineup would look like. Athletics Director J.F. Miller had implored students to try out for the football team if they had any experience or “a physical make-up.” “Every Freshman should enter college with one idea in mind, that is, to do anything and everything in his power to represent State College in her competition with other colleges,” Miller wrote in the Technician.

That’s McDowall, With an “A”

McDowall had played well the year before for the freshman team, which won two of its four games. But he was barely mentioned in preseason stories about the varsity team. When his name was mentioned, it was often misspelled as “McDowell,” with an “e” instead of an “a.” It was a mistake that would occur throughout his playing days. (And later, for that matter. He was incorrectly listed as “Jack McDowell” for years at the N.C. Sports Hall of Fame.)

McDowall gave his coaches little indication of his potential before the season started, rarely working hard during practices.

It didn’t take long, though, for McDowall to give the team’s fans (and his coaches) something to cheer about. The Wolfpack won its season opener against Richmond 20-0, and McDowall was an immediate sensation as a halfback who could run, pass and — in a time before specialists — kick the tar out of the ball. Substitutions were rare, with players typically playing on offense and defense. “McDowall, the fast-stepping half from Rockingham, was the star of the game,” read an account of the Richmond game. “His work of passing, punting and running was brilliant. His longest run of the game for 75 yards was made only after he had sidestepped and dodged many of his would-be tacklers.” Despite his lean frame, McDowall was also one of the hardest tacklers on the defense and had a powerful throwing arm. One of his coaches surmised that McDowall must have had wire in his muscles.

State College fans, desperate for football success, wasted no time in speculating about what the team might be able to do with a star like McDowall. A limerick in the school newspaper even raised the possibility of “championship aims” for the long-suffering football team.

But McDowall missed the second game of the season after being treated for blood poisoning in his right arm caused by scratches and bruises he had suffered during the game against Richmond. The rest of the season brought the sorts of highs and lows that were familiar to State College fans. Led by McDowall, the team beat Duke and Wake Forest. But State College lost to teams from VMI, Davidson, Washington and Lee and, yet again, UNC-Chapel Hill. When the Faculty Athletic Committee met on Nov. 3, 1925, the last item on the agenda was the “Morale of the Football Team.” Later that month, Miller, the athletics director, issued a statement to the student body, encouraging them to form a booster club and root for the school’s athletics teams.

A Star in Other Sports

With football season over, McDowall turned to other sports. He quickly became a starter on the basketball team, known then as the Red Terrors, as a guard who was noted more for his ball-handling and defense than for his scoring. But when State College played Duke in January 1926, McDowall demonstrated his knack for making big plays in big moments, be it on the football field or the basketball court. Duke was leading by one point late in the game at Frank Thompson Gymnasium when McDowall grabbed the ball at one end of the floor, dribbled to the center of the court and, with seconds to play, launched a shot that went “squarely” through the basket and won the game for State College. “The whistle blew while the ball was in the air and the most exciting game of the season was at an end,” read the account in the Technician.

McDowall, who also played baseball and was a member of the track team, was one of three finalists his sophomore year for the Norris Athletic Trophy, an award given annually to the best athlete at State College. But before students got a chance to vote on who should receive the award, McDowall withdrew his name from consideration. He asked that students instead vote for two brothers, both seniors, who were on the football and baseball teams. Meanwhile, McDowall’s athletic accomplishments continued to pile up. The next month, McDowall “smashed” the Southern Conference record in the high jump and finished second in the broad jump. He was the second leading point earner for the track team that year, and one of only two State College athletes to compete in that year’s Southern Conference track-and-field meet.

Seeking Football Success

In 1926, McDowall’s junior year, the football team continued to struggle. McDowall performed well, switching at times to quarterback and right end because of injuries to other players or Tebell’s efforts to generate some offense. A 7-3 loss to Clemson was typical of the games that season. “He played a very brilliant game throughout,” a writer said of McDowall, “and gained the admiration of the small crowd which witnessed the game. Jack tried in vain to complete passes, but State ends failed to hold them.” When State College played UNC-Chapel Hill, McDowall missed most of the game due to an injury and UNC-Chapel Hill notched another win in the rivalry.

But McDowall gave fans reason to hope before the season was over. He ran for two touchdowns, threw for another touchdown and kicked two extra points in a 26-19 win over Duke. One of the touchdown runs stood out, even by McDowall’s standards. “In the second quarter he received a Duke punt on the 5-yard line and, by stiff-arming, brokenfield running, and good interference, he staggered almost exhausted across the goal line for a touchdown,” read the account in the Technician. McDowall would later describe the 1925 and 1926 teams, which had gone 3-5-1 and 4-6, respectively, as “two of the worst football teams ever heard of.” But no one held McDowall accountable for the poor showings. Following another season as a starter on the basketball team, and splitting his time between the track team and the baseball team, McDowall won the Norris trophy his junior year as the best athlete at State College. But the best was still to come.

A Senior Year to Remember

As the 1927 football season approached, expectations among State College fans were uncharacteristically high. Not only was McDowall back for his senior season, but Tebell had several other promising players on the team. “We’ve really got a team that can’t be stopped,” read a story in the student newspaper. That certainly appeared to be the case in the season opener, in which State College defeated Elon 39-0. That was followed, though, by a disheartening 20-0 loss to Furman. Then McDowall took over, leading his team to an 18-6 victory over Clemson and a decisive 30-7 win over Wake Forest, which a newspaper headline declared as the “best game of his college career.”

Never before has State College seen her favorite athlete strut her stuff in such a manner. He can do anything, from run to tackle. His forward passes are brilliant. His punts are marvelous. His running is of such a caliber that the opposition almost break their backs trying to stop him.

The team’s fans could barely contain themselves. “Jack McDowall was in his prime,” wrote one sports columnist. “Never before has State College seen her favorite athlete strut her stuff in such a manner. He can do anything, from run to tackle. His forward passes are brilliant. His punts are marvelous. His running is of such a caliber that the opposition almost break their backs trying to stop him.” A columnist for the Technician suggested that the team should win the so-called state championship, the informal honor given to the college team in North Carolina with the best record. “Students, this is our golden opportunity,” read the column.

Up next was one of the toughest games on the Wolfpack schedule — the University of Florida, a traditional football powerhouse. It would be the first time the two schools had met in any athletic contest, and fans were alternately excited by the opportunity and nervous about the possible outcome. For McDowall, the game had special meaning. He had been a high school football star in Gainesville, Fla. — home of the University of Florida — before moving to Rockingham, N.C., for his final year of high school. But the coaches at the University of Florida had not been interested in McDowall, saying he was too small for their team. This was his chance to show them they had made a mistake.

The game, played in Tampa, started slow. Neither team scored until the fourth quarter, when a long pass from McDowall took the Wolfpack to the 3-yard line. State College ran the ball three straight times, but each time the Florida defense stopped them short of the goal line. On fourth down, McDowall threw a short pass for a touchdown, putting State College ahead 6-0. But, as a Florida sports writer noted, McDowall was not done. With Florida scrambling to score a touchdown, McDowall intercepted a pass and took off on “a breath-taking, eye-twisting dash of 75 yards.” State College won 12-6, giving McDowall his win over Florida. His teammates gave him the game ball for his efforts. “After a few days, I wrapped up the ball in a neat package and mailed it to the athletic director at Florida as a souvenir,” McDowall recalled years later.

A Couple of Championships

State College was 4-1, and the University of North Carolina was next on the schedule. The Wolfpack had not beaten their rival since 1921, so fans were desperate for a victory. More than 12,000 of them packed Riddick Stadium for the Saturday game, and State College started strong, relying on McDowall’s passing and running to build a 13-0 lead at halftime. UNC was the aggressor in the second half, but State’s defense managed to hold Carolina scoreless in the third quarter. North Carolina finally scored a touchdown in the fourth quarter, but McDowall sealed the victory when he took the ball on the 5-yard line, started to run to the right and then pulled up and threw a pass to an end standing alone in the end zone. The final score was 19-6. Again, McDowall was credited with leading the team to victory, with one sports writer declaring simply, “It was McDowall Day.”

NC State easily defeated Davidson, 25-6, setting up a game against Duke to decide the so-called state championship that had eluded State College for nine years. More than 11,000 fans, including members of the UNC-Chapel Hill football team, packed Duke’s Haynes Field. “It will be a fight,” predicted Tal Stafford, the athletics director for State College. “Duke will know they will have been in a game.”

State College fell behind 12-0, but came back to win when McDowall “put up a dramatic exhibition of brilliance unrivaled anywhere on the nation’s gridirons this season,” according to one account. McDowall threw for three touchdowns, had several long runs (“In an open field, you couldn’t hit him with a handful of grits,” read one account of McDowall’s feats.) and kicked one punt an astounding 73 yards. The Wolfpack left Durham with a 20-18 victory in what McDowall later said was his greatest day playing for State College.

With the state championship in place, State College still had a shot at its first Southern Conference crown. The team was 7-1 and undefeated in conference play (Furman was not part of the conference), with one conference game remaining against South Carolina, which had beaten State College the last three years. The game was to be played on Thanksgiving Day in Columbia, S.C.

The Wolfpack rose to the occasion, winning 34-0. McDowall played his usual stellar game, leading the way with several long passes that “demoralized” the South Carolina team. State College had one more game on the schedule, against Michigan State, but it had finished its conference schedule undefeated. Two other Southern Conference teams also finished undefeated, and the three teams shared the conference title. State College would go on to defeat Michigan State 19-0, ending the most successful season in the history of State College to that point.

McDowall, who played all but six minutes in the football team’s 10 games, went on to start for the basketball and baseball teams and be one of the stars on the track team, earning 11 letters during his years at State College. (Years later, McDowall would bemoan not playing baseball his sophomore year so he could have earned a 12th letter.) State College students awarded him the Norris trophy again in his senior year. McDowall, pictured wearing a State letter sweater and glasses, was featured in the 1928 Agromeck as the best athlete and most popular member of the senior class.

Recalling His Greatness

After graduating with a degree in business, McDowall took a job as an English teacher and coach at Asheville (N.C.) High School. After a year, he returned to Florida as a coach at Rollins College near Orlando. He would work there for 29 years, as a football, basketball and baseball coach, as well as athletics director. In retirement, McDowall was an avid fisherman and golfer who frequently shot in the 70s. In 1975, six years after his death from an apparent heart attack, McDowall was the first player at NC State to be enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Ind. He is still one of only six NC State players in the Hall of Fame (which is now in Atlanta, Ga.,) the others being Roman Gabriel ’63, Jim Ritcher ’86, Dennis Byrd ’69, Ted Brown ’79 and Torry Holt ’99. Former NC State football coach Dick Sheridan was enshrined in 2020.

But McDowall is not a familiar name to many of today’s State fans, a victim perhaps of playing in a time before television and multi-million dollar contracts for professional athletes. There is no trophy or scholarship in his honor at NC State, and he was not among the 10 athletes, all from the modern era, who were named to the inaugural class of the NC State Athletics Hall of Fame. (He was inducted two years later, in 2014.) McDowall’s story is found instead in old newspaper clippings and the words of his coaches and teammates.

Butch Slaughter, an assistant coach on the 1927 team, said years later that McDowall was one of the greatest athletes he ever saw. “He was a guy who did something to win for you no matter what — run, pass, kick or tackle,” he said. “He could do anything, either the orthodox way or the unorthodox. He was half blind but could shoot the basketball. He could hit a baseball a mile. And he held the Southern Conference high jump record for years, using the old-fashion scissors kick. He didn’t have any form; he just ran up to the bar and jumped over it.”

When McDowall was posthumously inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame, his teammates recalled some of McDowall’s athletic heroics at State College. Quarterback C.A. “Peanut” Ridenhour ’28 said McDowall had confidence in his athletic abilities, even if he didn’t look like an athlete. “If we have a baseball game and a track meet at the same time, he would leave the ball field, run over to the meet, dressed in his baseball uniform, jump twice, then run back to the baseball field. And he’d tell us at the track, ‘If anybody beats that, call me and I’ll come back and jump again.’ ”

George Hunsucker ’29, a halfback on the 1927 team, said McDowall was able to do whatever was necessary to lead the Wolfpack to a victory. “He might practice five minutes a day, but when it came time to play, he was ready,” Hunsucker recalled. Then Hunsucker shook his head as he tried to convey to a reporter how great McDowall had been.

“You know,” he said, “people today just wouldn’t believe the things he could do.”

Editor’s note: Sources for this story included old newspaper clippings—primarily from the Technician, The News & Observer and The Raleigh Times — and letters, meeting transcripts, programs, photos and other documents archived at D.H. Hill Library and in the files of the Department of Athletics and the NC State Alumni Association. Other valuable sources were The Wolfpack . . . Intercollegiate Athletics at North Carolina State University, by Bill Beezley, a former history professor at NC State, and the Agromeck. The College Football Hall of Fame and the N.C. Sports Hall of Fame also provided documents and photos.

- Categories: